The Future of Wood-Engraving

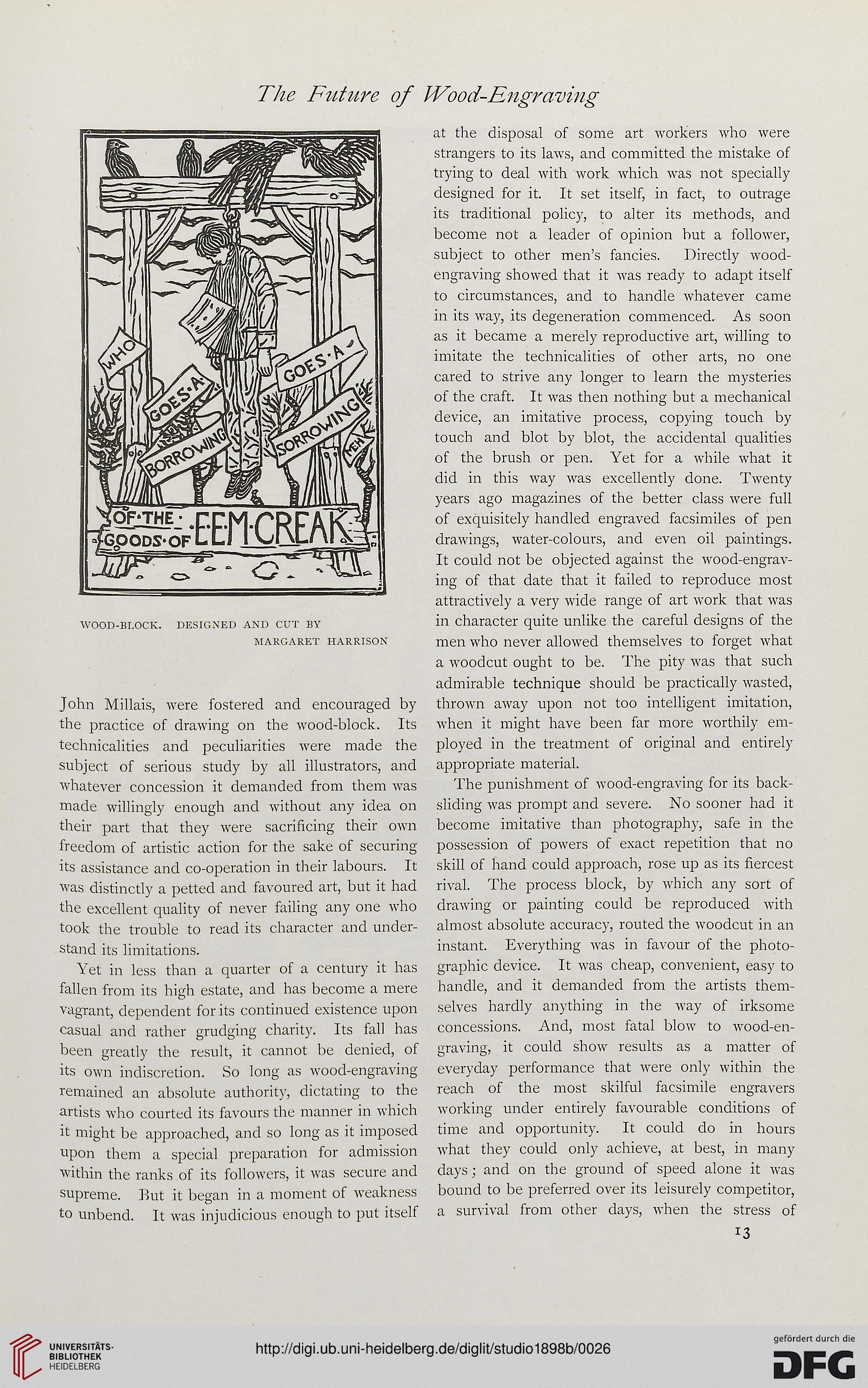

WOOD-BLOCK. DESIGNED AND CUT BY

MARGARET HARRISON

John Millais, were fostered and encouraged by

the practice of drawing on the wood-block. Its

technicalities and peculiarities were made the

subject of serious study by all illustrators, and

whatever concession it demanded from them was

made willingly enough and without any idea on

their part that they were sacrificing their own

freedom of artistic action for the sake of securing

its assistance and co-operation in their labours. It

was distinctly a petted and favoured art, but it had

the excellent quality of never failing any one who

took the trouble to read its character and under-

stand its limitations.

