Furniture for the New Palace, Darmstadt

The interior is painted in white, green, and orange

on a light green ground.

It might readily be supposed that in an age

which is characterised by so much attention to

education at least the average tradesman might be

supposed to understand his own trade, and that

good and intelligent workmanship, if not a drug in

the market, should not at least be far to seek.

That such is not the case all those who under-

stand and appreciate excellence of workmanship

will be willing to concede.

The old traditional knowledge is dying or dead,

and as yet we have nothing to replace it. The

prevalence of the commercial spirit, the influence

of machinery on the minds and hands of the

workman, and, above all, the want of perception

on the part of the public, are all causes

to retard the development of a true

knowledge of craftsmanship.

The superficial and mechanical finish

of the average suite of furniture is all

that is now demanded, and, to borrow

an analogy from another domain of art,

it is as if one were to cheerfully substi-

tute the arid and mechanical precision

of the musical box for the personal and

vital charm of the violin.

The designer and the workman who

realises his design should bear some-

what the same relation to each other as

the composer and the performer. The

•one interprets the ideas of the other,

.and in doing so adds his own personal

note to the final result.

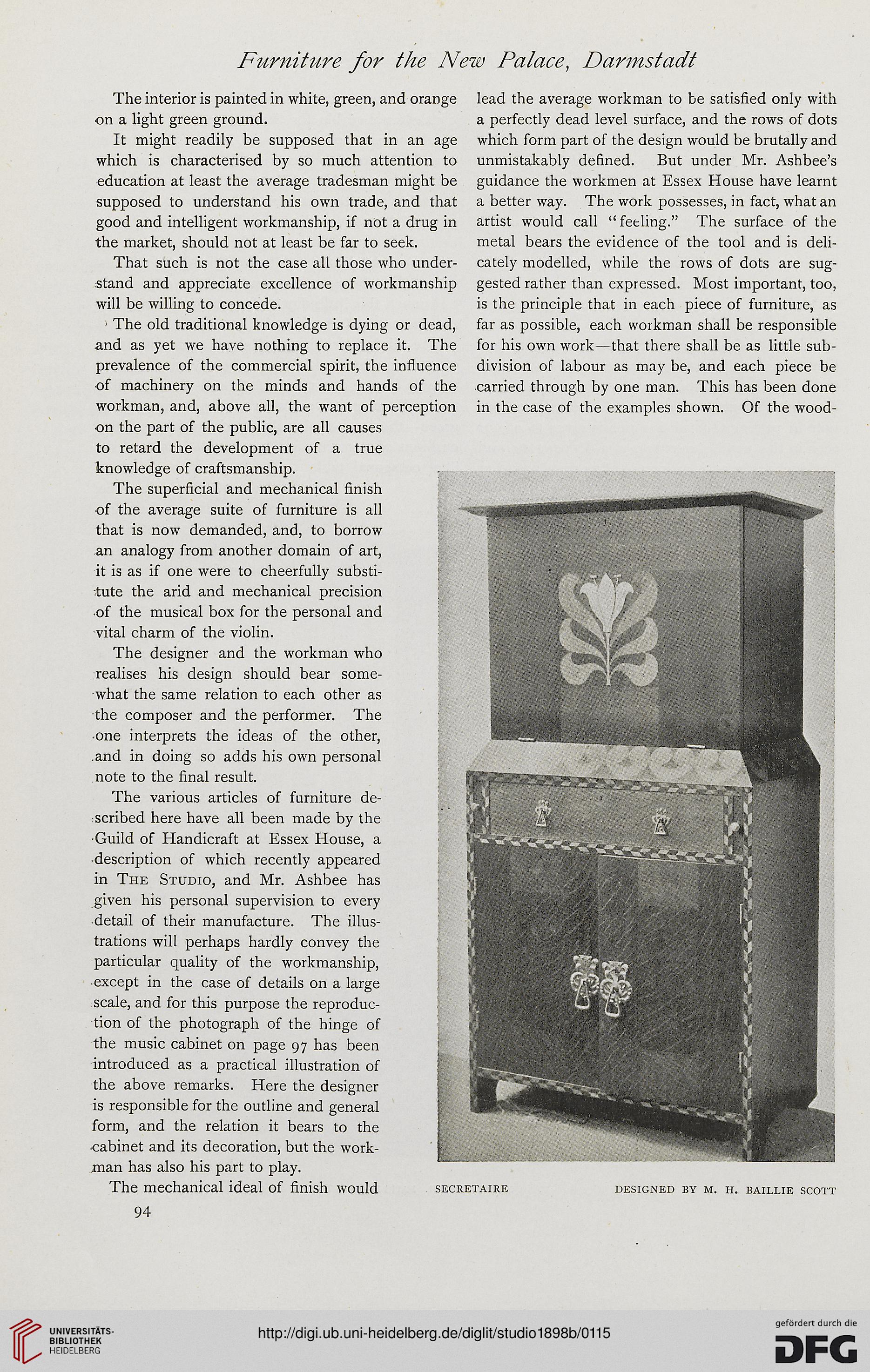

The various articles of furniture de-

scribed here have all been made by the

Guild of Handicraft at Essex House, a

description of which recently appeared

in The Studio, and Mr. Ashbee has

given his personal supervision to every

detail of their manufacture. The illus-

trations will perhaps hardly convey the

particular quality of the workmanship,

■except in the case of details on a large

scale, and for this purpose the reproduc-

tion of the photograph of the hinge of

the music cabinet on page 97 has been

introduced as a practical illustration of

the above remarks. Here the designer

is responsible for the outline and general

form, and the relation it bears to the

-cabinet and its decoration, but the work-

man has also his part to play.

The mechanical ideal of finish would secretaire designed by m. h. baillie scott

lead the average workman to be satisfied only with

a perfectly dead level surface, and the rows of dots

which form part of the design would be brutally and

unmistakably defined. But under Mr. Ashbee’s

guidance the workmen at Essex House have learnt

a better way. The work possesses, in fact, what an

artist would call “ feeling.” The surface of the

metal bears the evidence of the tool and is deli-

cately modelled, while the rows of dots are sug-

gested rather than expressed. Most important, too,

is the principle that in each piece of furniture, as

far as possible, each workman shall be responsible

for his own work—that there shall be as little sub-

division of labour as may be, and each piece be

carried through by one man. This has been done

