HIRST WALKER, R.B.A. 0 a

ENGLISH artistic genius may, very

broadly, be divided into two main

types—the literal-representational and the

intuitive-allegorical. Sir Joshua Reynolds

was a supreme example of the first type

and William Blake of the second. Both

types have their spheres of excellence, but

when either attempts to invade the other's

province results are apt to be disastrous.

If William Blake ever attempted literal

representation the error is forgotten. Sir

Joshua, however, made attempts at al-

legory. Because he lacked the requisite

intuitional power, the results were so banal

that subsequent generations, somewhat

unreasonably, took fright at all allegorical

painting. The representational mind sees

objects in their material form, and, being

undisturbed by other considerations, sees

them clearly. The intuitional mind may

see objects less precisely than the other,

but is alive to all the mystic but important

significances and relationships which go

to make up that strange dream, our life.

Within these two main streams all sorts

of diversities and modifications occur.

II y a fagots et fagots. Thus, whilst the

work of Hirst Walker is in no sense

fathered by the work of Blake, he is on

Blake's side of the main division. He is

a painter, not of objects as objects, but of

visions expounded by forms. Possibly

this sort of art is less easily comprehended

by the lay mind than work of which we

can say " Isn't it just done to the life i "

with smug satisfaction at having recog-

nised what we are accustomed to. An

American wit said recently, " Ideals are

funny little things : they won't work unless

you do," and this applies to idealistic art.

It requires the effort of comprehension

from the beholder, a 0 a 0

From what motives does such an artist

work id a a a a a

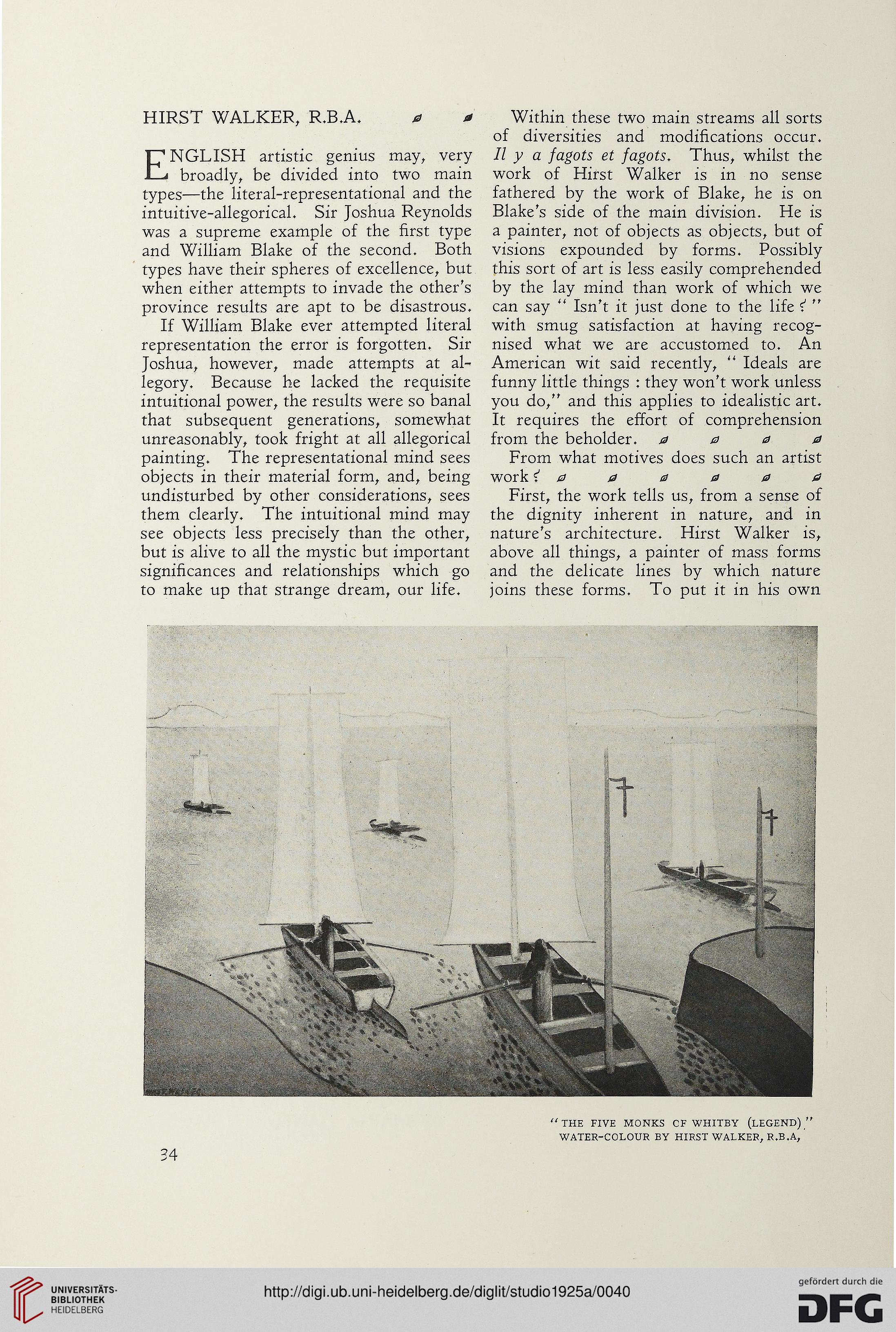

First, the work tells us, from a sense of

the dignity inherent in nature, and in

nature's architecture. Hirst Walker is,

above all things, a painter of mass forms

and the delicate lines by which nature

joins these forms. To put it in his own

ENGLISH artistic genius may, very

broadly, be divided into two main

types—the literal-representational and the

intuitive-allegorical. Sir Joshua Reynolds

was a supreme example of the first type

and William Blake of the second. Both

types have their spheres of excellence, but

when either attempts to invade the other's

province results are apt to be disastrous.

If William Blake ever attempted literal

representation the error is forgotten. Sir

Joshua, however, made attempts at al-

legory. Because he lacked the requisite

intuitional power, the results were so banal

that subsequent generations, somewhat

unreasonably, took fright at all allegorical

painting. The representational mind sees

objects in their material form, and, being

undisturbed by other considerations, sees

them clearly. The intuitional mind may

see objects less precisely than the other,

but is alive to all the mystic but important

significances and relationships which go

to make up that strange dream, our life.

Within these two main streams all sorts

of diversities and modifications occur.

II y a fagots et fagots. Thus, whilst the

work of Hirst Walker is in no sense

fathered by the work of Blake, he is on

Blake's side of the main division. He is

a painter, not of objects as objects, but of

visions expounded by forms. Possibly

this sort of art is less easily comprehended

by the lay mind than work of which we

can say " Isn't it just done to the life i "

with smug satisfaction at having recog-

nised what we are accustomed to. An

American wit said recently, " Ideals are

funny little things : they won't work unless

you do," and this applies to idealistic art.

It requires the effort of comprehension

from the beholder, a 0 a 0

From what motives does such an artist

work id a a a a a

First, the work tells us, from a sense of

the dignity inherent in nature, and in

nature's architecture. Hirst Walker is,

above all things, a painter of mass forms

and the delicate lines by which nature

joins these forms. To put it in his own