Yet in less than a quarter of a century it has

fallen from its high estate, and has become a mere

vagrant, dependent for its continued existence upon

casual and rather grudging charity. Its fall has

been greatly the result, it cannot be denied, of

its own indiscretion. So long as wood-engraving

remained an absolute authority, dictating to the

artists who courted its favours the manner in which

it might be approached, and so long as it imposed

upon them a special preparation for admission

within the ranks of its followers, it was secure and

supreme. But it began in a moment of weakness

to unbend. It was injudicious enough to put itself

at the disposal of some art workers who were

strangers to its laws, and committed the mistake of

trying to deal with work which was not specially

designed for it. It set itself, in fact, to outrage

its traditional policy, to alter its methods, and

become not a leader of opinion but a follower,

subject to other men’s fancies. Directly wood-

engraving showed that it was ready to adapt itself

to circumstances, and to handle whatever came

in its way, its degeneration commenced. As soon

as it became a merely reproductive art, willing to

imitate the technicalities of other arts, no one

cared to strive any longer to learn the mysteries

of the craft. It was then nothing but a mechanical

device, an imitative process, copying touch by

touch and blot by blot, the accidental qualities

of the brush or pen. Yet for a while what it

did in this way was excellently done. Twenty

years ago magazines of the better class were full

of exquisitely handled engraved facsimiles of pen

drawings, water-colours, and even oil paintings.

It could not be objected against the wood-engrav-

ing of that date that it failed to reproduce most

attractively a very wide range of art work that was

in character quite unlike the careful designs of the

men who never allowed themselves to forget what

a woodcut ought to be. The pity was that such

admirable technique should be practically wasted,

thrown away upon not too intelligent imitation,

when it might have been far more worthily em-

ployed in the treatment of original and entirely

appropriate material.

The punishment of wood-engraving for its back-

sliding was prompt and severe. No sooner had it

become imitative than photography, safe in the

possession of powers of exact repetition that no

skill of hand could approach, rose up as its fiercest

rival. The process block, by which any sort of

drawing or painting could be reproduced with

almost absolute accuracy, routed the woodcut in an

instant. Everything was in favour of the photo-

graphic device. It was cheap, convenient, easy to

handle, and it demanded from the artists them-

selves hardly anything in the way of irksome

concessions. And, most fatal blow to wood-en-

graving, it could show results as a matter of

everyday performance that were only within the

reach of the most skilful facsimile engravers

working under entirely favourable conditions of

time and opportunity. It could do in hours

what they could only achieve, at best, in many

days; and on the ground of speed alone it was

bound to be preferred over its leisurely competitor,

a survival from other days, when the stress of

*3

WOOD-BLOCK. DESIGNED AND CUT BY

MARGARET HARRISON

John Millais, were fostered and encouraged by

the practice of drawing on the wood-block. Its

technicalities and peculiarities were made the

subject of serious study by all illustrators, and

whatever concession it demanded from them was

made willingly enough and without any idea on

their part that they were sacrificing their own

freedom of artistic action for the sake of securing

its assistance and co-operation in their labours. It

was distinctly a petted and favoured art, but it had

the excellent quality of never failing any one who

took the trouble to read its character and under-

stand its limitations.

Yet in less than a quarter of a century it has

fallen from its high estate, and has become a mere

vagrant, dependent for its continued existence upon

casual and rather grudging charity. Its fall has

been greatly the result, it cannot be denied, of

its own indiscretion. So long as wood-engraving

remained an absolute authority, dictating to the

artists who courted its favours the manner in which

it might be approached, and so long as it imposed

upon them a special preparation for admission

within the ranks of its followers, it was secure and

supreme. But it began in a moment of weakness

to unbend. It was injudicious enough to put itself

at the disposal of some art workers who were

strangers to its laws, and committed the mistake of

trying to deal with work which was not specially

designed for it. It set itself, in fact, to outrage

its traditional policy, to alter its methods, and

become not a leader of opinion but a follower,

subject to other men’s fancies. Directly wood-

engraving showed that it was ready to adapt itself

to circumstances, and to handle whatever came

in its way, its degeneration commenced. As soon

as it became a merely reproductive art, willing to

imitate the technicalities of other arts, no one

cared to strive any longer to learn the mysteries

of the craft. It was then nothing but a mechanical

device, an imitative process, copying touch by

touch and blot by blot, the accidental qualities

of the brush or pen. Yet for a while what it

did in this way was excellently done. Twenty

years ago magazines of the better class were full

of exquisitely handled engraved facsimiles of pen

drawings, water-colours, and even oil paintings.

It could not be objected against the wood-engrav-

ing of that date that it failed to reproduce most

attractively a very wide range of art work that was

in character quite unlike the careful designs of the

men who never allowed themselves to forget what

a woodcut ought to be. The pity was that such

admirable technique should be practically wasted,

thrown away upon not too intelligent imitation,

when it might have been far more worthily em-

ployed in the treatment of original and entirely

appropriate material.

The punishment of wood-engraving for its back-

sliding was prompt and severe. No sooner had it

become imitative than photography, safe in the

possession of powers of exact repetition that no

skill of hand could approach, rose up as its fiercest

rival. The process block, by which any sort of

drawing or painting could be reproduced with

almost absolute accuracy, routed the woodcut in an

instant. Everything was in favour of the photo-

graphic device. It was cheap, convenient, easy to

handle, and it demanded from the artists them-

selves hardly anything in the way of irksome

concessions. And, most fatal blow to wood-en-

graving, it could show results as a matter of

everyday performance that were only within the

reach of the most skilful facsimile engravers

working under entirely favourable conditions of

time and opportunity. It could do in hours

what they could only achieve, at best, in many

days; and on the ground of speed alone it was

bound to be preferred over its leisurely competitor,

a survival from other days, when the stress of

*3