Recent Domestic Architecture

originality; for the human mind has often among

its vagaries the curious habit of undervaluing

its own ideas and of over-estimating its collections

of facts. This is why the architects who copy the

old styles are always self-confident and dogmatic.

Anyone who differs from them is a “ charlatan ”;

they alone are the salt of the earth in matters of

architecture. A slight variation of an old motif,

a motif with which they have long been familiar

—this, to them, is a sure and a great sign of

originality; and so they spend their time at

ease in a mental atmosphere of paraphrases, and

are proud and happy.

A visit to the Architectural Room in this year’s

exhibition at the Academy will not fail to con-

firm the truth of the foregoing remarks. We

admit, indeed, that the drawings as a whole are

more workmanlike than usual, for their chief

defect is not a prettiness of handling which, to

the British workman, might possibly suggest a

water-colour by Birket Foster. In former exhibi-

tions many of the architects seemed anxious to

qualify their designs for the water-colour room;

this year they are much more practical, much less

picturesque; and the change is welcome. The

weakness to be deplored is one not of hand but of

mind ; there is a lack of independent judgment,

of fresh and vigorous thought, of freedom and

vitality of purpose. The drawings, indeed, are

nearer in touch with the Renaissance of long ago

than with that of our own time; and when every

allowance has been made for the causes of this

imitation, there is room left for regret and surprise.

As architecture inherits so much on its structural

side—so much that is permanently good—even the

laziest imitators might well be content, and, being

content, might well find pleasure in creating some-

thing all their own in the shape of ornament.

Also, it seems reasonable to believe that anything

obviously discordant with the needs of the present

day might be shunned quite as easily by architects

in their designs, as the use of obsolete words is

avoided by them in their speech. There is not

one among them who, in writing out a specifica-

tion, would hark back to the English of Sir John

Maundeville. Yet this would be neither .more

affected nor more ridiculous than building a

modern house with a mediaeval tower or keep.

Mr. Arnold Mitchell, in his design for Maesycru-

giau Manor, illustrated on p. 120, tries his hand at

a rather militant-looking tower without battlements,

and although he has made it as modestly serviceable

in the plan of his design as it well could be, it yet

seems out 01 place, for it does not at once suggest

a practical need that it could serve daily. Its

rooms, to be sure, would be useful and pleasing,

but not more so than the other rooms in the

house, which require for their protection no relic

of masonry reminiscent of early forms of warfare ;

and then, why should such a tower be turned from

its real significance and made into a symbol of

ease, of quiet, comfortable living ?

But if Mr. Arnold Mitchell is at fault in this

matter, he is quite right and at his best in the

other features of his design, the distribution of the

component parts of his Manor being particularly

fortunate.

The House at Wrotham, Kent, by Messrs.

