Tanagra Terra-cottas

Museum, at South Kensington, through the loans

of Mr. Salting and Sir Gibson Carmichael, and at

the Burlington Fine Arts Club, through its Exhibi-

tion in 1889, every opportunity has been afforded

of acquiring a thorough knowledge of the subject,

and yet the result is as just stated.

The remarkable side of the matter is this, that

no one with instincts for beauty, or interest in

antiquity, or in the evolution of art can fail to be

at once captivated by these terra-cottas. Mr. A.

Ionides, who is the fortunate possessor not only of

a house full of artistic creations, as readers of The

Studio of December last are well aware, but of

a remarkable collection of these statuettes, has

assured the writer that of all his beautiful things

none have so quickly appealed to all, no matter

how varied their tastes, as these groups and

figures, and concerning none has he been so ques-

tioned as to their origin, meaning, and use. May

be this ignorance is in the main due to the fact

that written information on the subject is but

scantily given in any English treatise on Greek

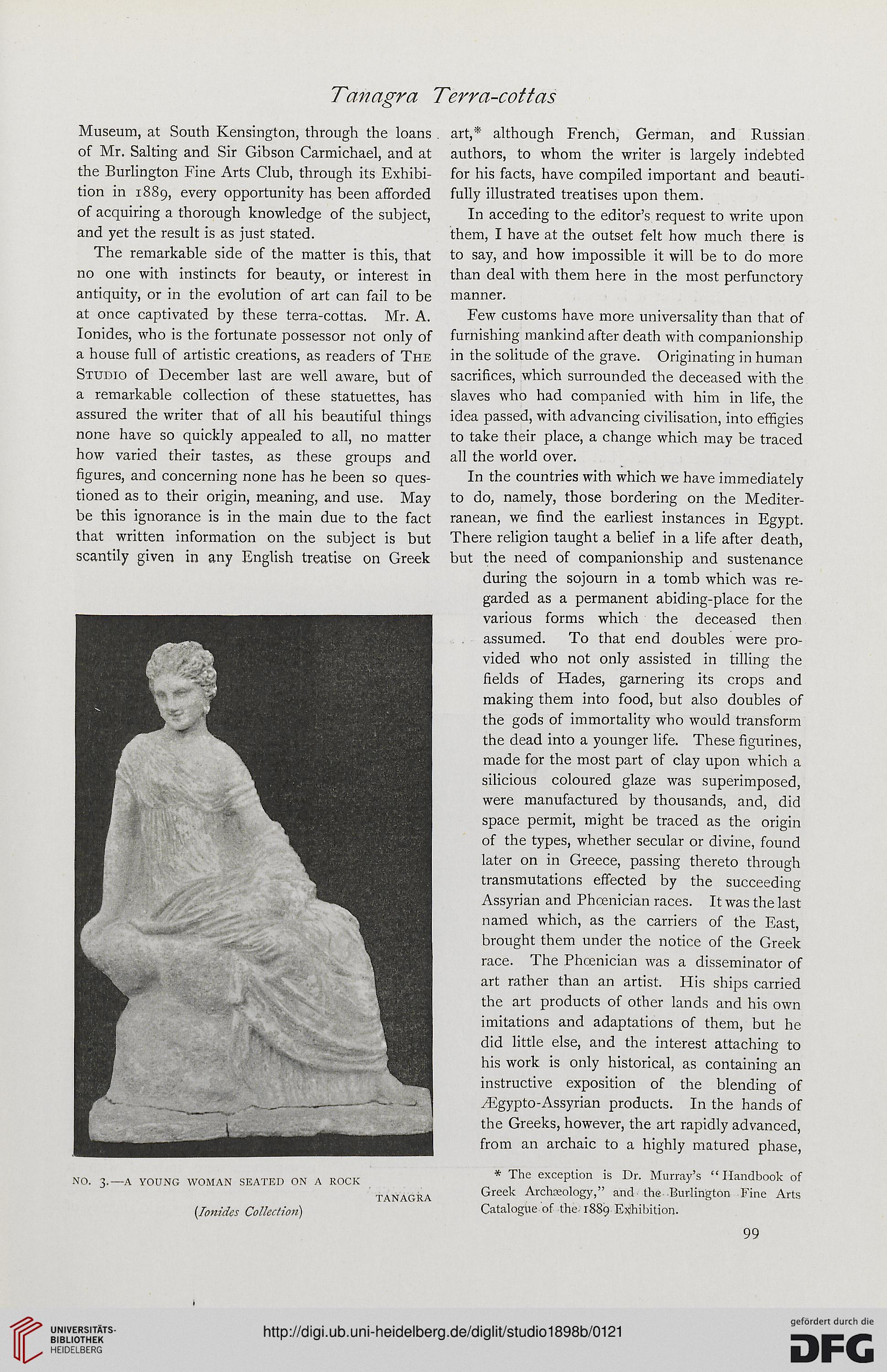

NO. 3.—A YOUNG WOMAN SEATED ON A ROCK

(Ionides Collection)

TANAGRA

art,'* although French, German, and Russian

authors, to whom the writer is largely indebted

for his facts, have compiled important and beauti-

fully illustrated treatises upon them.

