A Dutch Etcher

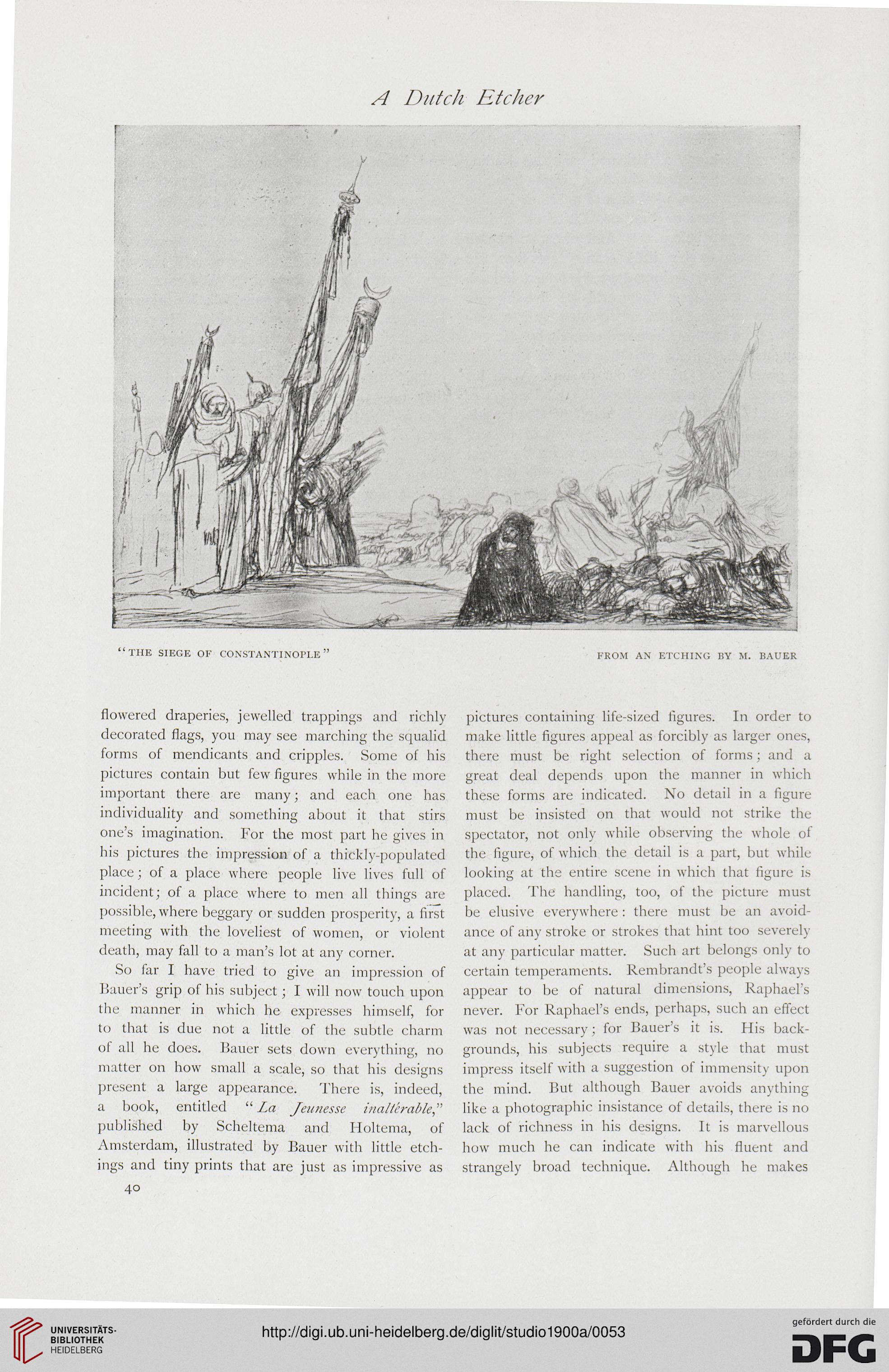

flowered draperies, jewelled trappings and richly

decorated flags, you may see marching the squalid

forms of mendicants and cripples. Some of his

pictures contain but few figures while in the more

important there are many; and each one has

individuality and something about it that stirs

one's imagination. For the most part he gives in

his pictures the impression of a thickly-populated

place; of a place where people live lives full of

incident; of a place where to men all things are

possible, where beggary or sudden prosperity, a first

meeting with the loveliest of women, or violent

death, may fall to a man's lot at any corner.

