328

Supra-regional contacts and the earliest metallurgy in southern Scandinavia during the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition

Random

High global efficiency

Low local efficiency

High global efficiency

High local efficiency

Lattice

Low global efficiency

High local efficiency

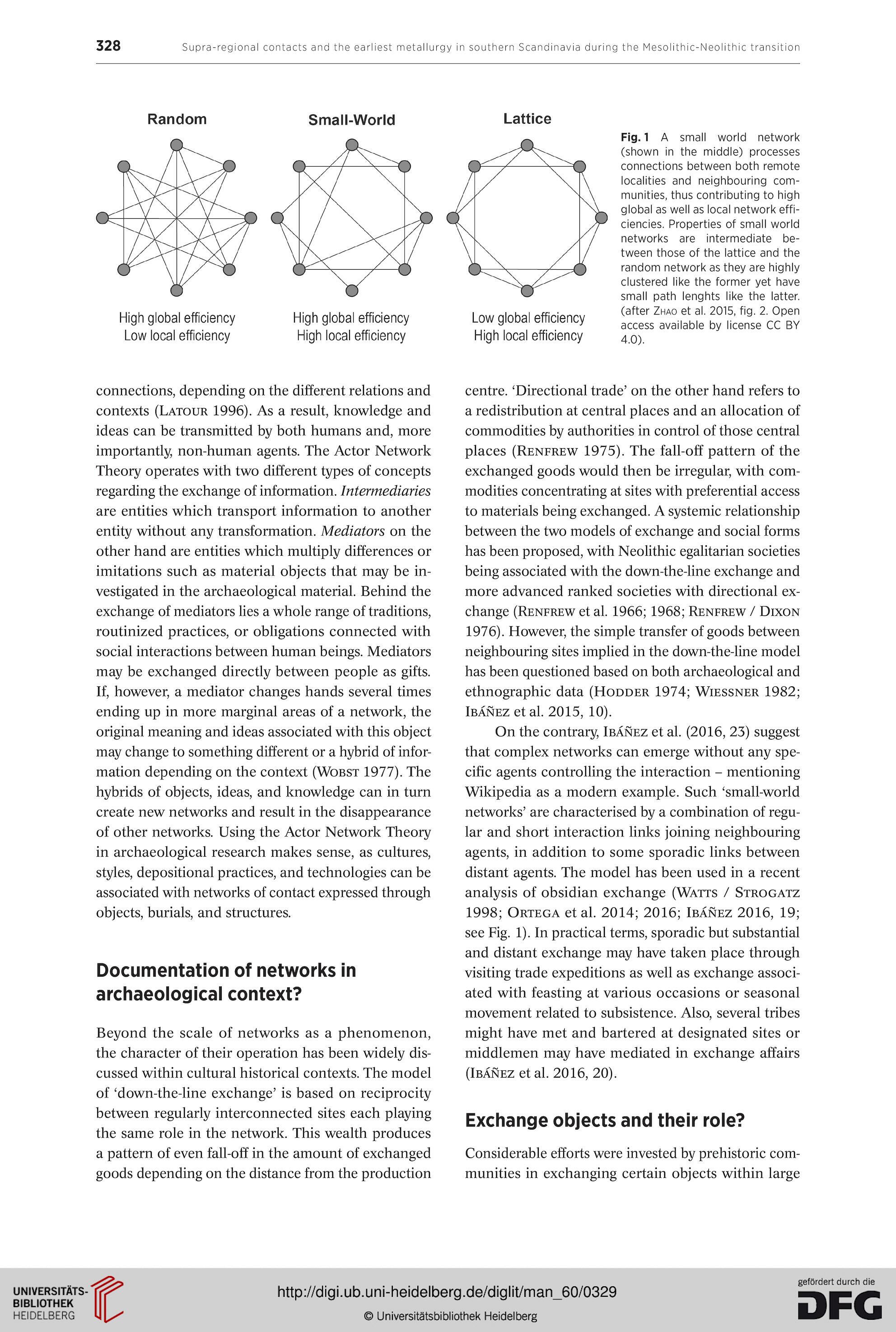

Fig. 1 A small world network

(shown in the middle) processes

connections between both remote

localities and neighbouring com-

munities, thus contributing to high

global as well as local network effi-

ciencies. Properties of small world

networks are intermediate be-

tween those of the lattice and the

random network as they are highly

clustered like the former yet have

small path lenghts like the latter,

(after Zhao et al. 2015, fig. 2. Open

access available by license CC BY

4.0).

connections, depending on the different relations and

contexts (Latour 1996). As a result, knowledge and

ideas can be transmitted by both humans and, more

importantly, non-human agents. The Actor Network

Theory operates with two different types of concepts

regarding the exchange of information. Intermediaries

are entities which transport information to another

entity without any transformation. Mediators on the

other hand are entities which multiply differences or

imitations such as material objects that may be in-

vestigated in the archaeological material. Behind the

exchange of mediators lies a whole range of traditions,

routinized practices, or obligations connected with

social interactions between human beings. Mediators

may be exchanged directly between people as gifts.

If, however, a mediator changes hands several times

ending up in more marginal areas of a network, the

original meaning and ideas associated with this object

may change to something different or a hybrid of infor-

mation depending on the context (Wobst 1977). The

hybrids of objects, ideas, and knowledge can in turn

create new networks and result in the disappearance

of other networks. Using the Actor Network Theory

in archaeological research makes sense, as cultures,

styles, depositional practices, and technologies can be

associated with networks of contact expressed through

objects, burials, and structures.

Documentation of networks in

archaeological context?

