Cast-Iron Work

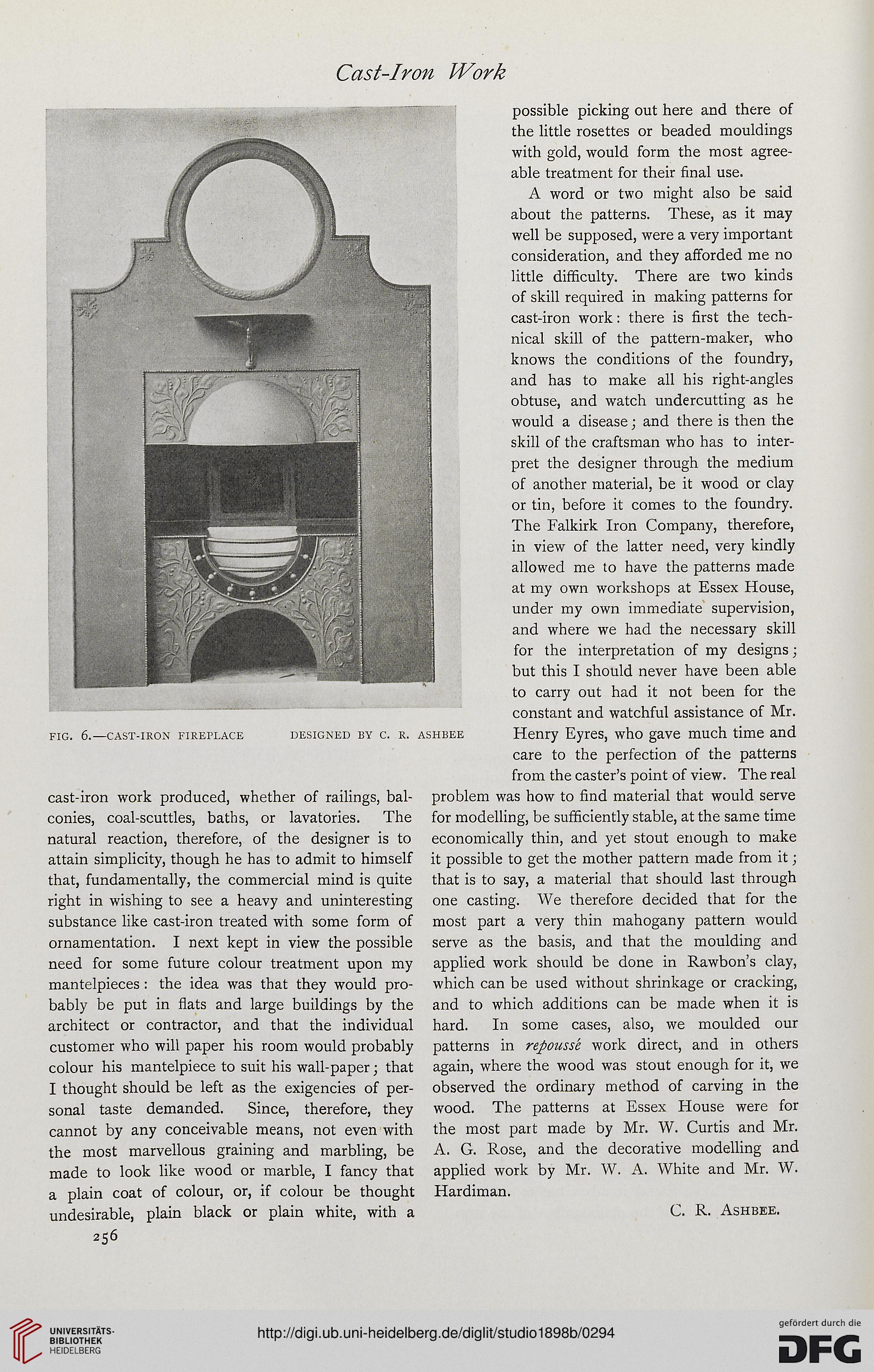

FIG. 6.—CAST-IRON FIREPLACE DESIGNED BY C. R. ASHBEE

cast-iron work produced, whether of railings, bal-

conies, coal-scuttles, baths, or lavatories. The

natural reaction, therefore, of the designer is to

attain simplicity, though he has to admit to himself

that, fundamentally, the commercial mind is quite

right in wishing to see a heavy and uninteresting

substance like cast-iron treated with some form of

ornamentation. I next kept in view the possible

need for some future colour treatment upon my

mantelpieces: the idea was that they would pro-

bably be put in flats and large buildings by the

architect or contractor, and that the individual

customer who will paper his room would probably

colour his mantelpiece to suit his wall-paper; that

I thought should be left as the exigencies of per-

sonal taste demanded. Since, therefore, they

cannot by any conceivable means, not even with

the most marvellous graining and marbling, be

made to look like wood or marble, I fancy that

a plain coat of colour, or, if colour be thought

undesirable, plain black or plain white, with a

256

possible picking out here and there of

the little rosettes or beaded mouldings

with gold, would form the most agree-

able treatment for their final use.

