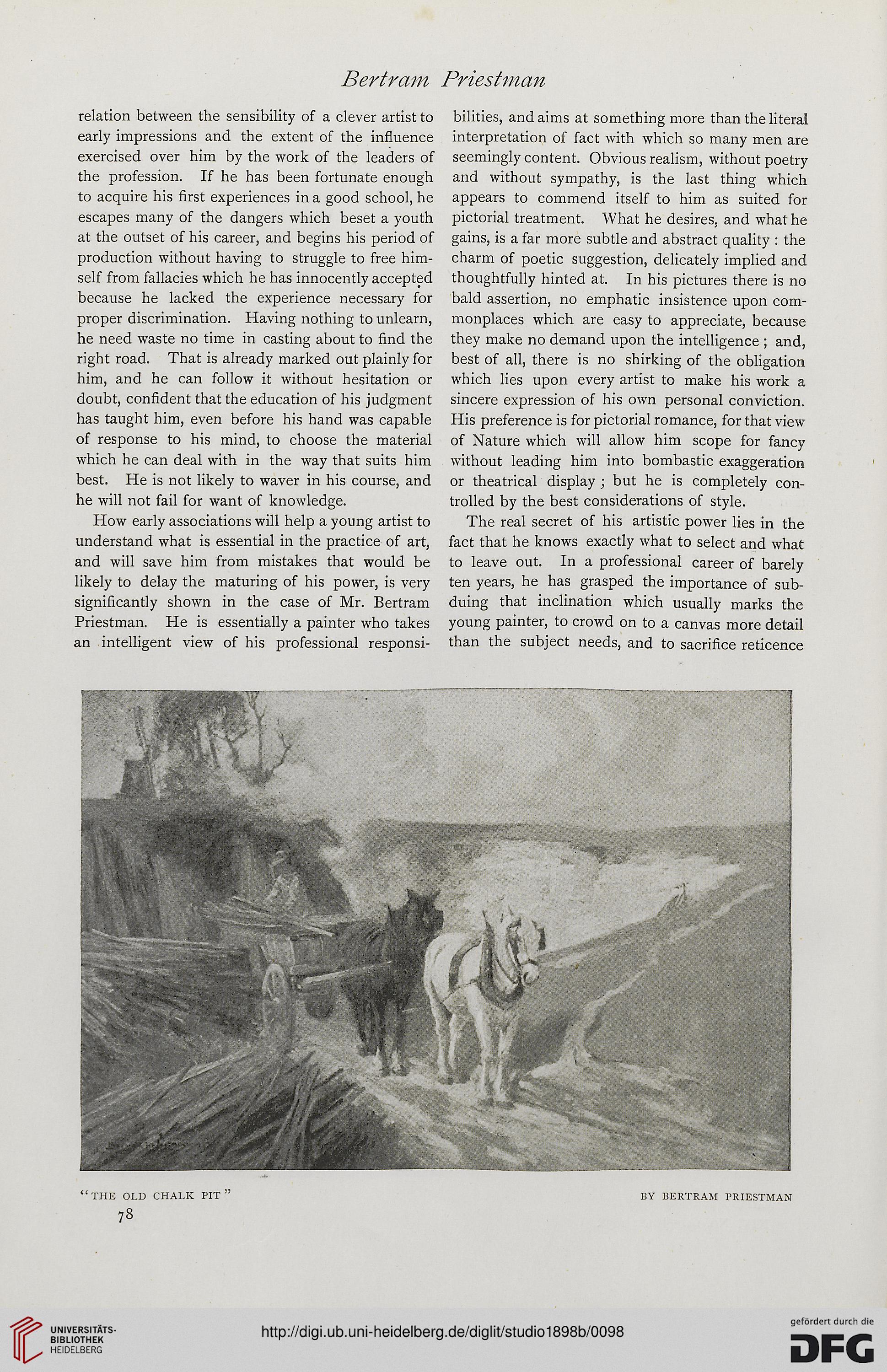

Bertram Priestman

relation between the sensibility of a clever artist to

early impressions and the extent of the influence

exercised over him by the work of the leaders of

the profession. If he has been fortunate enough

to acquire his first experiences in a good school, he

escapes many of the dangers which beset a youth

at the outset of his career, and begins his period of

production without having to struggle to free him-

self from fallacies which he has innocently accepted

because he lacked the experience necessary for

proper discrimination. Having nothing to unlearn,

he need waste no time in casting about to find the

right road. That is already marked out plainly for

him, and he can follow it without hesitation or

doubt, confident that the education of his judgment

has taught him, even before his hand was capable

of response to his mind, to choose the material

which he can deal with in the way that suits him

best. He is not likely to waver in his course, and

he will not fail for want of knowledge.

How early associations will help a young artist to

understand what is essential in the practice of art,

and will save him from mistakes that would be

likely to delay the maturing of his power, is very

significantly shown in the case of Mr. Bertram

Priestman. He is essentially a painter who takes

an intelligent view of his professional responsi-

bilities, and aims at something more than the literal

interpretation of fact with which so many men are

seemingly content. Obvious realism, without poetry

and without sympathy, is the last thing which

appears to commend itself to him as suited for

pictorial treatment. What he desires, and what he

gains, is a far more subtle and abstract quality : the

charm of poetic suggestion, delicately implied and

thoughtfully hinted at. In his pictures there is no

bald assertion, no emphatic insistence upon com-

monplaces which are easy to appreciate, because

they make no demand upon the intelligence ; and,

best of all, there is no shirking of the obligation

which lies upon every artist to make his work a

sincere expression of his own personal conviction.

His preference is for pictorial romance, for that view

of Nature which will allow him scope for fancy

without leading him into bombastic exaggeration

or theatrical display ; but he is completely con-

trolled by the best considerations of style.

The real secret of his artistic power lies in the

fact that he knows exactly what to select and what

to leave out. In a professional career of barely

ten years, he has grasped the importance of sub-

duing that inclination which usually marks the

young painter, to crowd on to a canvas more detail