in the case of the examples shown. Of the wood-

94

The interior is painted in white, green, and orange

on a light green ground.

It might readily be supposed that in an age

which is characterised by so much attention to

education at least the average tradesman might be

supposed to understand his own trade, and that

good and intelligent workmanship, if not a drug in

the market, should not at least be far to seek.

That such is not the case all those who under-

stand and appreciate excellence of workmanship

will be willing to concede.

The old traditional knowledge is dying or dead,

and as yet we have nothing to replace it. The

prevalence of the commercial spirit, the influence

of machinery on the minds and hands of the

workman, and, above all, the want of perception

on the part of the public, are all causes

to retard the development of a true

knowledge of craftsmanship.

The superficial and mechanical finish

of the average suite of furniture is all

that is now demanded, and, to borrow

an analogy from another domain of art,

it is as if one were to cheerfully substi-

tute the arid and mechanical precision

of the musical box for the personal and

vital charm of the violin.

The designer and the workman who

realises his design should bear some-

what the same relation to each other as

the composer and the performer. The

•one interprets the ideas of the other,

.and in doing so adds his own personal

note to the final result.

The various articles of furniture de-

scribed here have all been made by the

Guild of Handicraft at Essex House, a

description of which recently appeared

in The Studio, and Mr. Ashbee has

given his personal supervision to every

detail of their manufacture. The illus-

trations will perhaps hardly convey the

particular quality of the workmanship,

■except in the case of details on a large

scale, and for this purpose the reproduc-

tion of the photograph of the hinge of

the music cabinet on page 97 has been

introduced as a practical illustration of

the above remarks. Here the designer

is responsible for the outline and general

form, and the relation it bears to the

-cabinet and its decoration, but the work-

man has also his part to play.

The mechanical ideal of finish would secretaire designed by m. h. baillie scott

lead the average workman to be satisfied only with

a perfectly dead level surface, and the rows of dots

which form part of the design would be brutally and

unmistakably defined. But under Mr. Ashbee’s

guidance the workmen at Essex House have learnt

a better way. The work possesses, in fact, what an

artist would call “ feeling.” The surface of the

metal bears the evidence of the tool and is deli-

cately modelled, while the rows of dots are sug-

gested rather than expressed. Most important, too,

is the principle that in each piece of furniture, as

far as possible, each workman shall be responsible

for his own work—that there shall be as little sub-

division of labour as may be, and each piece be

carried through by one man. This has been done

in the case of the examples shown. Of the wood-

94