Niven & Wigglesworth, illustrated upon page

115, is a distinct success, the design, modest

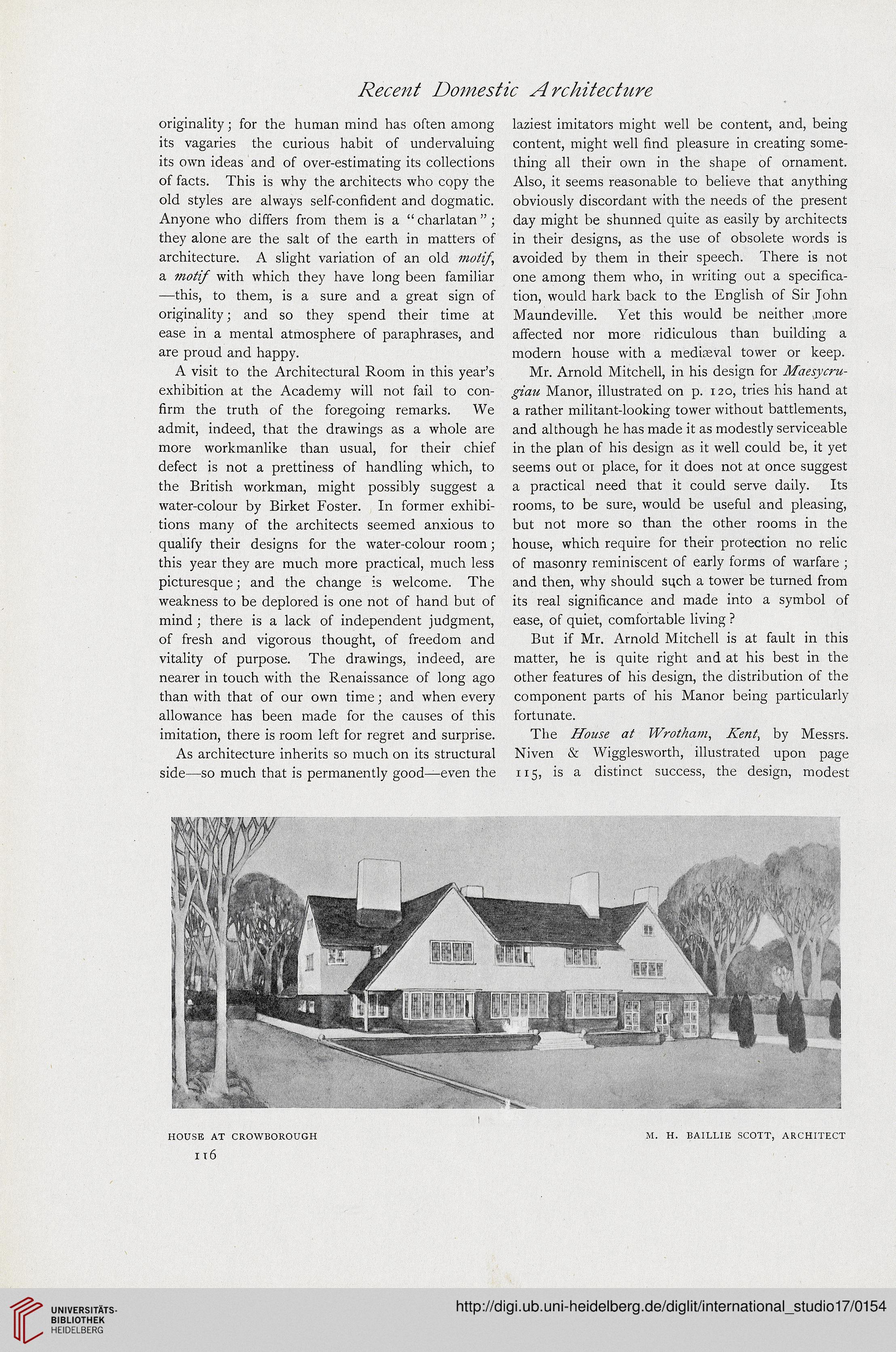

HOUSE AT CROWBOROUGH

I l6

M. H. BAILLIE SCOTT, ARCHITECT

originality; for the human mind has often among

its vagaries the curious habit of undervaluing

its own ideas and of over-estimating its collections

of facts. This is why the architects who copy the

old styles are always self-confident and dogmatic.

Anyone who differs from them is a “ charlatan ”;

they alone are the salt of the earth in matters of

architecture. A slight variation of an old motif,

a motif with which they have long been familiar

—this, to them, is a sure and a great sign of

originality; and so they spend their time at

ease in a mental atmosphere of paraphrases, and

are proud and happy.

A visit to the Architectural Room in this year’s

exhibition at the Academy will not fail to con-

firm the truth of the foregoing remarks. We

admit, indeed, that the drawings as a whole are

more workmanlike than usual, for their chief

defect is not a prettiness of handling which, to

the British workman, might possibly suggest a

water-colour by Birket Foster. In former exhibi-

tions many of the architects seemed anxious to

qualify their designs for the water-colour room;

this year they are much more practical, much less

picturesque; and the change is welcome. The

weakness to be deplored is one not of hand but of

mind ; there is a lack of independent judgment,

of fresh and vigorous thought, of freedom and

vitality of purpose. The drawings, indeed, are

nearer in touch with the Renaissance of long ago

than with that of our own time; and when every

allowance has been made for the causes of this

imitation, there is room left for regret and surprise.

As architecture inherits so much on its structural

side—so much that is permanently good—even the

laziest imitators might well be content, and, being

content, might well find pleasure in creating some-

thing all their own in the shape of ornament.

Also, it seems reasonable to believe that anything

obviously discordant with the needs of the present

day might be shunned quite as easily by architects

in their designs, as the use of obsolete words is

avoided by them in their speech. There is not

one among them who, in writing out a specifica-

tion, would hark back to the English of Sir John

Maundeville. Yet this would be neither .more

affected nor more ridiculous than building a

modern house with a mediaeval tower or keep.

Mr. Arnold Mitchell, in his design for Maesycru-

giau Manor, illustrated on p. 120, tries his hand at

a rather militant-looking tower without battlements,

and although he has made it as modestly serviceable

in the plan of his design as it well could be, it yet

seems out 01 place, for it does not at once suggest

a practical need that it could serve daily. Its

rooms, to be sure, would be useful and pleasing,

but not more so than the other rooms in the

house, which require for their protection no relic

of masonry reminiscent of early forms of warfare ;

and then, why should such a tower be turned from

its real significance and made into a symbol of

ease, of quiet, comfortable living ?

But if Mr. Arnold Mitchell is at fault in this

matter, he is quite right and at his best in the

other features of his design, the distribution of the

component parts of his Manor being particularly

fortunate.

The House at Wrotham, Kent, by Messrs.

Niven & Wigglesworth, illustrated upon page

115, is a distinct success, the design, modest

HOUSE AT CROWBOROUGH

I l6

M. H. BAILLIE SCOTT, ARCHITECT