than the subject needs, and to sacrifice reticence

relation between the sensibility of a clever artist to

early impressions and the extent of the influence

exercised over him by the work of the leaders of

the profession. If he has been fortunate enough

to acquire his first experiences in a good school, he

escapes many of the dangers which beset a youth

at the outset of his career, and begins his period of

production without having to struggle to free him-

self from fallacies which he has innocently accepted

because he lacked the experience necessary for

proper discrimination. Having nothing to unlearn,

he need waste no time in casting about to find the

right road. That is already marked out plainly for

him, and he can follow it without hesitation or

doubt, confident that the education of his judgment

has taught him, even before his hand was capable

of response to his mind, to choose the material

which he can deal with in the way that suits him

best. He is not likely to waver in his course, and

he will not fail for want of knowledge.

How early associations will help a young artist to

understand what is essential in the practice of art,

and will save him from mistakes that would be

likely to delay the maturing of his power, is very

significantly shown in the case of Mr. Bertram

Priestman. He is essentially a painter who takes

an intelligent view of his professional responsi-

bilities, and aims at something more than the literal

interpretation of fact with which so many men are

seemingly content. Obvious realism, without poetry

and without sympathy, is the last thing which

appears to commend itself to him as suited for

pictorial treatment. What he desires, and what he

gains, is a far more subtle and abstract quality : the

charm of poetic suggestion, delicately implied and

thoughtfully hinted at. In his pictures there is no

bald assertion, no emphatic insistence upon com-

monplaces which are easy to appreciate, because

they make no demand upon the intelligence ; and,

best of all, there is no shirking of the obligation

which lies upon every artist to make his work a

sincere expression of his own personal conviction.

His preference is for pictorial romance, for that view

of Nature which will allow him scope for fancy

without leading him into bombastic exaggeration

or theatrical display ; but he is completely con-

trolled by the best considerations of style.

The real secret of his artistic power lies in the

fact that he knows exactly what to select and what

to leave out. In a professional career of barely

ten years, he has grasped the importance of sub-

duing that inclination which usually marks the

young painter, to crowd on to a canvas more detail

than the subject needs, and to sacrifice reticence