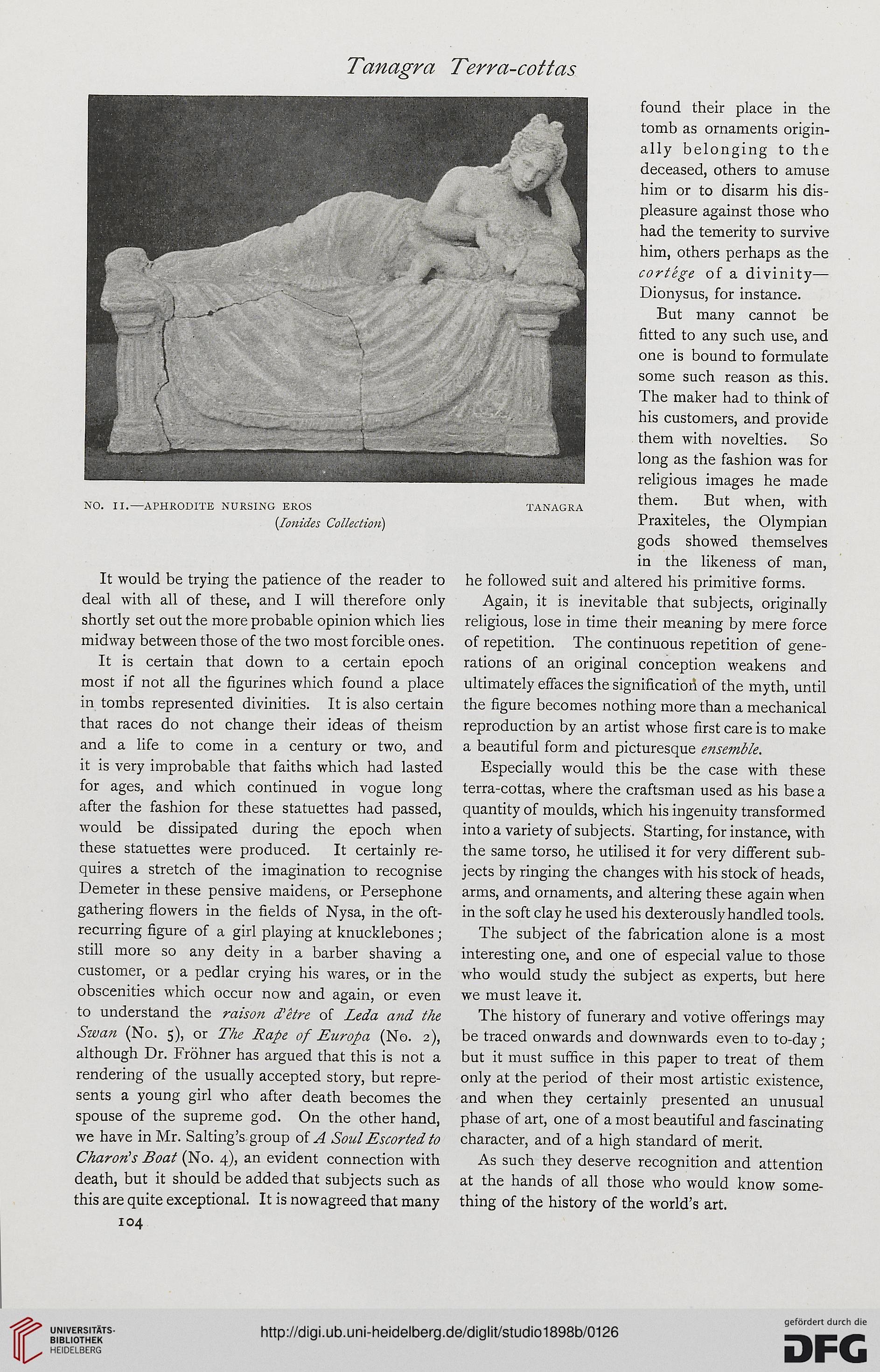

Tanagra Terra-cottas

It would be trying the patience of the reader to

deal with all of these, and I will therefore only

shortly set out the more probable opinion which lies

midway between those of the two most forcible ones.

It is certain that down to a certain epoch

most if not all the figurines which found a place

in tombs represented divinities. It is also certain

that races do not change their ideas of theism

and a life to come in a century or two, and

it is very improbable that faiths which had lasted

for ages, and which continued in vogue long

after the fashion for these statuettes had passed,

would be dissipated during the epoch when

these statuettes were produced. It certainly re-

quires a stretch of the imagination to recognise

Demeter in these pensive maidens, or Persephone

gathering flowers in the fields of Nysa, in the oft-

recurring figure of a girl playing at knucklebones;

still more so any deity in a barber shaving a

customer, or a pedlar crying his wares, or in the

obscenities which occur now and again, or even

to understand the raison d'etre of Leda and the

Swan (No. 5), or The Rape of Enropa (No. 2),

although Dr. Frohner has argued that this is not a

rendering of the usually accepted story, but repre-

sents a young girl who after death becomes the

spouse of the supreme god. On the other hand,

we have in Mr. Salting’s group of A Soul Escorted to

Charon's Boat (No. 4), an evident connection with

death, but it should be added that subjects such as

this are quite exceptional. It is now agreed that many

104

found their place in the

tomb as ornaments origin-

ally belonging to the

deceased, others to amuse

him or to disarm his dis-

pleasure against those who

had the temerity to survive

him, others perhaps as the

cortege of a divinity—

Dionysus, for instance.

