Perception is the meeting of the eye and the object.

However, from an aesthetic point of view this is an

encounter that can iead to admiration.

Light seduces the eye and the eye attracts colour.

Nobody will réfuté this direct relationship between

the eye and light; it is harder to concerne of one and

the other as one and the same thing. However, this

conception is easier if we say that there is a patent

light within the eye, which is excited by the tiniest

interior or exterior stimulus. Under the spell of our

imagination we can produce the clearest images even

in the darkness. In our dreams we see objects in broad

daylight; further, when the sight organ undergoes

mechanical stimulation, we see light and coloursA

Thus arises the act of looking: a gaze encom-

passed within a magic, immaterial contact; a sensa-

tion that hlters from inside us, producing a given

effect. Colour sight offers 'Wz o/ yW/%v /L#

/Wčwřt h 1 lence,

looking becomes the condition of the visibility of

colour and shows us that plastic rhetoric, rather than

being a more or less plausible theory, is a fact: the

fact that we are aware of a luminous attraction, a

lucid persuasion.

II. Rhetoric of Colour in Turner

After a general introduction into the meanmg of

"rhetoric of colour"', we try to analyse the "rheto-

ric of colour" in Turner's Lyyfp CoAwr

TAvry) — TW AHrAyy y/Ar /A DíAgř — ATor^r ÎF'hA'yg /A

TLčA gf [Fig. 1]. Together with its companion

piece - TA yf Af D<?Ag<?

[Fig. 3], dated 1842 — 1843, they were hrst exhibited

in 1843 but failed to attract much interest. The crit-

ics felt that Turner wanted to reinforce his image as

an eccentric person. In these paintings, he gives us

two brain twisters, and nobody beside himself could

solve those riddlesA

But indeed Turner with these paintings stands in

the long tradition of classical iconographie repre-

21 GOETHE 1992 (see m note 20), p. 64.

22 PLATO: AHM, 76c.

2^ 13.5.1843, quoted after FINBERG, A. J.: TA ly/ô A

A Ai. HL R H. Oxford 1961, p. 396; see also BUTLIN,

M. — JOLL, E.: TA PA/Axgr Ad- 4Í. HL TTrzzor. 2 vols. New

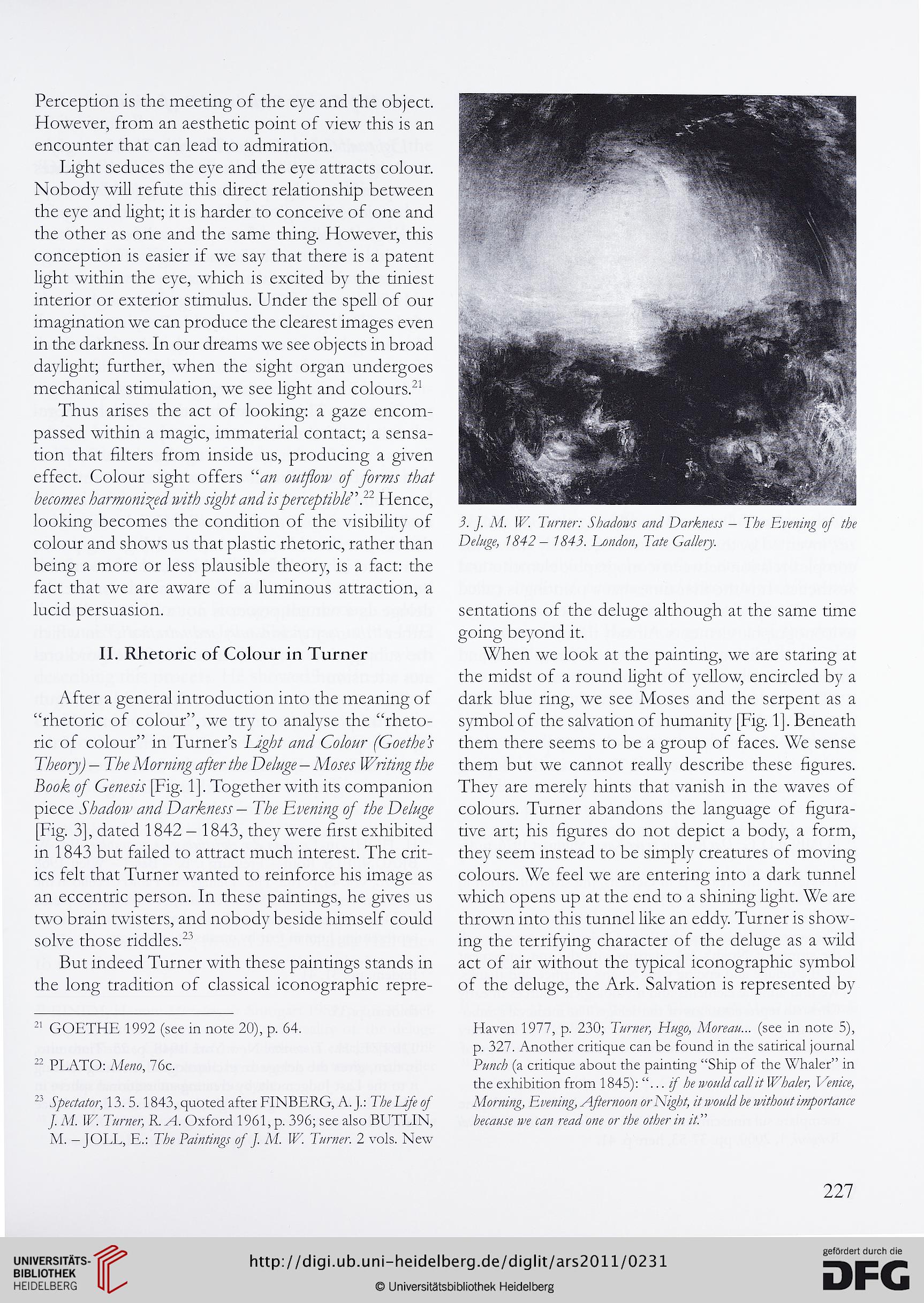

L. y. Ai. HL TAzzor.' AAAow — TA LroA/zg of Ař

Dř/zzgq / f 42 — / <$43. To/Ao^, Tkto GTAry.

sentations of the deluge although at the same time

going beyond it.

