A Spanish PVriting Book

laymen, and brought with it a demand for books of

fair copies and rules for their use.

Without spending more time on this part of the

subject, we may say in passing therefrom that so

early as 1514, Sigismondo dei Fanti published a

writing-book at Rome of which the examples were

cut by Ugo da Carpi; that in 1529 appeared the

famous philosophy of writing by Geoffrey Tory at

Paris; and in 1548 at Saragossa the first edition of

Juan de Yciar's Rccopilacion Subtilissima, a very

beautiful work, but one rarely seen in perfect con-

dition. On the model of this latter master is

founded the Arte de Escrivir of Francisco Lucas

(Madrid, 1577, the blocks dated 1570), which

forms the subject of the present paper.

The book begins with much parade of royal

licence, of dedication, of gratulatory verse addressed

to the author; but this once over, our master

plunges directly into his subject with useful disser-

tation on the different styles of lettering in use, the

manner of holding the pen, and " other matters

necessary and convenient." Of this pen-holding,

we may shortly say that he advocates, not the rigid,

uncomfortable method many of us were taught at

school, with unbent fingers and stiffened thumb;

but an easy grasp of the barrel between thumb and

48

fingers, the points of which come nearly opposite

to each other. A little practice will realise this

position much more easily than pages of instruc-

tion, when it is remembered that the pen is a reed

or quill cut to a fairly broad point; and that the

thick and thin strokes of the writing are to produce

themselves naturally with the swing of the hand.

It becomes convenient in this connection, also to

point out the essential difference between the old

and the new methods of writing ; in the latter thick

or thin strokes are the result, to a considerable

extent, of variations in the pressure put upon the

nib—a practice provocative of the maximum of

friction between pen and paper and only effective

of an artificial line; while in the former these

differences of strength are the easy consequence of

the angle which the point of the quill or reed makes

with its line of general progression.

