CORPUS RUBENIANUM PUAS'U.S' REMBRANDT RESEARCH PROJECT .

33

3. Rembrandt, №<? TW&Z? /Z/^owczyAf c. 1655, oil on canvas.

New York, The Frick Collection. Photo: Wikipedia

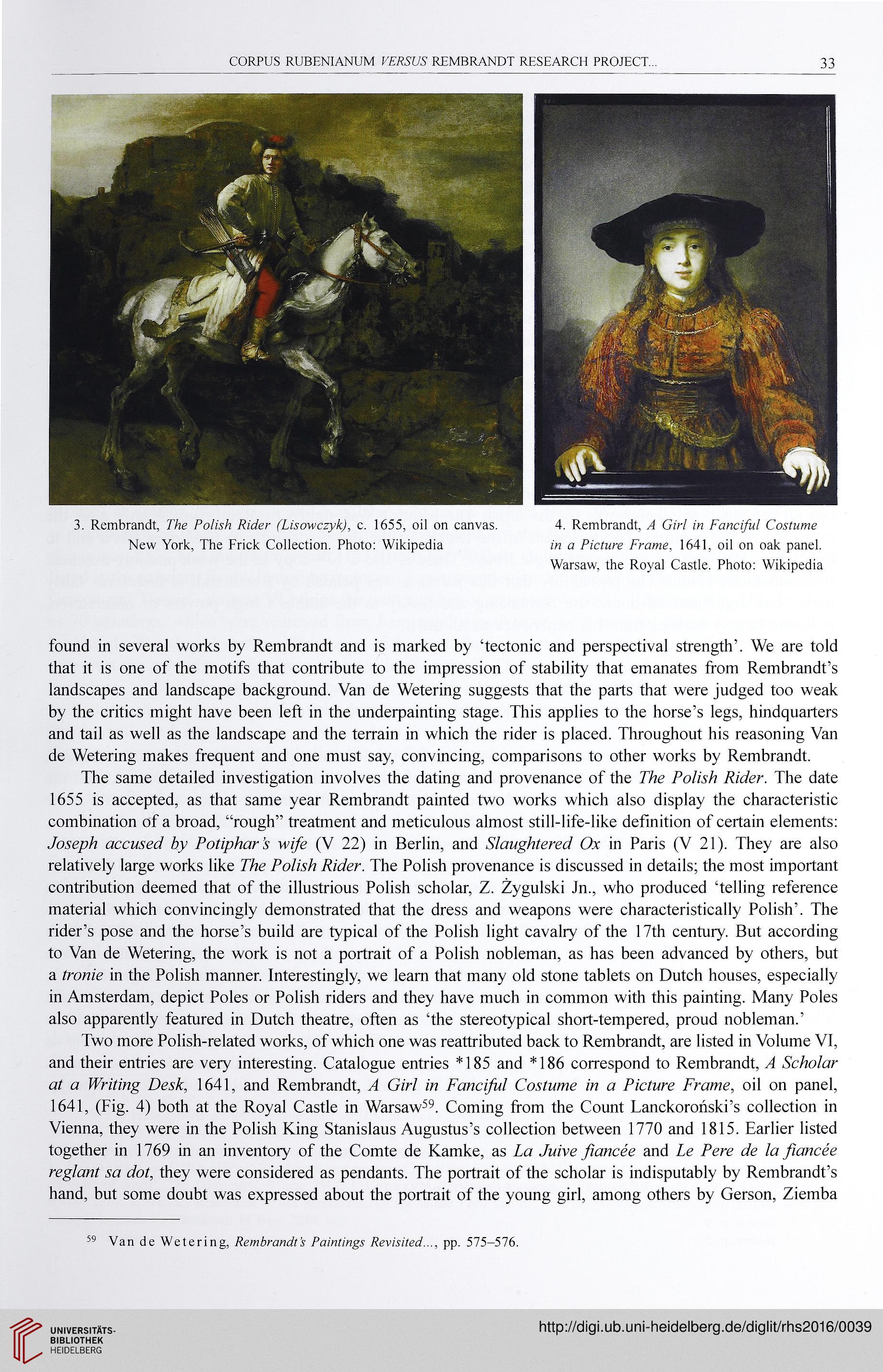

4. Rembrandt, И G;F/ m Танс//м/ Со^/мше

/n o Р/с/мге Tvowe, 1641, oil on oak panel.

Warsaw. the Royal Castle. Photo: Wikipedia

found in several works by Rembrandt and is marked by 'tectonic and perspectivai strength'. We are toid

that it is one of the motifs that contribute to the impression of stabiiity that emanates from Rembrandt's

landscapes and landscape background. Van de Wetering suggests that the parts that were judged too weak

by the critics might have been ieft in the underpainting stage. This apphes to the horse's iegs, hindquarters

and taii as weH as the iandscape and the terrain in which the rider is piaced. Throughout his reasoning Van

de Wetering makes frequent and one must say, convincing, comparisons to other works by Rembrandt.