A word or two might also be said

about the patterns. These, as it may

well be supposed, were a very important

consideration, and they afforded me no

little difficulty. There are two kinds

of skill required in making patterns for

cast-iron work: there is first the tech-

nical skill of the pattern-maker, who

knows the conditions of the foundry,

and has to make all his right-angles

obtuse, and watch undercutting as he

would a disease; and there is then the

skill of the craftsman who has to inter-

pret the designer through the medium

of another material, be it wood or clay

or tin, before it comes to the foundry.

The Falkirk Iron Company, therefore,

in view of the latter need, very kindly

allowed me to have the patterns made

at my own workshops at Essex House,

under my own immediate supervision,

and where we had the necessary skill

for the interpretation of my designs;

but this I should never have been able

to carry out had it not been for the

constant and watchful assistance of Mr.

Henry Eyres, who gave much time and

care to the perfection of the patterns

from the caster’s point of view. The real

problem was how to find material that would serve

for modelling, be sufficiently stable, at the same time

economically thin, and yet stout enough to make

it possible to get the mother pattern made from it;

that is to say, a material that should last through

one casting. We therefore decided that for the

most part a very thin mahogany pattern would

serve as the basis, and that the moulding and

applied work should be done in Rawbon’s clay,

which can be used without shrinkage or cracking,

and to which additions can be made when it is

hard. In some cases, also, we moulded our

patterns in repousse work direct, and in others

again, where the wood was stout enough for it, we

observed the ordinary method of carving in the

wood. The patterns at Essex House were for

the most part made by Mr. W. Curtis and Mr.

A. G. Rose, and the decorative modelling and

applied work by Mr. W. A. White and Mr. W.

Hardiman.

C. R. Ashbee.

FIG. 6.—CAST-IRON FIREPLACE DESIGNED BY C. R. ASHBEE

cast-iron work produced, whether of railings, bal-

conies, coal-scuttles, baths, or lavatories. The

natural reaction, therefore, of the designer is to

attain simplicity, though he has to admit to himself

that, fundamentally, the commercial mind is quite

right in wishing to see a heavy and uninteresting

substance like cast-iron treated with some form of

ornamentation. I next kept in view the possible

need for some future colour treatment upon my

mantelpieces: the idea was that they would pro-

bably be put in flats and large buildings by the

architect or contractor, and that the individual

customer who will paper his room would probably

colour his mantelpiece to suit his wall-paper; that

I thought should be left as the exigencies of per-

sonal taste demanded. Since, therefore, they

cannot by any conceivable means, not even with

the most marvellous graining and marbling, be

made to look like wood or marble, I fancy that

a plain coat of colour, or, if colour be thought

undesirable, plain black or plain white, with a

256

possible picking out here and there of

the little rosettes or beaded mouldings

with gold, would form the most agree-

able treatment for their final use.

A word or two might also be said

about the patterns. These, as it may

well be supposed, were a very important

consideration, and they afforded me no

little difficulty. There are two kinds

of skill required in making patterns for

cast-iron work: there is first the tech-

nical skill of the pattern-maker, who

knows the conditions of the foundry,

and has to make all his right-angles

obtuse, and watch undercutting as he

would a disease; and there is then the

skill of the craftsman who has to inter-

pret the designer through the medium

of another material, be it wood or clay

or tin, before it comes to the foundry.

The Falkirk Iron Company, therefore,

in view of the latter need, very kindly

allowed me to have the patterns made

at my own workshops at Essex House,

under my own immediate supervision,

and where we had the necessary skill

for the interpretation of my designs;

but this I should never have been able

to carry out had it not been for the

constant and watchful assistance of Mr.

Henry Eyres, who gave much time and

care to the perfection of the patterns

from the caster’s point of view. The real

problem was how to find material that would serve

for modelling, be sufficiently stable, at the same time

economically thin, and yet stout enough to make

it possible to get the mother pattern made from it;

that is to say, a material that should last through

one casting. We therefore decided that for the

most part a very thin mahogany pattern would

serve as the basis, and that the moulding and

applied work should be done in Rawbon’s clay,

which can be used without shrinkage or cracking,

and to which additions can be made when it is

hard. In some cases, also, we moulded our

patterns in repousse work direct, and in others

again, where the wood was stout enough for it, we

observed the ordinary method of carving in the

wood. The patterns at Essex House were for

the most part made by Mr. W. Curtis and Mr.

A. G. Rose, and the decorative modelling and

applied work by Mr. W. A. White and Mr. W.

Hardiman.

C. R. Ashbee.