Beyond the scale of networks as a phenomenon,

the character of their operation has been widely dis-

cussed within cultural historical contexts. The model

of ‘down-the-line exchange’ is based on reciprocity

between regularly interconnected sites each playing

the same role in the network. This wealth produces

a pattern of even fall-off in the amount of exchanged

goods depending on the distance from the production

centre. ‘Directional trade’ on the other hand refers to

a redistribution at central places and an allocation of

commodities by authorities in control of those central

places (Renfrew 1975). The fall-off pattern of the

exchanged goods would then be irregular, with com-

modities concentrating at sites with preferential access

to materials being exchanged. A systemic relationship

between the two models of exchange and social forms

has been proposed, with Neolithic egalitarian societies

being associated with the down-the-line exchange and

more advanced ranked societies with directional ex-

change (Renfrew et al. 1966; 1968; Renfrew / Dixon

1976). However, the simple transfer of goods between

neighbouring sites implied in the down-the-line model

has been questioned based on both archaeological and

ethnographic data (Hodder 1974; Wiessner 1982;

Ibanez et al. 2015, 10).

On the contrary, Ibanez et al. (2016, 23) suggest

that complex networks can emerge without any spe-

cific agents controlling the interaction - mentioning

Wikipedia as a modern example. Such ‘small-world

networks’ are characterised by a combination of regu-

lar and short interaction links joining neighbouring

agents, in addition to some sporadic links between

distant agents. The model has been used in a recent

analysis of obsidian exchange (Watts / Strogatz

1998; Ortega et al. 2014; 2016; Ibanez 2016, 19;

see Fig. 1). In practical terms, sporadic but substantial

and distant exchange may have taken place through

visiting trade expeditions as well as exchange associ-

ated with feasting at various occasions or seasonal

movement related to subsistence. Also, several tribes

might have met and bartered at designated sites or

middlemen may have mediated in exchange affairs

(Ibanez et al. 2016, 20).

Exchange objects and their role?

Considerable efforts were invested by prehistoric com-

munities in exchanging certain objects within large

Supra-regional contacts and the earliest metallurgy in southern Scandinavia during the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition

Random

High global efficiency

Low local efficiency

High global efficiency

High local efficiency

Lattice

Low global efficiency

High local efficiency

Fig. 1 A small world network

(shown in the middle) processes

connections between both remote

localities and neighbouring com-

munities, thus contributing to high

global as well as local network effi-

ciencies. Properties of small world

networks are intermediate be-

tween those of the lattice and the

random network as they are highly

clustered like the former yet have

small path lenghts like the latter,

(after Zhao et al. 2015, fig. 2. Open

access available by license CC BY

4.0).

connections, depending on the different relations and

contexts (Latour 1996). As a result, knowledge and

ideas can be transmitted by both humans and, more

importantly, non-human agents. The Actor Network

Theory operates with two different types of concepts

regarding the exchange of information. Intermediaries

are entities which transport information to another

entity without any transformation. Mediators on the

other hand are entities which multiply differences or

imitations such as material objects that may be in-

vestigated in the archaeological material. Behind the

exchange of mediators lies a whole range of traditions,

routinized practices, or obligations connected with

social interactions between human beings. Mediators

may be exchanged directly between people as gifts.

If, however, a mediator changes hands several times

ending up in more marginal areas of a network, the

original meaning and ideas associated with this object

may change to something different or a hybrid of infor-

mation depending on the context (Wobst 1977). The

hybrids of objects, ideas, and knowledge can in turn

create new networks and result in the disappearance

of other networks. Using the Actor Network Theory

in archaeological research makes sense, as cultures,

styles, depositional practices, and technologies can be

associated with networks of contact expressed through

objects, burials, and structures.

Documentation of networks in

archaeological context?

Beyond the scale of networks as a phenomenon,

the character of their operation has been widely dis-

cussed within cultural historical contexts. The model

of ‘down-the-line exchange’ is based on reciprocity

between regularly interconnected sites each playing

the same role in the network. This wealth produces

a pattern of even fall-off in the amount of exchanged

goods depending on the distance from the production

centre. ‘Directional trade’ on the other hand refers to

a redistribution at central places and an allocation of

commodities by authorities in control of those central

places (Renfrew 1975). The fall-off pattern of the

exchanged goods would then be irregular, with com-

modities concentrating at sites with preferential access

to materials being exchanged. A systemic relationship

between the two models of exchange and social forms

has been proposed, with Neolithic egalitarian societies

being associated with the down-the-line exchange and

more advanced ranked societies with directional ex-

change (Renfrew et al. 1966; 1968; Renfrew / Dixon

1976). However, the simple transfer of goods between

neighbouring sites implied in the down-the-line model

has been questioned based on both archaeological and

ethnographic data (Hodder 1974; Wiessner 1982;

Ibanez et al. 2015, 10).

On the contrary, Ibanez et al. (2016, 23) suggest

that complex networks can emerge without any spe-

cific agents controlling the interaction - mentioning

Wikipedia as a modern example. Such ‘small-world

networks’ are characterised by a combination of regu-

lar and short interaction links joining neighbouring

agents, in addition to some sporadic links between

distant agents. The model has been used in a recent

analysis of obsidian exchange (Watts / Strogatz

1998; Ortega et al. 2014; 2016; Ibanez 2016, 19;

see Fig. 1). In practical terms, sporadic but substantial

and distant exchange may have taken place through

visiting trade expeditions as well as exchange associ-

ated with feasting at various occasions or seasonal

movement related to subsistence. Also, several tribes

might have met and bartered at designated sites or

middlemen may have mediated in exchange affairs

(Ibanez et al. 2016, 20).

Exchange objects and their role?

Considerable efforts were invested by prehistoric com-

munities in exchanging certain objects within large