So far I have tried to give an impression of

Bauer's grip of his subject; I will now touch upon

the manner in which he expresses himself, for

to that is due not a little of the subtle charm

of all he does. Bauer sets down everything, no

matter on how small a scale, so that his designs

present a large appearance. There is, indeed,

a book, entitled " La Jeunesse inalterable"

published by Scheltema and Holtema, of

Amsterdam, illustrated by Bauer with little etch-

ings and tiny prints that are just as impressive as

40

pictures containing life-sized figures. In order to

make little figures appeal as forcibly as larger ones,

there must be right selection of forms; and a

great deal depends upon the manner in which

these forms are indicated. No detail in a figure

must be insisted on that would not strike the

spectator, not only while observing the whole of

the figure, of which the detail is a part, but while

looking at the entire scene in which that figure is

placed. The handling, too, of the picture must

be elusive everywhere : there must be an avoid-

ance of any stroke or strokes that hint too severely

at any particular matter. Such art belongs only to

certain temperaments. Rembrandt's people always

appear to be of natural dimensions, Raphael's

never. For Raphael's ends, perhaps, such an effect

was not necessary; for Bauer's it is. His back-

grounds, his subjects require a style that must

impress itself with a suggestion of immensity upon

the mind. But although Bauer avoids anything

like a photographic insistance of details, there is no

lack of richness in his designs. It is marvellous

how much he can indicate with his fluent and

strangely broad technique. Although he makes

flowered draperies, jewelled trappings and richly

decorated flags, you may see marching the squalid

forms of mendicants and cripples. Some of his

pictures contain but few figures while in the more

important there are many; and each one has

individuality and something about it that stirs

one's imagination. For the most part he gives in

his pictures the impression of a thickly-populated

place; of a place where people live lives full of

incident; of a place where to men all things are

possible, where beggary or sudden prosperity, a first

meeting with the loveliest of women, or violent

death, may fall to a man's lot at any corner.

So far I have tried to give an impression of

Bauer's grip of his subject; I will now touch upon

the manner in which he expresses himself, for

to that is due not a little of the subtle charm

of all he does. Bauer sets down everything, no

matter on how small a scale, so that his designs

present a large appearance. There is, indeed,

a book, entitled " La Jeunesse inalterable"

published by Scheltema and Holtema, of

Amsterdam, illustrated by Bauer with little etch-

ings and tiny prints that are just as impressive as

40

pictures containing life-sized figures. In order to

make little figures appeal as forcibly as larger ones,

there must be right selection of forms; and a

great deal depends upon the manner in which

these forms are indicated. No detail in a figure

must be insisted on that would not strike the

spectator, not only while observing the whole of

the figure, of which the detail is a part, but while

looking at the entire scene in which that figure is

placed. The handling, too, of the picture must

be elusive everywhere : there must be an avoid-

ance of any stroke or strokes that hint too severely

at any particular matter. Such art belongs only to

certain temperaments. Rembrandt's people always

appear to be of natural dimensions, Raphael's

never. For Raphael's ends, perhaps, such an effect

was not necessary; for Bauer's it is. His back-

grounds, his subjects require a style that must

impress itself with a suggestion of immensity upon

the mind. But although Bauer avoids anything

like a photographic insistance of details, there is no

lack of richness in his designs. It is marvellous

how much he can indicate with his fluent and

strangely broad technique. Although he makes