Stttciio- Talk

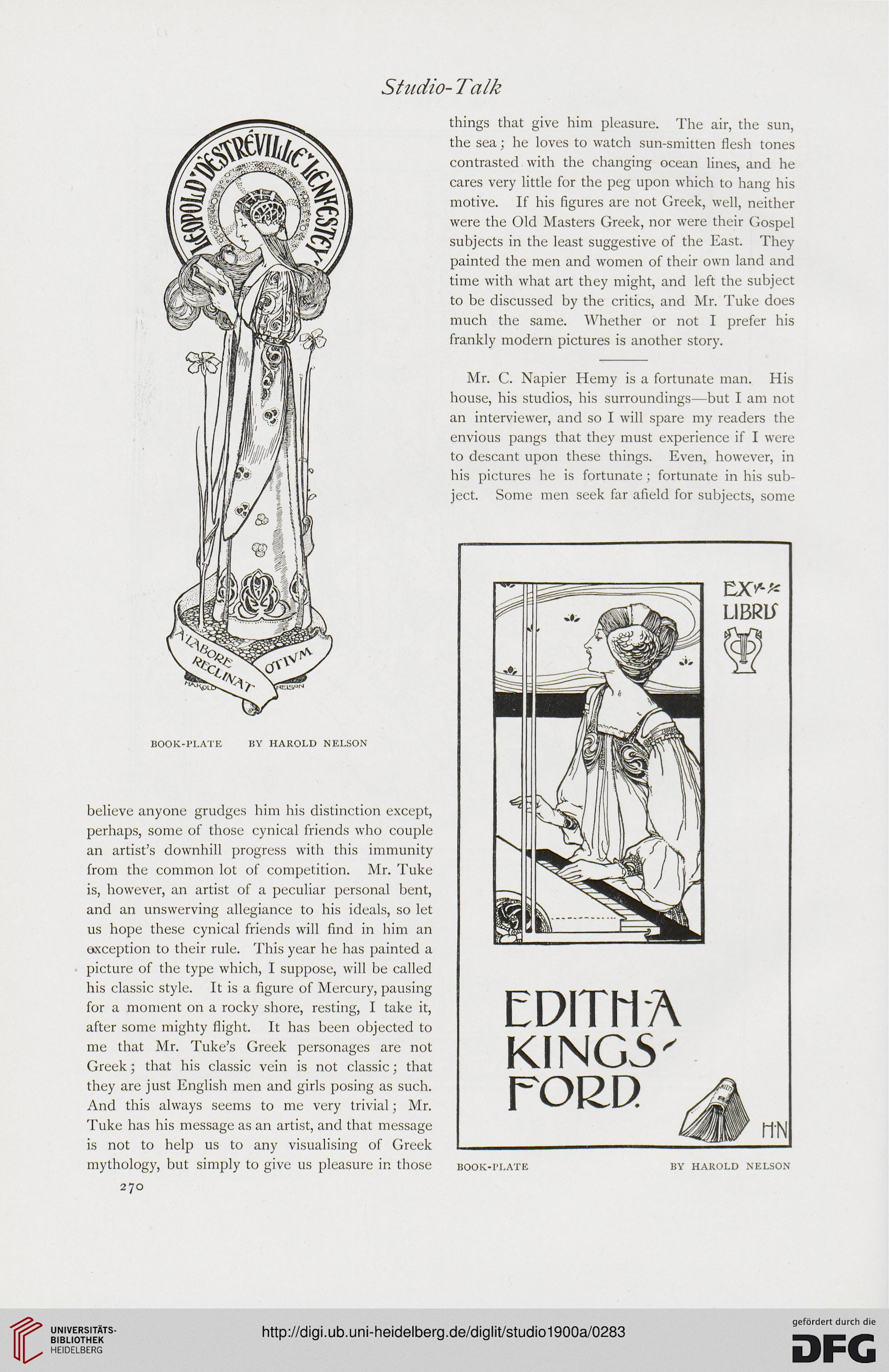

BOOK-PLATE BY HAROLD NELSON

believe anyone grudges him his distinction except,

perhaps, some of those cynical friends who couple

an artist's downhill progress with this immunity

from the common lot of competition. Mr. Tuke

is, however, an artist of a peculiar personal bent,

and an unswerving allegiance to his ideals, so let

us hope these cynical friends will find in him an

exception to their rule. This year he has painted a

picture of the type which, I suppose, will be called

his classic style. It is a figure of Mercury, pausing

for a moment on a rocky shore, resting, I take it,

after some mighty flight. It has been objected to

me that Mr. Tuke's Greek personages are not

Greek; that his classic vein is not classic; that

they are just English men and girls posing as such.

And this always seems to me very trivial; Mr.

Tuke has his message as an artist, and that message

is not to help us to any visualising of Greek

mythology, but simply to give us pleasure in those

270

things that give him pleasure. The air, the sun,

the sea; he loves to watch sun-smitten flesh tones

contrasted with the changing ocean lines, and he

cares very little for the peg upon which to hang his

motive. If his figures are not Greek, well, neither

were the Old Masters Greek, nor were their Gospel

subjects in the least suggestive of the East. They

painted the men and women of their own land and

time with what art they might, and left the subject

to be discussed by the critics, and Mr. Tuke does

much the same. Whether or not I prefer his

frankly modern pictures is another story.

Mr. C. Napier Hemy is a fortunate man. His

house, his studios, his surroundings—but I am not

an interviewer, and so I will spare my readers the

envious pangs that they must experience if I were

to descant upon these things. Even, however, in

his pictures he is fortunate ; fortunate in his sub-

ject. Some men seek far afield for subjects, some

BOOK-PLATE BY HAROLD NELSON

EDITH A

KING5'

FORD. ^

BOOK-PLATE BY HAROLD NELSON

believe anyone grudges him his distinction except,

perhaps, some of those cynical friends who couple

an artist's downhill progress with this immunity

from the common lot of competition. Mr. Tuke

is, however, an artist of a peculiar personal bent,

and an unswerving allegiance to his ideals, so let

us hope these cynical friends will find in him an

exception to their rule. This year he has painted a

picture of the type which, I suppose, will be called

his classic style. It is a figure of Mercury, pausing

for a moment on a rocky shore, resting, I take it,

after some mighty flight. It has been objected to

me that Mr. Tuke's Greek personages are not

Greek; that his classic vein is not classic; that

they are just English men and girls posing as such.

And this always seems to me very trivial; Mr.

Tuke has his message as an artist, and that message

is not to help us to any visualising of Greek

mythology, but simply to give us pleasure in those

270

things that give him pleasure. The air, the sun,

the sea; he loves to watch sun-smitten flesh tones

contrasted with the changing ocean lines, and he

cares very little for the peg upon which to hang his

motive. If his figures are not Greek, well, neither

were the Old Masters Greek, nor were their Gospel

subjects in the least suggestive of the East. They

painted the men and women of their own land and

time with what art they might, and left the subject

to be discussed by the critics, and Mr. Tuke does

much the same. Whether or not I prefer his

frankly modern pictures is another story.

Mr. C. Napier Hemy is a fortunate man. His

house, his studios, his surroundings—but I am not

an interviewer, and so I will spare my readers the

envious pangs that they must experience if I were

to descant upon these things. Even, however, in

his pictures he is fortunate ; fortunate in his sub-

ject. Some men seek far afield for subjects, some

BOOK-PLATE BY HAROLD NELSON

EDITH A

KING5'

FORD. ^