created their own personal style and interprétations

of the topice"

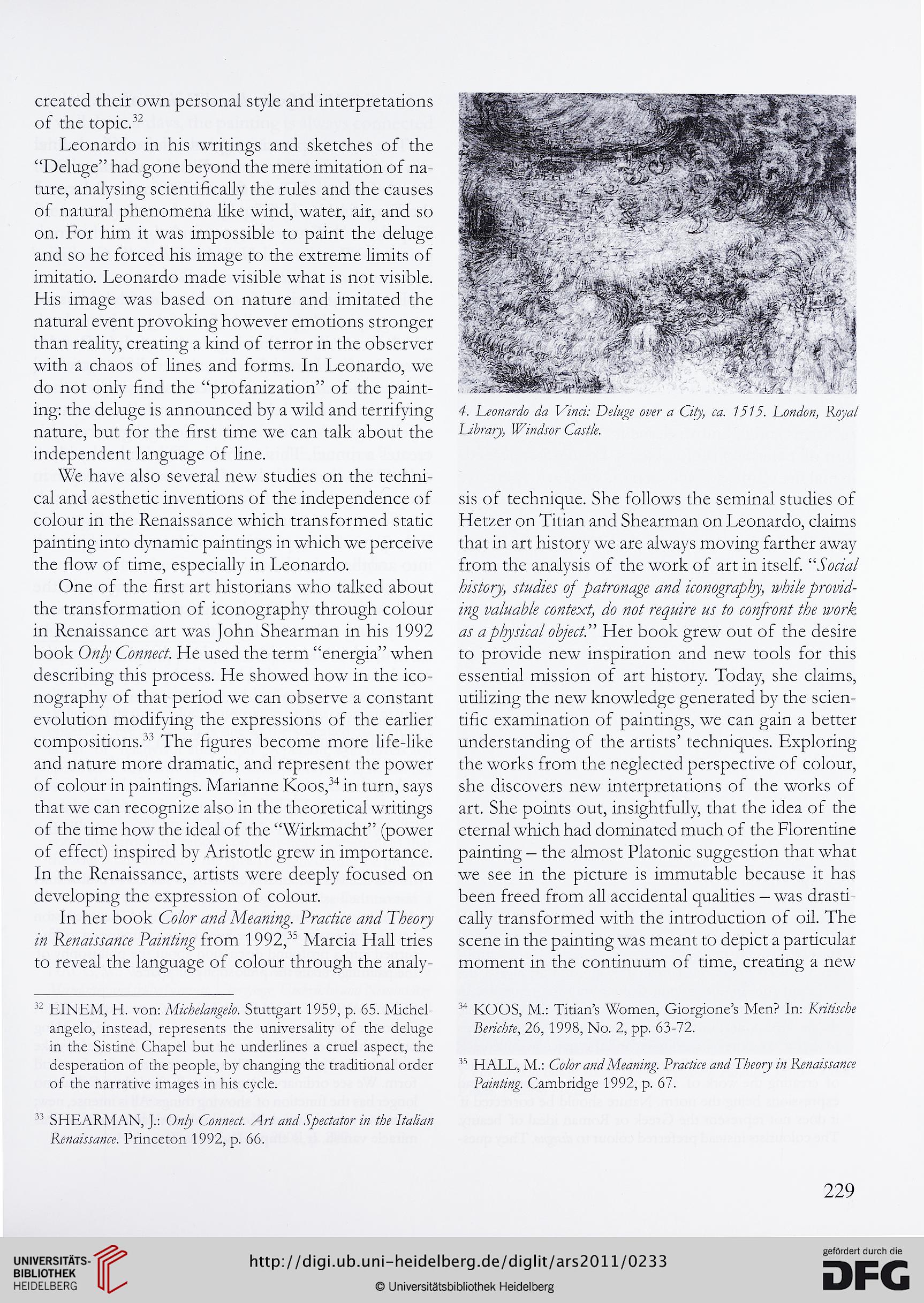

Leonardo in his writings and sketches of the

"Deluge" had gone beyond the mere imitation of na-

ture, analysing scientihcaiiy the rules and the causes

of natural phenomena like wind, water, air, and so

on. For him it was impossible to paint the deluge

and so he forced his image to the extreme limits of

imitatio. Leonardo made visible what is not visible.

His image was based on nature and imitated the

natural event provoking however émotions stronger

than reality, creating a kind of terror in the observer

with a chaos of lineš and forms. In Leonardo, we

do not only Und the "profanization" of the paint-

ing: the deluge is announced by a wild and terrifying

nature, but for the hrst time we can talk about the

independent language of line.

We have also several new studies on the techni-

cal and aesthetic inventions of the independence of

colour in the Renaissance which transformed static

painting into dynamic paintings in which we perceive

the how of time, especially in Leonardo.

One of the hrst art historians who talked about

the transformation of iconography through colour

in Renaissance art was John Shearman in his 1992

book 0%/y He ušed the term "energia" when

describing this process. He showed how in the ico-

nography of that period we can observe a constant

évolution modifying the expressions of the earlier

compositions/' The hgures become more life-like

and nature more dramatic, and represent the power

of colour in paintings. Marianne Koos,^ in turn, says

that we can recognize also in the theoretical writings

of the time how the ideal of the "Wirkmacht" (power

of effect) inspired by Aristode grew in importance.