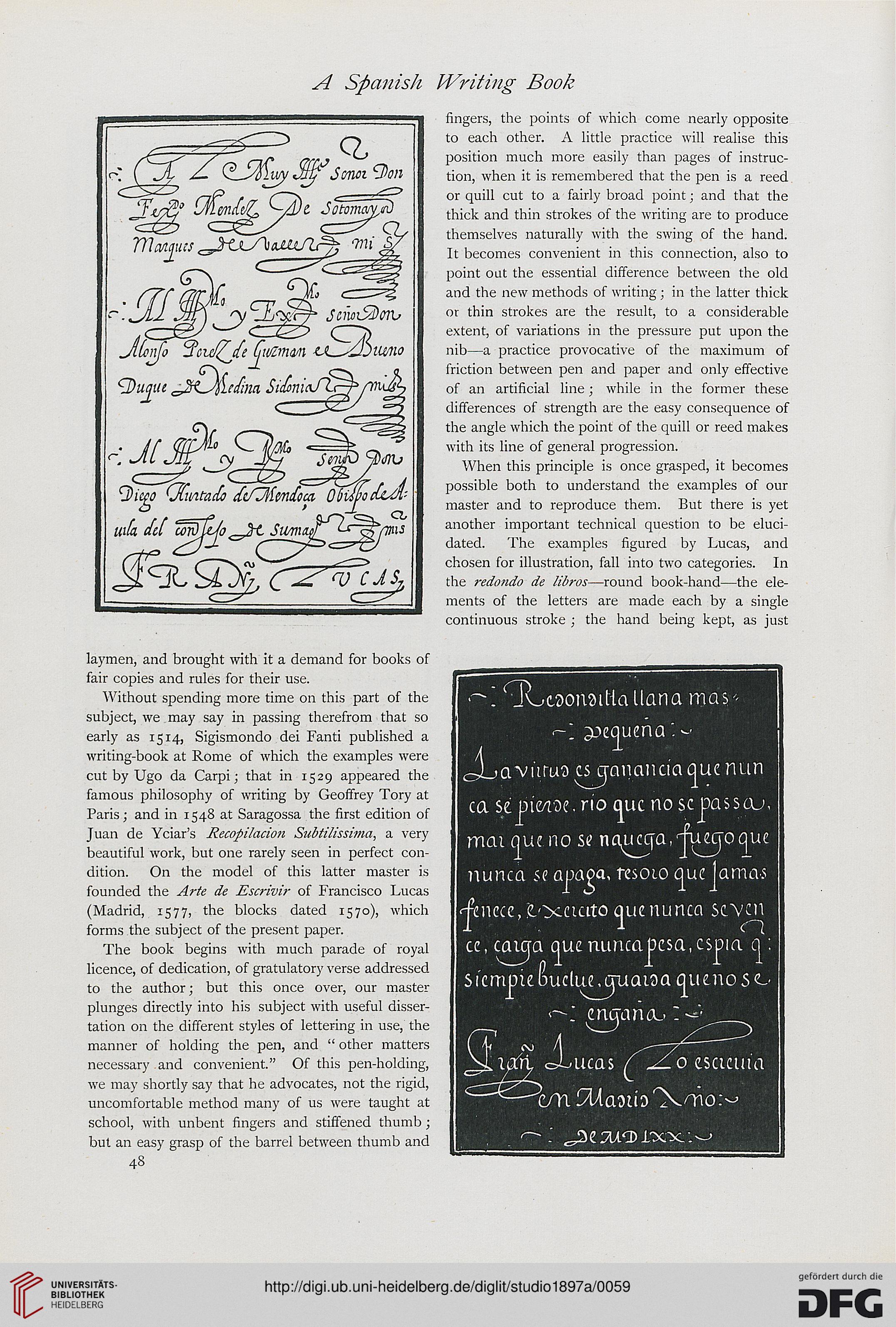

When this principle is once grasped, it becomes

possible both to understand the examples of our

master and to reproduce them. But there is yet

another important technical question to be eluci-

dated. The examples figured by Lucas, and

chosen for illustration, fall into two categories. In

the redondo de libros—round book-hand—the ele-

ments of the letters are made each by a single

continuous stroke ; the hand being kept, as just

n^eaonaitialiana mas--

<~\ joecjuena'-

cljavitruo csjjauantiacjue nun

ca sepie/i'De.rt'o cjuc noscpassaj,

mai aue no se naj^a, J^uejoque

nunca $.? apaga, resoio Cjue Jamas

sjcmcz, l-yiaato <jue nunca sc\en

cc, caicja quenuncajpcsa,cspia cj:

s i'c mpi e 6u c lue^ju aia a cju t n o 5 C

<-*-* encjanoL-

ucas (_ csactita

- .'.CJae5ua>i,xx.:>-'

laymen, and brought with it a demand for books of

fair copies and rules for their use.

Without spending more time on this part of the

subject, we may say in passing therefrom that so

early as 1514, Sigismondo dei Fanti published a

writing-book at Rome of which the examples were

cut by Ugo da Carpi; that in 1529 appeared the

famous philosophy of writing by Geoffrey Tory at

Paris; and in 1548 at Saragossa the first edition of

Juan de Yciar's Rccopilacion Subtilissima, a very

beautiful work, but one rarely seen in perfect con-

dition. On the model of this latter master is

founded the Arte de Escrivir of Francisco Lucas

(Madrid, 1577, the blocks dated 1570), which

forms the subject of the present paper.

The book begins with much parade of royal

licence, of dedication, of gratulatory verse addressed

to the author; but this once over, our master

plunges directly into his subject with useful disser-

tation on the different styles of lettering in use, the

manner of holding the pen, and " other matters

necessary and convenient." Of this pen-holding,

we may shortly say that he advocates, not the rigid,

uncomfortable method many of us were taught at

school, with unbent fingers and stiffened thumb;

but an easy grasp of the barrel between thumb and

48

fingers, the points of which come nearly opposite

to each other. A little practice will realise this

position much more easily than pages of instruc-

tion, when it is remembered that the pen is a reed

or quill cut to a fairly broad point; and that the

thick and thin strokes of the writing are to produce

themselves naturally with the swing of the hand.

It becomes convenient in this connection, also to

point out the essential difference between the old

and the new methods of writing ; in the latter thick

or thin strokes are the result, to a considerable

extent, of variations in the pressure put upon the

nib—a practice provocative of the maximum of

friction between pen and paper and only effective

of an artificial line; while in the former these

differences of strength are the easy consequence of

the angle which the point of the quill or reed makes

with its line of general progression.

When this principle is once grasped, it becomes

possible both to understand the examples of our

master and to reproduce them. But there is yet

another important technical question to be eluci-

dated. The examples figured by Lucas, and

chosen for illustration, fall into two categories. In

the redondo de libros—round book-hand—the ele-

ments of the letters are made each by a single

continuous stroke ; the hand being kept, as just

n^eaonaitialiana mas--

<~\ joecjuena'-

cljavitruo csjjauantiacjue nun

ca sepie/i'De.rt'o cjuc noscpassaj,

mai aue no se naj^a, J^uejoque

nunca $.? apaga, resoio Cjue Jamas

sjcmcz, l-yiaato <jue nunca sc\en

cc, caicja quenuncajpcsa,cspia cj:

s i'c mpi e 6u c lue^ju aia a cju t n o 5 C

<-*-* encjanoL-

ucas (_ csactita

- .'.CJae5ua>i,xx.:>-'