SOME HISTORICAL DATA.

19

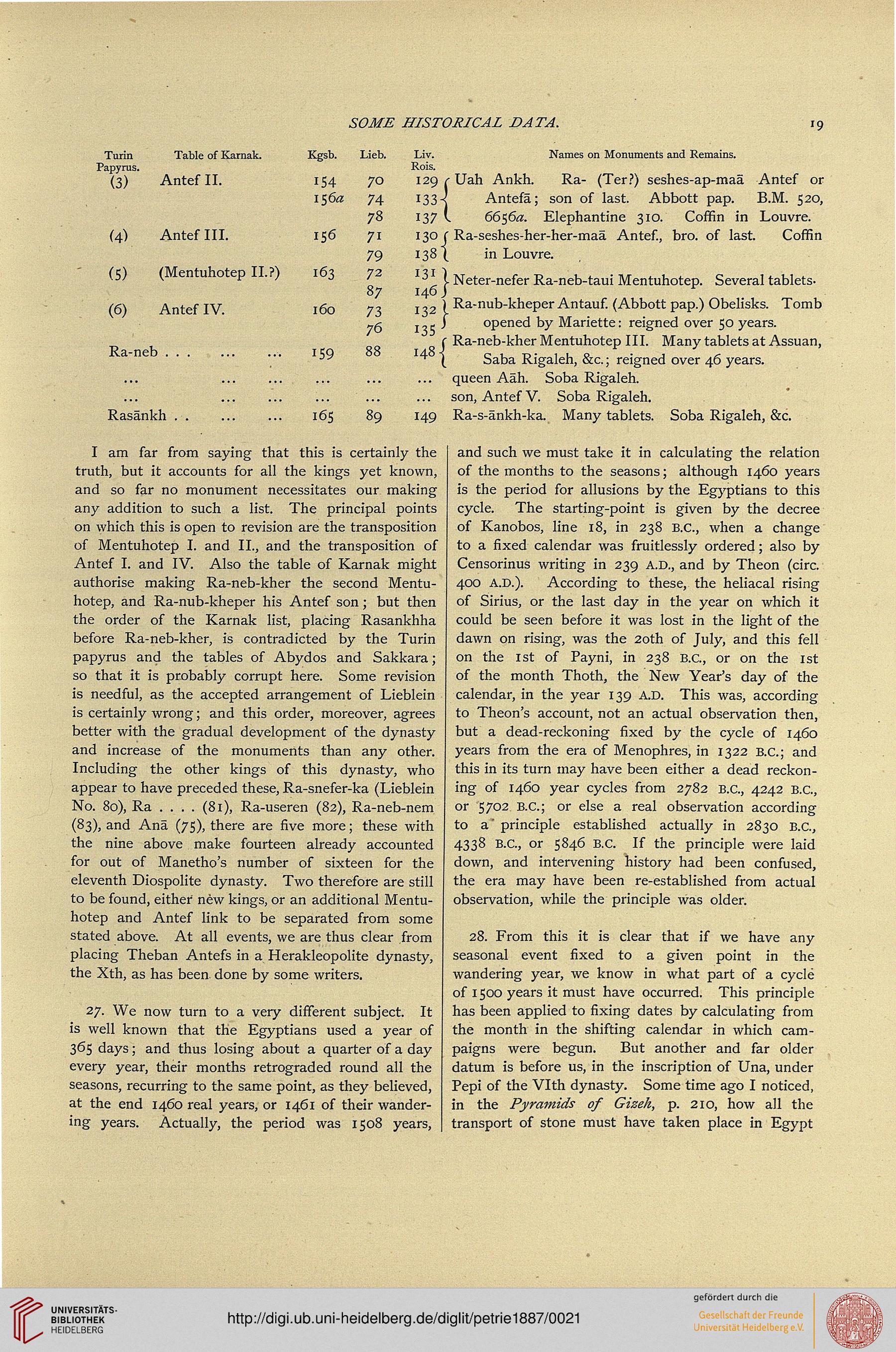

Turin Table of Karnak.

Papyrus.

(3) Antef II.

(4) Antef III.

(5) (Mentuhotep II.?)

(6) Antef IV.

Ra-neb . . .

Rasankh

Kgsb.

iS4

156

163

160

159

Lieb.

70

74

78

7i

79

72

87

73

76

88

Names on Monuments and Remains.

I6S 89

Liv.

Rois.

