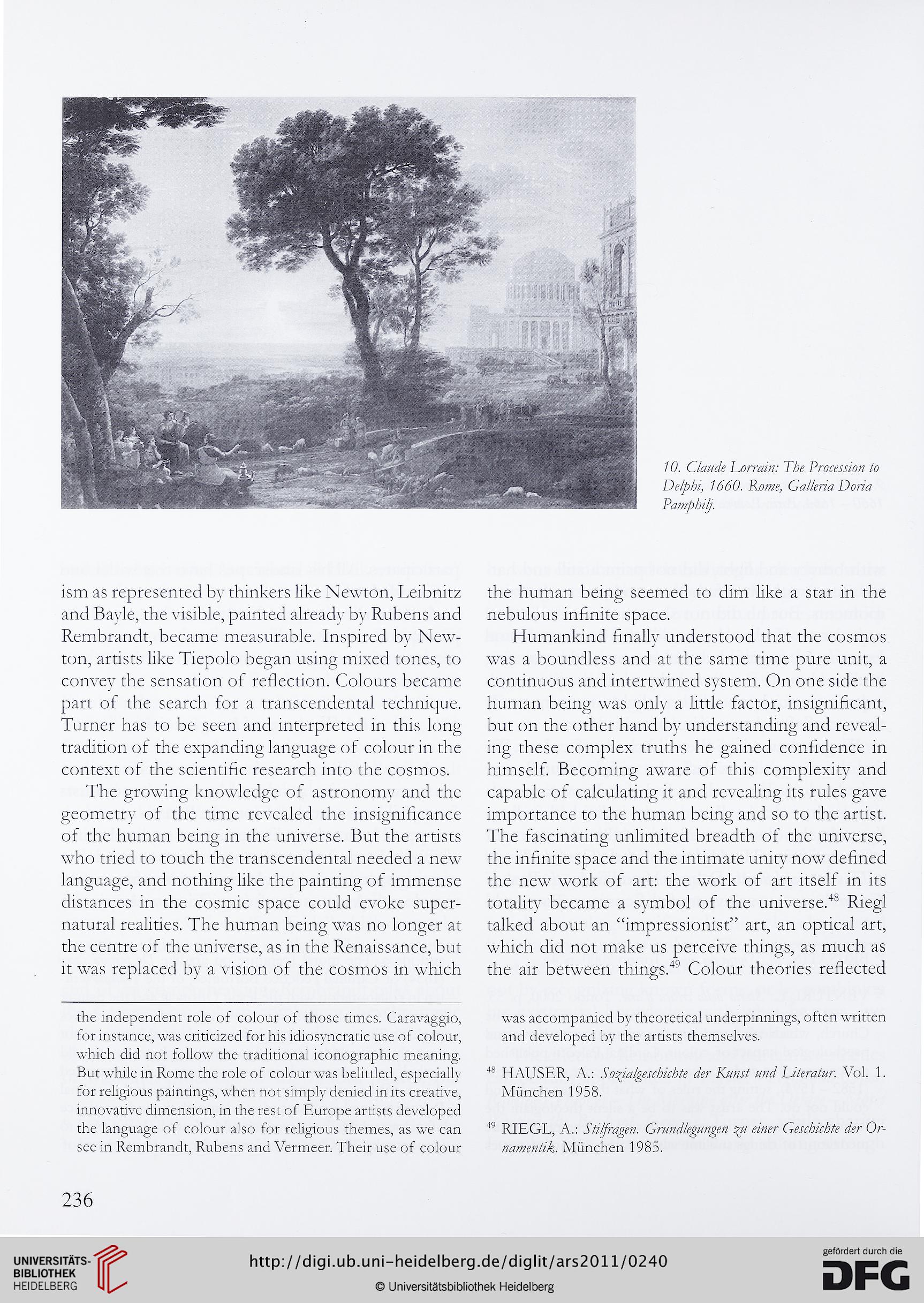

ism as represented bv thinkers like Newton, Leibnitz

and Bayle, the visible, painted already bv Rubens and

Rembrandt, became measurable. Inspired by New-

ton, artists like Tiepolo began using mixed toneš, to

convey the sensation of rehection. Colours became

part of the search for a transcendental technique.

Turner has to be seen and interpreted in this long

tradition of the expanding language of colour in the

context of the scientific research into the cosmos.

The growing knowledge of astronomy and the

geometry of the time revealed the insigniftcance

of the human being in the universe. But the artists

who tried to touch the transcendental needed a new

language, and nothing like the painting of immense

distances in the cosmic space could evoke super-

natural realities. The human being was no longer at

the centre of the universe, as in the Renaissance, but

ît was replaced by a vision of the cosmos in which

the independent role of colour of those times. Caravaggio,

for instance, was criticized for his idiosyncratic use of colour,

which did not follow the traditional iconographie meaning.

But while in Rome the role of colour was belittled, especially

for religious paintings, when not simply denied in its créative,

innovative dimension, in the rest of Europe artists developed

the language of colour also for religious thèmes, as we can

see in Rembrandt, Rubens and Vermeer. Their use of colour

the human being seemed to dim like a star in the

nebulous infinite space.

Humankind finally understood that the cosmos

was a boundless and at the same time pure unit, a

continuous and intertwined systém. On one side the

human being was only a little factor, insignifiant,

but on the other hand by understanding and reveal-

ing these complex truths he gained confidence in

himself. Becoming aware of this complexity and

capable of calculating it and revealing its rules gave

importance to the human being and so to the artist.

The fascinating unlimited breadth of the universe,

the infinite space and the intimate unity now dehned

the new work of art: the work of art itself in its

totality became a symbol of the universel Riegl

talked about an "impressionist" art, an optical art,

which did not make us perceive things, as much as

the air between thingsT Colour théories rehected

was accompanied by theoretical underpinnings, often written

and developed by the artists themselves.

^ HAUSER, A.: hoyM^vVdü.? ir Vol. 1.

München 1958.

^ RIEGL, A.: y# <?Ařf ir Or-

München 1985.

236