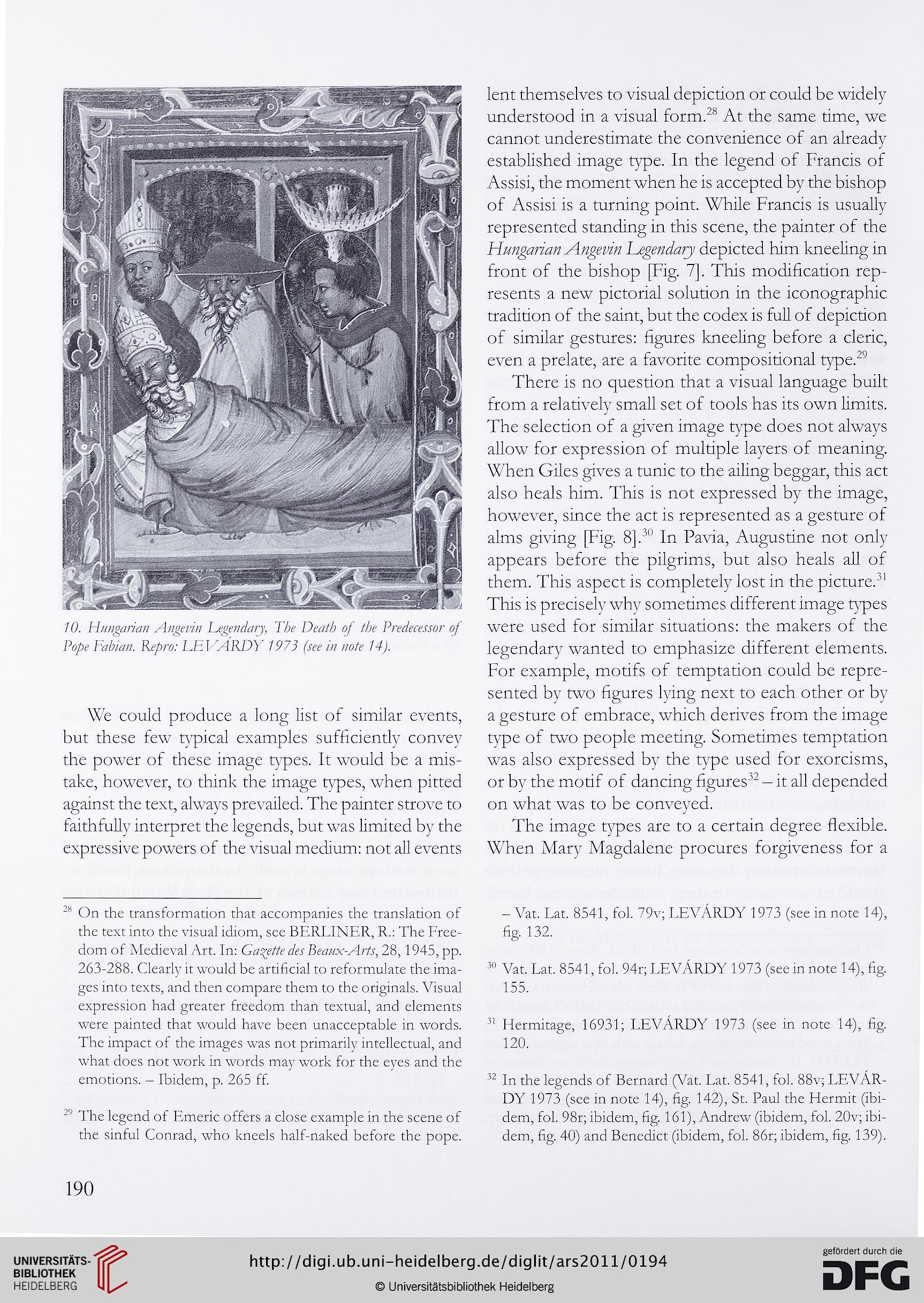

7 0. TA A 7^ř PrřArřrror A

Py)^ LhA^;t. Rřýw.' LELMRDV 7P73 přř 7// 74).

We could produce a long list of similar events,

but these few p^pical examples sufhciently convey

the power of these image types. It would be a mis-

take, however, to think the image prpes, when pitted

against the text, always prevailed. The pamter strove to

faithřully interpret the legends, but was limited by the

expressive powers of the visual medium: not all events

On the transformation that accompanies the translation of

the text into the visual idiom, see BERLINER, R.: The Free-

dom of Medieval Art. In: (DyíTň? Ar Př^vAbL, 28,1945, pp.

263-288. Clearly it would be artiňcial to reformulate the ima-

ges into texts, and then compare them to the Originals. Visual

expression had greater freedom than textual, and elements

were painted that would háve been unacceptable in words.

The impact of the images was not primarily intellectual, and

what does not work in words may work for the eyes and the

émotions. - Ibidem, p. 265 ff.

' " The legend of Emeric offers a close example in the scene of

the smful Conrad, who kneels half-naked before the pope.

lent themselves to visual depiction or could be widely

understood in a visual formA At the same time, we

cannot underestimate the convenience of an already

established image type. In the legend of Francis of

Assisi, the moment when he is accepted by the bishop

of Assisi is a turning point. While Francis is usually

represented standing in this scene, the painter of the

depicted him kneeling in

front of the bishop [Fig. 7). This modification rep-

resents a new pictorial solution in the iconographie

tradition of the saint, but the codex is full of depiction

of similar gestures: figures kneeling before a cleric,

even a preláte, are a favorite compositional typeA

There is no question that a visual language built

from a relatively small set of tools has its own limits.

The sélection of a given image type does not always

allow for expression of multiple layers of meaning.

When Giles gives a tunic to the ailing beggar, this act

also heals him. This is not expressed by the image,

however, smee the act is represented as a gesture of

alms giving [Fig. 8]a" In Pavia, Augustine not only

appears before the pilgrims, but also heals ail of

them. This aspect is completely lost in the pictureA

This is precisely why sometimes different image types

were used for similar situations: the makers of the

legendary wanted to emphasize different elements.

For example, motifs of temptation couid be repre-

sented by two figures lying next to each other or by

a gesture of embrace, which dérivés from the image

type of two people meeting. Sometimes temptation

was also expressed by the type used for exorcisms,

or by the motif of dancing hgures^ — it ail depended

on what was to be conveyed.

The image types are to a certain degree hexible.

When Mary Magdaleně procures forgiveness for a

-Vat. Lat. 8541, fol. 79v; LEVÁRDY 1973 (see m note 14),

Ag. 132.

3° Vat. Lat. 8541, fol. 94r; LEVÁRDY 1973 (see m note 14), Ag.

155.

3i Hermitage, 16931; LEVÁRDY 1973 (see m note 14), Ag.

120.

33 In the legends of Bernard (Vat. Lat. 8541, fol. 88v; LEVÁR-

DY 1973 (see in note 14), Ag. 142), St. Paul the Hermit (ibi-

dem, fol. 98r; ibidem, Ag. 161), Andrew (ibidem, fol. 20v; ibi-

dem, Ag. 40) and Benedict (ibidem, fol. 86r; ibidem, Ag. 139).

190