129 r Uah Ankh. Ra- (Ter?) seshes-ap-maa Antef or

133-J Antefa; son of last. Abbott pap. B.M. 520,

137 I 6656a. Elephantine 310. Coffin in Louvre.

130 f Ra-seshes-her-her-maa Antef., bro. of last. Coffin

138 ( in Louvre.

■* I- Neter-nefer Ra-neb-taui Mentuhotep. Several tablets-

146 J

j ,2 ) Ra-nub-kheper Antauf. (Abbott pap.) Obelisks. Tomb

j - j opened by Mariette: reigned over 50 years.

c Ra-neb-kher Mentuhotep III. Many tablets at Assuan,

4 \ Saba Rigaleh, &c.; reigned over 46 years.

queen Aah. Soba Rigaleh.

son, Antef V. Soba Rigaleh.

149 Ra-s-ankh-ka. Many tablets. Soba Rigaleh, &c.

I am far from saying that this is certainly the

truth, but it accounts for all the kings yet known,

and so far no monument necessitates our making

any addition to such a list. The principal points

on which this is open to revision are the transposition

of Mentuhotep I. and II., and the transposition of

Antef I. and IV. Also the table of Karnak might

authorise making Ra-neb-kher the second Mentu-

hotep, and Ra-nub-kheper his Antef son; but then

the order of the Karnak list, placing Rasankhha

before Ra-neb-kher, is contradicted by the Turin

papyrus and the tables of Abydos and Sakkara;

so that it is probably corrupt here. Some revision

is needful, as the accepted arrangement of Lieblein

is certainly wrong; and this order, moreover, agrees

better with the gradual development of the dynasty

and increase of the monuments than any other.

Including the other kings of this dynasty, who

appear to have preceded these, Ra-snefer-ka (Lieblein

No. 80), Ra .... (81), Ra-useren (82), Ra-neb-nem

(83), and Ana (75), there are five more; these with

the nine above make fourteen already accounted

for out of Manetho's number of sixteen for the

eleventh Diospolite dynasty. Two therefore are still

to be found, either new kings, or an additional Mentu-

hotep and Antef link to be separated from some

stated above. At all events, we are thus clear from

placing Theban Antefs in a Herakleopolite dynasty,

the Xth, as has been, done by some writers.

27. We now turn to a very different subject. It

is well known that the Egyptians used a year of

365 days; and thus losing about a quarter of a day

every year, their months retrograded round all the

seasons, recurring to the same point, as they believed,

at the end 1460 real years, or 1461 of their wander-

ing years. Actually, the period was 1508 years,

and such we must take it in calculating the relation

of the months to the seasons; although 1460 years

is the period for allusions by the Egyptians to this

cycle. The starting-point is given by the decree

of Kanobos, line 18, in 238 B.C., when a change

to a fixed calendar was fruitlessly ordered; also by

Censorinus writing in 239 A.D., and by Theon (circ.

400 a.d.). According to these, the heliacal rising

of Sirius, or the last day in the year on which it

could be seen before it was lost in the light of the

dawn on rising, was the 20th of July, and this fell

on the 1st of Payni, in 238 B.C., or on the 1st

of the month Thoth, the New Year's day of the

calendar, in the year 139 A.D. This was, according

to Theon's account, not an actual observation then,

but a dead-reckoning fixed by the cycle of 1460

years from the era of Menophres, in 1322 B.C.; and

this in its turn may have been either a dead reckon-

ing of 1460 year cycles from 2782 B.C., 4242 B.C.,

or 57°2 B-c-j or else a real observation according

to a* principle established actually in 2830 B.C.,

4338 B.C., or 5846 B.C. If the principle were laid

down, and intervening history had been confused,

the era may have been re-established from actual

observation, while the principle was older.

28. From this it is clear that if we have any

seasonal event fixed to a given point in the

wandering year, we know in what part of a cycle

of 1500 years it must have occurred. This principle

has been applied to fixing dates by calculating from

the month in the shifting calendar in which cam-

paigns were begun. But another and far older

datum is before us, in the inscription of Una, under

Pepi of the Vlth dynasty. Some time ago I noticed,

in the Pyramids of Gizeh, p. 210, how all the

transport of stone must have taken place in Egypt

19

Turin Table of Karnak.

Papyrus.

(3) Antef II.

(4) Antef III.

(5) (Mentuhotep II.?)

(6) Antef IV.

Ra-neb . . .