When we look at the painting, we are staring at

the midst of a round light of yellow, encircled by a

dark blue ring, we see Moses and the serpent as a

symbol of the salvation of humanity [Fig. 1]. Beneath

them there seems to be a group of faces. We sense

them but we cannot really describe these figures.

They are merely hints that vanish in the waves of

colours. Turner abandons the language of figura-

tive art; his figures do not depict a body, a form,

they seem instead to be simply créatures of moving

colours. We feel we are entermg into a dark tunnel

which opens up at the end to a shinmg light. We are

thrown into this tunnel like an eddy. Turner is show-

ing the terrifying character of the deluge as a wild

act of air without the typical iconographie symbol

of the deluge, the Ark. Salvation is represented by

Haven 1977, p. 230; TA%<?r; fT^w, AforMzz... (see in note 5),

p. 327. Another critique can be found in the satirical journal

PzwA (a critique about the painting "Ship of the Whaler" in

the exhibition from 1845): "... F ^ t<%f P HLGAr; 1 7w<rq

AiorA/zg, TTř%Ag, orNgA Pzroz/A A AtA^A/^orňžTZíť

zro c<%/? raA ozzo or /A otAr A A"

227

However, from an aesthetic point of view this is an

encounter that can iead to admiration.

Light seduces the eye and the eye attracts colour.

Nobody will réfuté this direct relationship between

the eye and light; it is harder to concerne of one and

the other as one and the same thing. However, this

conception is easier if we say that there is a patent

light within the eye, which is excited by the tiniest

interior or exterior stimulus. Under the spell of our

imagination we can produce the clearest images even

in the darkness. In our dreams we see objects in broad

daylight; further, when the sight organ undergoes

mechanical stimulation, we see light and coloursA

Thus arises the act of looking: a gaze encom-

passed within a magic, immaterial contact; a sensa-

tion that hlters from inside us, producing a given

effect. Colour sight offers 'Wz o/ yW/%v /L#

/Wčwřt h 1 lence,

looking becomes the condition of the visibility of

colour and shows us that plastic rhetoric, rather than

being a more or less plausible theory, is a fact: the

fact that we are aware of a luminous attraction, a

lucid persuasion.

II. Rhetoric of Colour in Turner

After a general introduction into the meanmg of

"rhetoric of colour"', we try to analyse the "rheto-

ric of colour" in Turner's Lyyfp CoAwr

TAvry) — TW AHrAyy y/Ar /A DíAgř — ATor^r ÎF'hA'yg /A

TLčA gf [Fig. 1]. Together with its companion

piece - TA yf Af D<?Ag<?

[Fig. 3], dated 1842 — 1843, they were hrst exhibited

in 1843 but failed to attract much interest. The crit-

ics felt that Turner wanted to reinforce his image as

an eccentric person. In these paintings, he gives us

two brain twisters, and nobody beside himself could

solve those riddlesA

But indeed Turner with these paintings stands in

the long tradition of classical iconographie repre-

21 GOETHE 1992 (see m note 20), p. 64.

22 PLATO: AHM, 76c.

2^ 13.5.1843, quoted after FINBERG, A. J.: TA ly/ô A

A Ai. HL R H. Oxford 1961, p. 396; see also BUTLIN,

M. — JOLL, E.: TA PA/Axgr Ad- 4Í. HL TTrzzor. 2 vols. New

L. y. Ai. HL TAzzor.' AAAow — TA LroA/zg of Ař

Dř/zzgq / f 42 — / <$43. To/Ao^, Tkto GTAry.

sentations of the deluge although at the same time

going beyond it.

When we look at the painting, we are staring at

the midst of a round light of yellow, encircled by a

dark blue ring, we see Moses and the serpent as a

symbol of the salvation of humanity [Fig. 1]. Beneath

them there seems to be a group of faces. We sense

them but we cannot really describe these figures.

They are merely hints that vanish in the waves of

colours. Turner abandons the language of figura-

tive art; his figures do not depict a body, a form,

they seem instead to be simply créatures of moving

colours. We feel we are entermg into a dark tunnel

which opens up at the end to a shinmg light. We are

thrown into this tunnel like an eddy. Turner is show-

ing the terrifying character of the deluge as a wild

act of air without the typical iconographie symbol

of the deluge, the Ark. Salvation is represented by

Haven 1977, p. 230; TA%<?r; fT^w, AforMzz... (see in note 5),

p. 327. Another critique can be found in the satirical journal

PzwA (a critique about the painting "Ship of the Whaler" in

the exhibition from 1845): "... F ^ t<%f P HLGAr; 1 7w<rq

AiorA/zg, TTř%Ag, orNgA Pzroz/A A AtA^A/^orňžTZíť

zro c<%/? raA ozzo or /A otAr A A"

227