copied at least seven Correggio paintings41. One of

those was a Madonna eon il Bambino in braccio,

which may well have been the Madonna del latte. The

Madonna del latte was catalogued in Cardinal Piętro

Aldobrandini’s Roman inventories in 1603 and 1626.

In 1652 it was listed as a famosissima Madonna del

Corregio in Gottifredo Periberti’s collection in Romę

and by the end of the 17th century the painting

already belonged to Guzman, whom we know to be

connected with Maratti42. Artists seemed to take

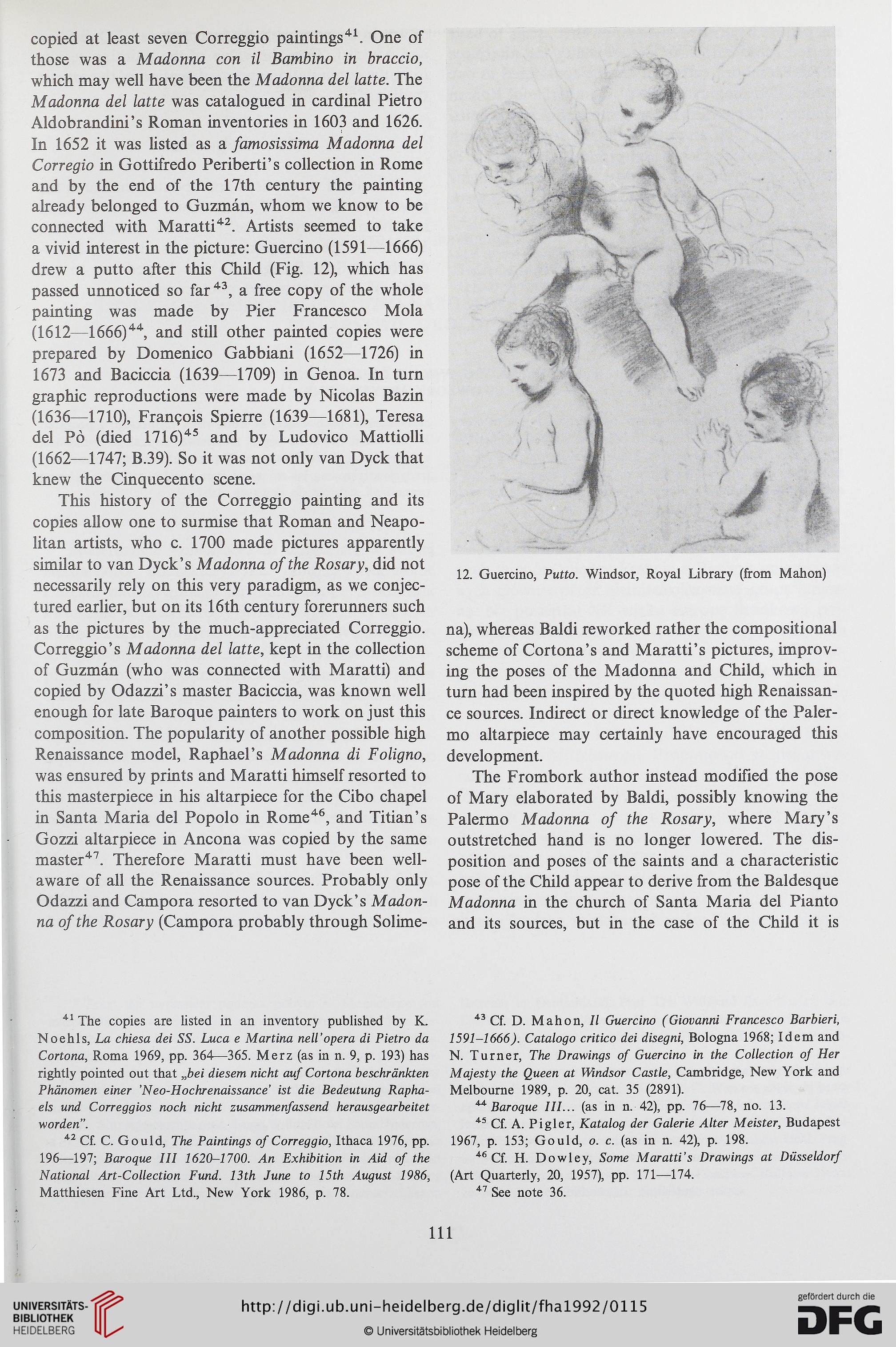

a vivid interest in the picture: Guercino (1591—1666)