Rasankh

Kgsb.

iS4

156

163

160

159

Lieb.

70

74

78

7i

79

72

87

73

76

88

Names on Monuments and Remains.

I6S 89

Liv.

Rois.

129 r Uah Ankh. Ra- (Ter?) seshes-ap-maa Antef or

133-J Antefa; son of last. Abbott pap. B.M. 520,

137 I 6656a. Elephantine 310. Coffin in Louvre.

130 f Ra-seshes-her-her-maa Antef., bro. of last. Coffin

138 ( in Louvre.

■* I- Neter-nefer Ra-neb-taui Mentuhotep. Several tablets-

146 J

j ,2 ) Ra-nub-kheper Antauf. (Abbott pap.) Obelisks. Tomb

j - j opened by Mariette: reigned over 50 years.

c Ra-neb-kher Mentuhotep III. Many tablets at Assuan,

4 \ Saba Rigaleh, &c.; reigned over 46 years.

queen Aah. Soba Rigaleh.

son, Antef V. Soba Rigaleh.

149 Ra-s-ankh-ka. Many tablets. Soba Rigaleh, &c.

I am far from saying that this is certainly the

truth, but it accounts for all the kings yet known,

and so far no monument necessitates our making

any addition to such a list. The principal points

on which this is open to revision are the transposition

of Mentuhotep I. and II., and the transposition of

Antef I. and IV. Also the table of Karnak might

authorise making Ra-neb-kher the second Mentu-

hotep, and Ra-nub-kheper his Antef son; but then

the order of the Karnak list, placing Rasankhha

before Ra-neb-kher, is contradicted by the Turin

papyrus and the tables of Abydos and Sakkara;

so that it is probably corrupt here. Some revision

is needful, as the accepted arrangement of Lieblein

is certainly wrong; and this order, moreover, agrees

better with the gradual development of the dynasty

and increase of the monuments than any other.

Including the other kings of this dynasty, who

appear to have preceded these, Ra-snefer-ka (Lieblein

No. 80), Ra .... (81), Ra-useren (82), Ra-neb-nem

(83), and Ana (75), there are five more; these with

the nine above make fourteen already accounted

for out of Manetho's number of sixteen for the

eleventh Diospolite dynasty. Two therefore are still

to be found, either new kings, or an additional Mentu-

hotep and Antef link to be separated from some

stated above. At all events, we are thus clear from

placing Theban Antefs in a Herakleopolite dynasty,

the Xth, as has been, done by some writers.

27. We now turn to a very different subject. It

is well known that the Egyptians used a year of

365 days; and thus losing about a quarter of a day

every year, their months retrograded round all the

seasons, recurring to the same point, as they believed,

at the end 1460 real years, or 1461 of their wander-

ing years. Actually, the period was 1508 years,

and such we must take it in calculating the relation

of the months to the seasons; although 1460 years

is the period for allusions by the Egyptians to this

cycle. The starting-point is given by the decree

of Kanobos, line 18, in 238 B.C., when a change

to a fixed calendar was fruitlessly ordered; also by

Censorinus writing in 239 A.D., and by Theon (circ.

400 a.d.). According to these, the heliacal rising

of Sirius, or the last day in the year on which it

could be seen before it was lost in the light of the

dawn on rising, was the 20th of July, and this fell

on the 1st of Payni, in 238 B.C., or on the 1st

of the month Thoth, the New Year's day of the

calendar, in the year 139 A.D. This was, according

to Theon's account, not an actual observation then,

but a dead-reckoning fixed by the cycle of 1460

years from the era of Menophres, in 1322 B.C.; and

this in its turn may have been either a dead reckon-

ing of 1460 year cycles from 2782 B.C., 4242 B.C.,

or 57°2 B-c-j or else a real observation according

to a* principle established actually in 2830 B.C.,

4338 B.C., or 5846 B.C. If the principle were laid

down, and intervening history had been confused,

the era may have been re-established from actual

observation, while the principle was older.

28. From this it is clear that if we have any

seasonal event fixed to a given point in the

wandering year, we know in what part of a cycle

of 1500 years it must have occurred. This principle

has been applied to fixing dates by calculating from

the month in the shifting calendar in which cam-

paigns were begun. But another and far older

datum is before us, in the inscription of Una, under

Pepi of the Vlth dynasty. Some time ago I noticed,

in the Pyramids of Gizeh, p. 210, how all the

transport of stone must have taken place in Egypt