But many cannot be

fitted to any such use, and

one is bound to formulate

some such reason as this.

The maker had to think of

his customers, and provide

them with novelties. So

long as the fashion was for

religious images he made

them. But when, with

Praxiteles, the Olympian

gods showed themselves

in the likeness of man,

he followed suit and altered his primitive forms.

Again, it is inevitable that subjects, originally

religious, lose in time their meaning by mere force

of repetition. The continuous repetition of gene-

rations of an original conception weakens and

ultimately effaces the significatiofi of the myth, until

the figure becomes nothing more than a mechanical

reproduction by an artist whose first care is to make

a beautiful form and picturesque ensemble.

Especially would this be the case with these

terra-cottas, where the craftsman used as his base a

quantity of moulds, which his ingenuity transformed

into a variety of subjects. Starting, for instance, with

the same torso, he utilised it for very different sub-

jects by ringing the changes with his stock of heads,

arms, and ornaments, and altering these again when

in the soft clay he used his dexterously handled tools.

The subject of the fabrication alone is a most

interesting one, and one of especial value to those

who would study the subject as experts, but here

we must leave it.

The history of funerary and votive offerings may

be traced onwards and downwards even to to-day;

but it must suffice in this paper to treat of them

only at the period of their most artistic existence,

and when they certainly presented an unusual

phase of art, one of a most beautiful and fascinating

character, and of a high standard of merit.

As such they deserve recognition and attention

at the hands of all those who would know some-

thing of the history of the world’s art.

It would be trying the patience of the reader to

deal with all of these, and I will therefore only

shortly set out the more probable opinion which lies

midway between those of the two most forcible ones.

It is certain that down to a certain epoch

most if not all the figurines which found a place

in tombs represented divinities. It is also certain

that races do not change their ideas of theism

and a life to come in a century or two, and

it is very improbable that faiths which had lasted

for ages, and which continued in vogue long

after the fashion for these statuettes had passed,

would be dissipated during the epoch when

these statuettes were produced. It certainly re-

quires a stretch of the imagination to recognise

Demeter in these pensive maidens, or Persephone

gathering flowers in the fields of Nysa, in the oft-

recurring figure of a girl playing at knucklebones;

still more so any deity in a barber shaving a

customer, or a pedlar crying his wares, or in the

obscenities which occur now and again, or even

to understand the raison d'etre of Leda and the

Swan (No. 5), or The Rape of Enropa (No. 2),

although Dr. Frohner has argued that this is not a

rendering of the usually accepted story, but repre-

sents a young girl who after death becomes the

spouse of the supreme god. On the other hand,

we have in Mr. Salting’s group of A Soul Escorted to

Charon's Boat (No. 4), an evident connection with

death, but it should be added that subjects such as

this are quite exceptional. It is now agreed that many

104

found their place in the

tomb as ornaments origin-

ally belonging to the

deceased, others to amuse

him or to disarm his dis-

pleasure against those who

had the temerity to survive

him, others perhaps as the

cortege of a divinity—

Dionysus, for instance.

But many cannot be

fitted to any such use, and

one is bound to formulate

some such reason as this.

The maker had to think of

his customers, and provide

them with novelties. So

long as the fashion was for

religious images he made

them. But when, with

Praxiteles, the Olympian

gods showed themselves

in the likeness of man,

he followed suit and altered his primitive forms.

Again, it is inevitable that subjects, originally

religious, lose in time their meaning by mere force

of repetition. The continuous repetition of gene-

rations of an original conception weakens and

ultimately effaces the significatiofi of the myth, until

the figure becomes nothing more than a mechanical

reproduction by an artist whose first care is to make

a beautiful form and picturesque ensemble.

Especially would this be the case with these

terra-cottas, where the craftsman used as his base a

quantity of moulds, which his ingenuity transformed

into a variety of subjects. Starting, for instance, with

the same torso, he utilised it for very different sub-

jects by ringing the changes with his stock of heads,

arms, and ornaments, and altering these again when

in the soft clay he used his dexterously handled tools.

The subject of the fabrication alone is a most

interesting one, and one of especial value to those

who would study the subject as experts, but here

we must leave it.

The history of funerary and votive offerings may

be traced onwards and downwards even to to-day;

but it must suffice in this paper to treat of them

only at the period of their most artistic existence,

and when they certainly presented an unusual

phase of art, one of a most beautiful and fascinating

character, and of a high standard of merit.

As such they deserve recognition and attention

at the hands of all those who would know some-

thing of the history of the world’s art.