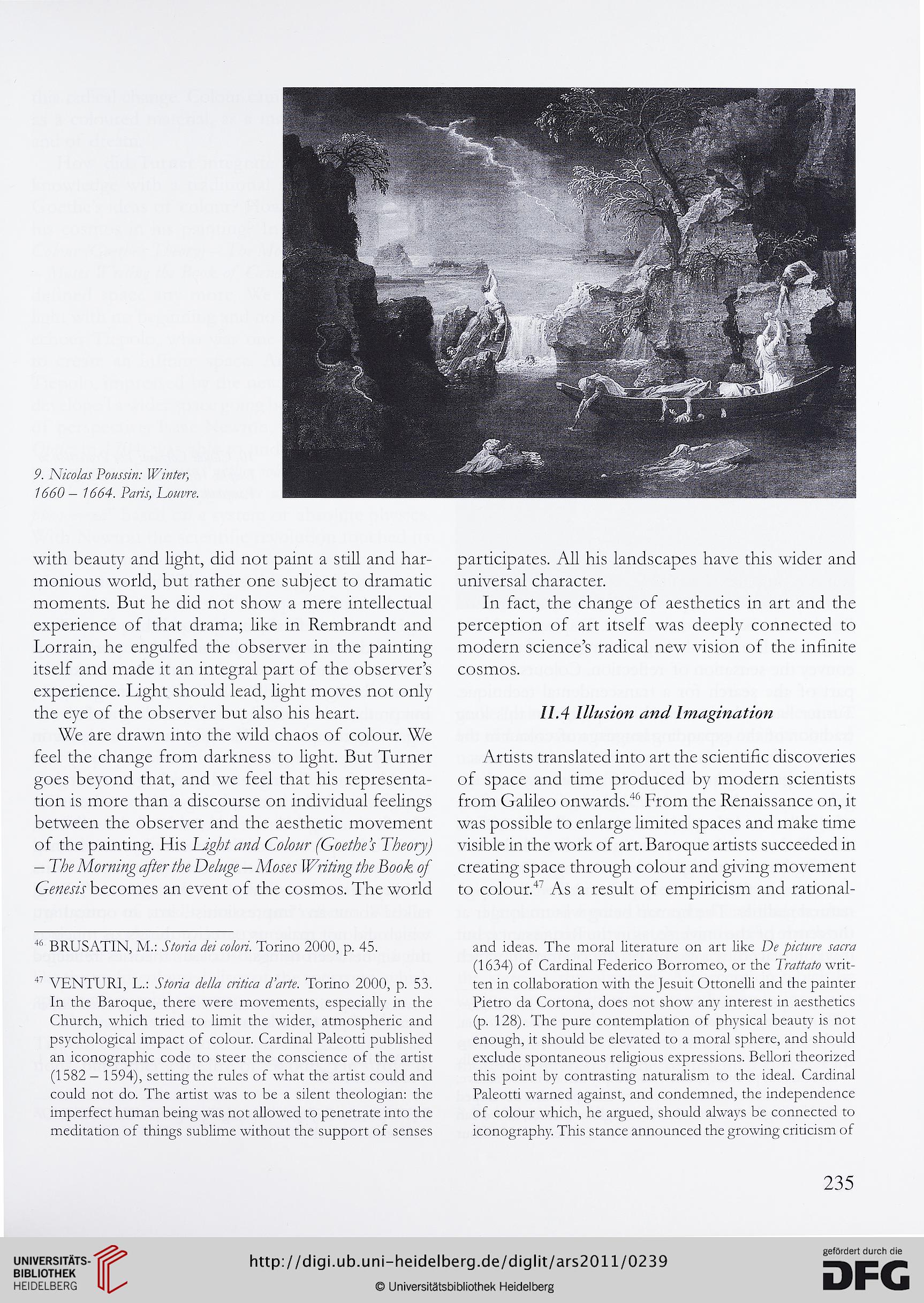

P. ALv/kt IPY^Zřt;

7440 — 7444. Pa*v'r, Lc^/ym

with beauty and light, did not paint a still and har-

monious world, but rather one subject to dramatic

moments. But he did not show a mere intellectual

expérience of that drama; like in Rembrandt and

Lorrain, he engulfed the observer in the painting

itself and made it an integral part of the observera

expérience. Light should lead, light moves not only

the eye of the observer but also his heart.