In acceding to the editor’s request to write upon

them, I have at the outset felt how much there is

to say, and how impossible it will be to do more

than deal with them here in the most perfunctory

manner.

Few customs have more universality than that of

furnishing mankind after death with companionship

in the solitude of the grave. Originating in human

sacrifices, which surrounded the deceased with the

slaves who had companied with him in life, the

idea passed, with advancing civilisation, into effigies

to take their place, a change which may be traced

all the world over.

In the countries with which we have immediately

to do, namely, those bordering on the Mediter-

ranean, we find the earliest instances in Egypt.

There religion taught a belief in a life after death,

but the need of companionship and sustenance

during the sojourn in a tomb which was re-

garded as a permanent abiding-place for the

various forms which the deceased then

assumed. To that end doubles were pro-

vided who not only assisted in tilling the

fields of Hades, garnering its crops and

making them into food, but also doubles of

the gods of immortality who would transform

the dead into a younger life. These figurines,

made for the most part of clay upon which a

silicious coloured glaze was superimposed,

were manufactured by thousands, and, did

space permit, might be traced as the origin

of the types, whether secular or divine, found

later on in Greece, passing thereto through

transmutations effected by the succeeding

Assyrian and Phoenician races. It was the last

named which, as the carriers of the East,

brought them under the notice of the Greek

race. The Phoenician was a disseminator of

art rather than an artist. His ships carried

the art products of other lands and his own

imitations and adaptations of them, but he

did little else, and the interest attaching to

his work is only historical, as containing an

instructive exposition of the blending of

Aigypto-Assyrian products. In the hands of

the Greeks, however, the art rapidly advanced,

from an archaic to a highly matured phase,

* The exception is Dr. Murray’s “Handbook of

Greek Archaeology,” and the Burlington Fine Arts

Catalogue of the 1889 Exhibition.

99

Museum, at South Kensington, through the loans

of Mr. Salting and Sir Gibson Carmichael, and at

the Burlington Fine Arts Club, through its Exhibi-

tion in 1889, every opportunity has been afforded

of acquiring a thorough knowledge of the subject,

and yet the result is as just stated.

The remarkable side of the matter is this, that

no one with instincts for beauty, or interest in

antiquity, or in the evolution of art can fail to be

at once captivated by these terra-cottas. Mr. A.

Ionides, who is the fortunate possessor not only of

a house full of artistic creations, as readers of The

Studio of December last are well aware, but of

a remarkable collection of these statuettes, has

assured the writer that of all his beautiful things

none have so quickly appealed to all, no matter

how varied their tastes, as these groups and

figures, and concerning none has he been so ques-

tioned as to their origin, meaning, and use. May

be this ignorance is in the main due to the fact

that written information on the subject is but

scantily given in any English treatise on Greek

NO. 3.—A YOUNG WOMAN SEATED ON A ROCK

(Ionides Collection)

TANAGRA

art,'* although French, German, and Russian

authors, to whom the writer is largely indebted

for his facts, have compiled important and beauti-

fully illustrated treatises upon them.

In acceding to the editor’s request to write upon

them, I have at the outset felt how much there is

to say, and how impossible it will be to do more

than deal with them here in the most perfunctory

manner.

Few customs have more universality than that of

furnishing mankind after death with companionship

in the solitude of the grave. Originating in human

sacrifices, which surrounded the deceased with the

slaves who had companied with him in life, the

idea passed, with advancing civilisation, into effigies

to take their place, a change which may be traced

all the world over.

In the countries with which we have immediately

to do, namely, those bordering on the Mediter-

ranean, we find the earliest instances in Egypt.

There religion taught a belief in a life after death,

but the need of companionship and sustenance

during the sojourn in a tomb which was re-

garded as a permanent abiding-place for the

various forms which the deceased then

assumed. To that end doubles were pro-

vided who not only assisted in tilling the

fields of Hades, garnering its crops and

making them into food, but also doubles of

the gods of immortality who would transform

the dead into a younger life. These figurines,

made for the most part of clay upon which a

silicious coloured glaze was superimposed,

were manufactured by thousands, and, did

space permit, might be traced as the origin

of the types, whether secular or divine, found

later on in Greece, passing thereto through

transmutations effected by the succeeding

Assyrian and Phoenician races. It was the last

named which, as the carriers of the East,

brought them under the notice of the Greek

race. The Phoenician was a disseminator of

art rather than an artist. His ships carried

the art products of other lands and his own

imitations and adaptations of them, but he

did little else, and the interest attaching to

his work is only historical, as containing an

instructive exposition of the blending of

Aigypto-Assyrian products. In the hands of

the Greeks, however, the art rapidly advanced,

from an archaic to a highly matured phase,

* The exception is Dr. Murray’s “Handbook of

Greek Archaeology,” and the Burlington Fine Arts

Catalogue of the 1889 Exhibition.

99