drew a putto after this Child (Fig. 12), which has

passed unnoticed so far43, a free copy of the whole

painting was madę by Pier Francesco Mola

(1612—1666)44, and still other painted copies were

prepared by Domenico Gabbiani (1652—1726) in

1673 and Baciccia (1639—1709) in Genoa. In turn

graphic reproductions were madę by Nicolas Bazin

(1636—1710), Franęois Spierre (1639—1681), Teresa

del Pó (died 1716)45 and by Ludovico Mattiolli

(1662—1747; B.39). So it was not only van Dyck that

knew the Cinąuecento scene.

This history of the Correggio painting and its

copies allow one to surmise that Roman and Neapo-

litan artists, who c. 1700 madę pictures apparently

similar to van Dyck’s Madonna of the Rosary, did not

necessarily rely on this very paradigm, as we conjec-

tured earlier, but on its 16th century forerunners such

as the pictures by the much-appreciated Correggio.

Correggio’s Madonna del latte, kept in the collection

of Guzman (who was connected with Maratti) and

copied by Odazzi’s master Baciccia, was known well

enough for late Baroąue painters to work on just this

composition. The popularity of another possible high

Renaissance model, RaphaeFs Madonna di Foligno,

was ensured by prints and Maratti himself resorted to

this masterpiece in his altarpiece for the Cibo chapel

in Santa Maria del Popolo in Romę46, and Titian’s

Gozzi altarpiece in Ancona was copied by the same

master47. Therefore Maratti must have been well-

aware of all the Renaissance sources. Probably only

Odazzi and Campora resorted to van Dyck’s Madon-

na of the Rosary (Campora probably through Solime-

41 The copies are listed in an inventory published by K.

Noehls, La chiesa dei SS. Luca e Martina nelFopera di Piętro da

Cortona, Roma 1969, pp. 364—365. Mer z (as in n. 9, p. 193) has

rightly pointed out that „bei diesem nicht auf Cortona beschrankten

Phanomen einer ’Neo-Hochrenaissance ist die Bedeutung Rapha-

els und Correggios noch nicht zusammenfassend herausgearbeitet

worden”.

42 Cf. C. Gould, The Paintings of Correggio, Ithaca 1976, pp.

196—197; Baroąue III 1620-1700. An Exhibition in Aid of the

National Art-Collection Fund. 13th June to 15th August 1986,

Matthiesen Fine Art Ltd., New York 1986, p. 78.

12. Guercino, Putto. Windsor, Royal Library (from Mahoń)

na), whereas Baldi reworked rather the compositional

scheme of Cortona’s and Maratti’s pictures, improv-

ing the poses of the Madonna and Child, which in

turn had been inspired by the ąuoted high Renaissan-

ce sources. Indirect or direct knowledge of the Paler-

mo altarpiece may certainly have encouraged this

development.

The Frombork author instead modified the pose

of Mary elaborated by Baldi, possibly knowing the

Palermo Madonna of the Rosary, where Mary’s

outstretched hand is no longer lowered. The dis-

position and poses of the saints and a characteristic

pose of the Child appear to derive from the Baldesąue

Madonna in the church of Santa Maria del Pianto

and its sources, but in the case of the Child it is

43 Cf. D. Mahoń, II Guercino (Gioianni Francesco Barbieri,

1591-1666). Catalogo critico dei disegni, Bologna 1968; Idem and

N. Turner, The Drawings of Guercino in the Collection of Her

Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, Cambridge, New York and

Melbourne 1989, p. 20, cat. 35 (2891).

44 Baroąue III... (as in n. 42), pp. 76—78, no. 13.

45 Cf. A. Pi gier. Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister, Budapest

1967, p. 153; Gould, o. c. (as in n. 42), p. 198.

46 Cf. H. Dowley, Some Maratti’s Drawings at Dusseldorf

(Art Quarterly, 20, 1957), pp. 171—174.

47 See notę 36.

111

those was a Madonna eon il Bambino in braccio,

which may well have been the Madonna del latte. The

Madonna del latte was catalogued in Cardinal Piętro

Aldobrandini’s Roman inventories in 1603 and 1626.