In the Renaissance, artists were deeply focused on

developing the expression of colour.

In her book do/or PAort

A Rř/Mpr^rí' P^APyg from 1992,'" Marcia Hall tries

to reveal the language of colour through the analy-

EINEM, H. von: ALATzygPo. Stuttgart 1959, p. 65. Michel-

angelo, instead, represents the universality of the deluge

m the Sistine Chapel but he underlines a cruel aspect, the

desperation of the people, by changing the traditional order

of the narrative images in his cycle.

SHEARMAN, J.: 0%/y Hrř A tA

ILTMAMWř. Princeton 1992, p. 66.

L HywďfA A I7Æ ^ /L/i. Lo^P^, Roy^/

sis of technique. She follows the séminal studies of

Hetzer on Titian and Shearman on Leonardo, daims

that in art history we are always moving farther away

from the analysis of the work of art in itself. "dWA/

AAory o/ Po/jçgTypAy proRd-

777g A 77t h? C07p^0777' Ař 7^<97p

pPtdcA Her book grew out of the desire

to provide new inspiration and new tools for this

essential mission of art history. Today, she daims,

utilizing the new knowledge generated by the scien-

tihc examination of paintings, we can gain a better

understanding of the artists' techniques. Exploring

the works from the neglected perspective of colour,

she discovers new interprétations of the works of

art. She points out, insightfully, that the idea of the

eternal which had dominated much of the Florentine

painting — the almost Platonic suggestion that what

we see in the picture is immutable because it has

been freed from ail accidentai quaüties — was drasti-

cally transformed with the introduction of oil. The

scene in the painting was meant to depict a particular

moment in the continuum of time, creating a new

^ KOOS, M.: Titian's Women, Giorgione's Men? In: REAvA

BřEfAg 26,1998, No. 2, pp. 63-72.

^ HALL, M.: Pmr/rř^/TAřcryARř^A^rř

P^Tz'yg. Cambridge 1992, p. 67.

229

of the topice"

Leonardo in his writings and sketches of the

"Deluge" had gone beyond the mere imitation of na-

ture, analysing scientihcaiiy the rules and the causes

of natural phenomena like wind, water, air, and so

on. For him it was impossible to paint the deluge

and so he forced his image to the extreme limits of

imitatio. Leonardo made visible what is not visible.

His image was based on nature and imitated the

natural event provoking however émotions stronger

than reality, creating a kind of terror in the observer

with a chaos of lineš and forms. In Leonardo, we

do not only Und the "profanization" of the paint-

ing: the deluge is announced by a wild and terrifying

nature, but for the hrst time we can talk about the

independent language of line.

We have also several new studies on the techni-

cal and aesthetic inventions of the independence of

colour in the Renaissance which transformed static

painting into dynamic paintings in which we perceive

the how of time, especially in Leonardo.

One of the hrst art historians who talked about

the transformation of iconography through colour

in Renaissance art was John Shearman in his 1992

book 0%/y He ušed the term "energia" when

describing this process. He showed how in the ico-

nography of that period we can observe a constant

évolution modifying the expressions of the earlier

compositions/' The hgures become more life-like

and nature more dramatic, and represent the power

of colour in paintings. Marianne Koos,^ in turn, says

that we can recognize also in the theoretical writings

of the time how the ideal of the "Wirkmacht" (power

of effect) inspired by Aristode grew in importance.

In the Renaissance, artists were deeply focused on

developing the expression of colour.

In her book do/or PAort

A Rř/Mpr^rí' P^APyg from 1992,'" Marcia Hall tries

to reveal the language of colour through the analy-

EINEM, H. von: ALATzygPo. Stuttgart 1959, p. 65. Michel-

angelo, instead, represents the universality of the deluge

m the Sistine Chapel but he underlines a cruel aspect, the

desperation of the people, by changing the traditional order

of the narrative images in his cycle.

SHEARMAN, J.: 0%/y Hrř A tA

ILTMAMWř. Princeton 1992, p. 66.

L HywďfA A I7Æ ^ /L/i. Lo^P^, Roy^/

sis of technique. She follows the séminal studies of

Hetzer on Titian and Shearman on Leonardo, daims

that in art history we are always moving farther away

from the analysis of the work of art in itself. "dWA/

AAory o/ Po/jçgTypAy proRd-

777g A 77t h? C07p^0777' Ař 7^<97p

pPtdcA Her book grew out of the desire

to provide new inspiration and new tools for this

essential mission of art history. Today, she daims,

utilizing the new knowledge generated by the scien-

tihc examination of paintings, we can gain a better

understanding of the artists' techniques. Exploring

the works from the neglected perspective of colour,

she discovers new interprétations of the works of

art. She points out, insightfully, that the idea of the

eternal which had dominated much of the Florentine

painting — the almost Platonic suggestion that what

we see in the picture is immutable because it has

been freed from ail accidentai quaüties — was drasti-

cally transformed with the introduction of oil. The

scene in the painting was meant to depict a particular

moment in the continuum of time, creating a new

^ KOOS, M.: Titian's Women, Giorgione's Men? In: REAvA

BřEfAg 26,1998, No. 2, pp. 63-72.

^ HALL, M.: Pmr/rř^/TAřcryARř^A^rř

P^Tz'yg. Cambridge 1992, p. 67.

229