The same detaiied investigation invoives the dating and provenance of the Ро/м/? Tù&r. The date

1655 is accepted, as that same year Rembrandt painted two works which aiso dispiay the characteristic

combination of a broad, "rough" treatment and meticuious almost stiii-iife-iike definition of certain eiements:

Толрр/? дссмлеб!' Ро?тр/?я?'У' w?/p (V 22) in Berlin, and 5)7cmg/??urg(7 Qv in Paris (V 21). They are aiso

reiatively iarge works iike 77?c Po/?ly/? D?<7c7*. The Poiish provenance is discussed in detaiis; the most important

contribution deemed that of the iilustrious Poiish schoiar, Z. Żygutski Jn., who produced 'teiling reference

materiai which convincingly demonstrated that the dress and weapons were characteristically Poiish'. The

rider's pose and the horse's build are typicai of the Poiish light cavalry of the i7th century. But according

to Van de Wetering, the work is not a portrait of a Polish nobleman, as has been advanced by others, but

a ?7w??e in the Polish manner. Interestingly, we ieam that many oid stone tabiets on Dutch houses, especiaiiy

in Amsterdam, depict Poles or Poiish riders and they have much in common with this painting. Many Poies

aiso apparentiy featured in Dutch theatre, often as 'the stereotypicai short-tempered, proud nobieman.'

Two more Polish-related works, of which one was reattributed back to Rembrandt, are iisted in Voiurne VI,

and their entries are very interesting. Cataiogue entries *185 and *186 correspond to Rembrandt, A &7?o/<2r

u? u HT??77?g Dc.sT. 1641, and Rembrandt, A G??7 ??? Са??с?/м/ Co.s?7??7?c /77 u R/c???^ C/'U77?c, oii on panei,

1641, (Fig. 4) both at the Royai Castie in Warsaw^. Coming from the Count Lanckorohski's coilection in

Vienna, they were in the Polish King Stanisiaus Augustus's coilection between 1770 and 1815. Eariier iisted

together in 1769 in an inventory of the Comte de Kamke, as 7o Л??Тс y?o?7ccc and 7c 7Ат-с <7c /o //owccc

rcg/<27?? <7o?, they were considered as pendants. The portrait of the schoiar is indisputabiy by Rembrandt's

hand, but some doubt was expressed about the portrait of the young giri, among others by Gerson, Ziemba

59 VandeWetering, Rew6ron<7?j Ro/n7/ngj RevA/?e<?..., pp. 575-576.

33

3. Rembrandt, №<? TW&Z? /Z/^owczyAf c. 1655, oil on canvas.

New York, The Frick Collection. Photo: Wikipedia

4. Rembrandt, И G;F/ m Танс//м/ Со^/мше

/n o Р/с/мге Tvowe, 1641, oil on oak panel.

Warsaw. the Royal Castle. Photo: Wikipedia

found in several works by Rembrandt and is marked by 'tectonic and perspectivai strength'. We are toid

that it is one of the motifs that contribute to the impression of stabiiity that emanates from Rembrandt's

landscapes and landscape background. Van de Wetering suggests that the parts that were judged too weak

by the critics might have been ieft in the underpainting stage. This apphes to the horse's iegs, hindquarters

and taii as weH as the iandscape and the terrain in which the rider is piaced. Throughout his reasoning Van

de Wetering makes frequent and one must say, convincing, comparisons to other works by Rembrandt.

The same detaiied investigation invoives the dating and provenance of the Ро/м/? Tù&r. The date

1655 is accepted, as that same year Rembrandt painted two works which aiso dispiay the characteristic

combination of a broad, "rough" treatment and meticuious almost stiii-iife-iike definition of certain eiements:

Толрр/? дссмлеб!' Ро?тр/?я?'У' w?/p (V 22) in Berlin, and 5)7cmg/??urg(7 Qv in Paris (V 21). They are aiso

reiatively iarge works iike 77?c Po/?ly/? D?<7c7*. The Poiish provenance is discussed in detaiis; the most important

contribution deemed that of the iilustrious Poiish schoiar, Z. Żygutski Jn., who produced 'teiling reference

materiai which convincingly demonstrated that the dress and weapons were characteristically Poiish'. The

rider's pose and the horse's build are typicai of the Poiish light cavalry of the i7th century. But according

to Van de Wetering, the work is not a portrait of a Polish nobleman, as has been advanced by others, but

a ?7w??e in the Polish manner. Interestingly, we ieam that many oid stone tabiets on Dutch houses, especiaiiy

in Amsterdam, depict Poles or Poiish riders and they have much in common with this painting. Many Poies

aiso apparentiy featured in Dutch theatre, often as 'the stereotypicai short-tempered, proud nobieman.'

Two more Polish-related works, of which one was reattributed back to Rembrandt, are iisted in Voiurne VI,

and their entries are very interesting. Cataiogue entries *185 and *186 correspond to Rembrandt, A &7?o/<2r

u? u HT??77?g Dc.sT. 1641, and Rembrandt, A G??7 ??? Са??с?/м/ Co.s?7??7?c /77 u R/c???^ C/'U77?c, oii on panei,

1641, (Fig. 4) both at the Royai Castie in Warsaw^. Coming from the Count Lanckorohski's coilection in

Vienna, they were in the Polish King Stanisiaus Augustus's coilection between 1770 and 1815. Eariier iisted

together in 1769 in an inventory of the Comte de Kamke, as 7o Л??Тс y?o?7ccc and 7c 7Ат-с <7c /o //owccc

rcg/<27?? <7o?, they were considered as pendants. The portrait of the schoiar is indisputabiy by Rembrandt's

hand, but some doubt was expressed about the portrait of the young giri, among others by Gerson, Ziemba

59 VandeWetering, Rew6ron<7?j Ro/n7/ngj RevA/?e<?..., pp. 575-576.