In 1652 it was listed as a famosissima Madonna del

Corregio in Gottifredo Periberti’s collection in Romę

and by the end of the 17th century the painting

already belonged to Guzman, whom we know to be

connected with Maratti42. Artists seemed to take

a vivid interest in the picture: Guercino (1591—1666)

drew a putto after this Child (Fig. 12), which has

passed unnoticed so far43, a free copy of the whole

painting was madę by Pier Francesco Mola

(1612—1666)44, and still other painted copies were

prepared by Domenico Gabbiani (1652—1726) in

1673 and Baciccia (1639—1709) in Genoa. In turn

graphic reproductions were madę by Nicolas Bazin

(1636—1710), Franęois Spierre (1639—1681), Teresa

del Pó (died 1716)45 and by Ludovico Mattiolli

(1662—1747; B.39). So it was not only van Dyck that

knew the Cinąuecento scene.

This history of the Correggio painting and its

copies allow one to surmise that Roman and Neapo-

litan artists, who c. 1700 madę pictures apparently

similar to van Dyck’s Madonna of the Rosary, did not

necessarily rely on this very paradigm, as we conjec-

tured earlier, but on its 16th century forerunners such

as the pictures by the much-appreciated Correggio.

Correggio’s Madonna del latte, kept in the collection

of Guzman (who was connected with Maratti) and

copied by Odazzi’s master Baciccia, was known well

enough for late Baroąue painters to work on just this

composition. The popularity of another possible high

Renaissance model, RaphaeFs Madonna di Foligno,

was ensured by prints and Maratti himself resorted to

this masterpiece in his altarpiece for the Cibo chapel

in Santa Maria del Popolo in Romę46, and Titian’s

Gozzi altarpiece in Ancona was copied by the same

master47. Therefore Maratti must have been well-

aware of all the Renaissance sources. Probably only

Odazzi and Campora resorted to van Dyck’s Madon-

na of the Rosary (Campora probably through Solime-

41 The copies are listed in an inventory published by K.

Noehls, La chiesa dei SS. Luca e Martina nelFopera di Piętro da

Cortona, Roma 1969, pp. 364—365. Mer z (as in n. 9, p. 193) has

rightly pointed out that „bei diesem nicht auf Cortona beschrankten

Phanomen einer ’Neo-Hochrenaissance ist die Bedeutung Rapha-

els und Correggios noch nicht zusammenfassend herausgearbeitet

worden”.

42 Cf. C. Gould, The Paintings of Correggio, Ithaca 1976, pp.

196—197; Baroąue III 1620-1700. An Exhibition in Aid of the

National Art-Collection Fund. 13th June to 15th August 1986,

Matthiesen Fine Art Ltd., New York 1986, p. 78.

12. Guercino, Putto. Windsor, Royal Library (from Mahoń)

na), whereas Baldi reworked rather the compositional

scheme of Cortona’s and Maratti’s pictures, improv-

ing the poses of the Madonna and Child, which in

turn had been inspired by the ąuoted high Renaissan-

ce sources. Indirect or direct knowledge of the Paler-

mo altarpiece may certainly have encouraged this

development.

The Frombork author instead modified the pose

of Mary elaborated by Baldi, possibly knowing the

Palermo Madonna of the Rosary, where Mary’s

outstretched hand is no longer lowered. The dis-

position and poses of the saints and a characteristic

pose of the Child appear to derive from the Baldesąue

Madonna in the church of Santa Maria del Pianto

and its sources, but in the case of the Child it is

43 Cf. D. Mahoń, II Guercino (Gioianni Francesco Barbieri,

1591-1666). Catalogo critico dei disegni, Bologna 1968; Idem and

N. Turner, The Drawings of Guercino in the Collection of Her

Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, Cambridge, New York and

Melbourne 1989, p. 20, cat. 35 (2891).

44 Baroąue III... (as in n. 42), pp. 76—78, no. 13.

45 Cf. A. Pi gier. Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister, Budapest

1967, p. 153; Gould, o. c. (as in n. 42), p. 198.

46 Cf. H. Dowley, Some Maratti’s Drawings at Dusseldorf

(Art Quarterly, 20, 1957), pp. 171—174.

47 See notę 36.

111