We are drawn into the wild chaos of colour. We

feel the change from darkness to light. But Turner

goes beyond that, and we feel that his représenta-

tion is more than a discourse on individual feelings

between the observer and the aesthetic movement

of the painting. His LLhw (GtWAr TAory)

- LA ALnLyg /A D<Ag<? — Afo^r ILAAzy /A BooA o/

becomes an event of the cosmos. The world

^ BRUSATIN, M.: Tknk kk<roBn. Torino 2000, p. 45.

^ VENTUR1, L.: Jknk AZk kkkř. Torino 2000, p. 53.

In the Baroque, there were movements, especially in the

Church, which tried to limit the wider, atmospheric and

psychological impact of colour. Cardinal Paleotti published

an iconographie code to steer the conscience of the artist

(1582 — 1594), setting the rules of what the artist could and

could not do. The artist was to be a silent theologian: the

imperfect human being was not allowed to penetrate into the

méditation of things sublime without the support of senses

participâtes. All his landscapes hâve this wider and

universal character.

In fact, the change of aesthetics in art and the

perception of art itself was deeply connected to

modem science's radical new vision of the infinite

cosmos.

77.4 7//?/.yz'(973

Artists translated into art the scientihc discoveries

of space and time produced by modem scientists

from Galileo onwardsA From the Renaissance on, it

was possible to enlarge limited spaces and make time

visible in the work of art. Baroque artists succeeded in

creating space through colour and giving movement

to colourT As a resuit of empiricism and rational-

and ideas. The moral literatuře on art like D<? jwm?

(1634) of Cardinal Federico Borromeo, or the Prkkk writ-

ten in collaboration with the Jesuit Ottonelli and the painter

Pietro da Cortona, does not show any interest in aesthetics

(p. 128). The pure contemplation of physical beauty is not

enough, it should be elevated to a moral sphere, and should

exclude spontaneous religious expressions. Bcllori theorized

this point by contrasting naturalism to the ideal. Cardinal

Paleotti warned against, and condemned, the independence

of colour which, he argued, should always be connected to

iconography. This stance announced the growing cnticism of

235

7440 — 7444. Pa*v'r, Lc^/ym

with beauty and light, did not paint a still and har-

monious world, but rather one subject to dramatic

moments. But he did not show a mere intellectual

expérience of that drama; like in Rembrandt and

Lorrain, he engulfed the observer in the painting

itself and made it an integral part of the observera

expérience. Light should lead, light moves not only

the eye of the observer but also his heart.

We are drawn into the wild chaos of colour. We

feel the change from darkness to light. But Turner

goes beyond that, and we feel that his représenta-

tion is more than a discourse on individual feelings

between the observer and the aesthetic movement

of the painting. His LLhw (GtWAr TAory)

- LA ALnLyg /A D<Ag<? — Afo^r ILAAzy /A BooA o/

becomes an event of the cosmos. The world

^ BRUSATIN, M.: Tknk kk<roBn. Torino 2000, p. 45.

^ VENTUR1, L.: Jknk AZk kkkř. Torino 2000, p. 53.

In the Baroque, there were movements, especially in the

Church, which tried to limit the wider, atmospheric and

psychological impact of colour. Cardinal Paleotti published

an iconographie code to steer the conscience of the artist

(1582 — 1594), setting the rules of what the artist could and

could not do. The artist was to be a silent theologian: the

imperfect human being was not allowed to penetrate into the

méditation of things sublime without the support of senses

participâtes. All his landscapes hâve this wider and

universal character.

In fact, the change of aesthetics in art and the

perception of art itself was deeply connected to

modem science's radical new vision of the infinite

cosmos.

77.4 7//?/.yz'(973

Artists translated into art the scientihc discoveries

of space and time produced by modem scientists

from Galileo onwardsA From the Renaissance on, it

was possible to enlarge limited spaces and make time

visible in the work of art. Baroque artists succeeded in

creating space through colour and giving movement

to colourT As a resuit of empiricism and rational-

and ideas. The moral literatuře on art like D<? jwm?

(1634) of Cardinal Federico Borromeo, or the Prkkk writ-

ten in collaboration with the Jesuit Ottonelli and the painter

Pietro da Cortona, does not show any interest in aesthetics

(p. 128). The pure contemplation of physical beauty is not

enough, it should be elevated to a moral sphere, and should

exclude spontaneous religious expressions. Bcllori theorized

this point by contrasting naturalism to the ideal. Cardinal

Paleotti warned against, and condemned, the independence

of colour which, he argued, should always be connected to

iconography. This stance announced the growing cnticism of

235