Long Case Clocks

us has not, as a child, surreptitiously opened the

door of the case to gaze on the weights or to watch

the swing of the pendulum. The pendulum is

really the essence of the whole thing, for the long

case was brought into existence by the invention

of mechanism which allowed so long a pendulum

to swing in so confined a space.

Long case clocks have as a rule been very badly

treated by artists. For a single faithful representa-

tion of an existing specimen one may find twenty

pictures where features of different periods have

been introduced into the same timekeeper. This

generally occurs probably through the painter of

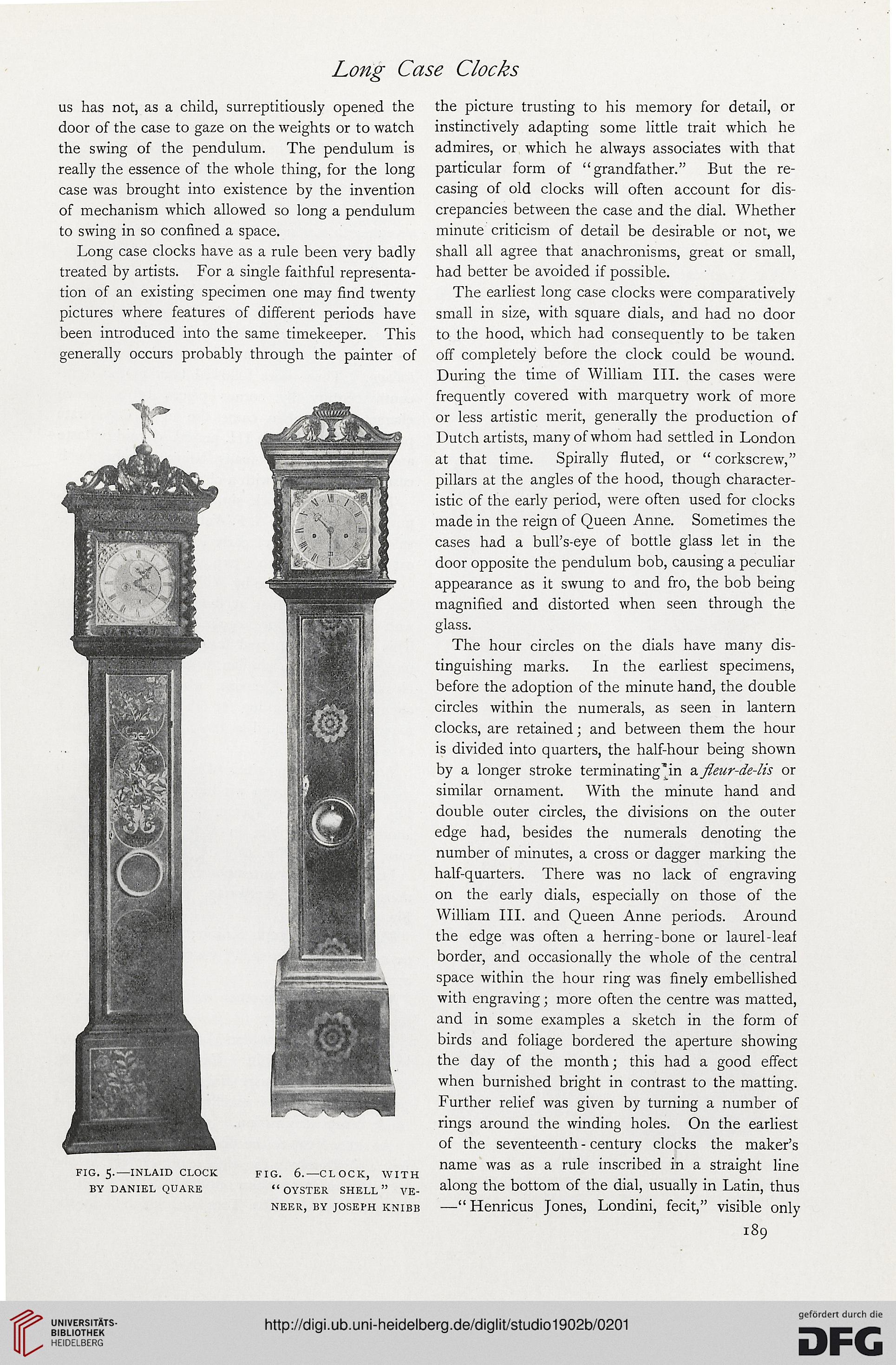

FIG. 5.—INLAID CLOCK FIG. 6.—CLOCK, WITH

BY DANIEL QUARE "OYSTER SHELL" VE-

NEER, BY JOSEPH KNIBB

the picture trusting to his memory for detail, or

instinctively adapting some little trait which he

admires, or which he always associates with that

particular form of "grandfather." But the re-

casing of old clocks will often account for dis-

crepancies between the case and the dial. Whether

minute criticism of detail be desirable or not, we

shall all agree that anachronisms, great or small,

had better be avoided if possible.

The earliest long case clocks were comparatively

small in size, with square dials, and had no door

to the hood, which had consequently to be taken

off completely before the clock could be wound.

During the time of William III. the cases were

frequently covered with marquetry work of more

or less artistic merit, generally the production of

Dutch artists, many of whom had settled in London

at that time. Spirally fluted, or " corkscrew,"

pillars at the angles of the hood, though character-

istic of the early period, were often used for clocks

made in the reign of Queen Anne. Sometimes the

cases had a bull's-eye of bottle glass let in the

door opposite the pendulum bob, causing a peculiar

appearance as it swung to and fro, the bob being

magnified and distorted when seen through the

glass.

The hour circles on the dials have many dis-

tinguishing marks. In the earliest specimens,

before the adoption of the minute hand, the double

circles within the numerals, as seen in lantern

clocks, are retained; and between them the hour

is divided into quarters, the half-hour being shown

by a longer stroke terminating'in a fleur-de-lis or

similar ornament. With the minute hand and

double outer circles, the divisions on the outer

edge had, besides the numerals denoting the

number of minutes, a cross or dagger marking the

half-quarters. There was no lack of engraving

on the early dials, especially on those of the

William III. and Queen Anne periods. Around

the edge was often a herring-bone or laurel-leaf

border, and occasionally the whole of the central

space within the hour ring was finely embellished

with engraving; more often the centre was matted,

and in some examples a sketch in the form of

birds and foliage bordered the aperture showing

the day of the month; this had a good effect

when burnished bright in contrast to the matting.

Further relief was given by turning a number of

rings around the winding holes. On the earliest

of the seventeenth - century clocks the maker's

name was as a rule inscribed in a straight line

along the bottom of the dial, usually in Latin, thus

—"Henricus Jones, Londini, fecit," visible only

189

us has not, as a child, surreptitiously opened the

door of the case to gaze on the weights or to watch

the swing of the pendulum. The pendulum is

really the essence of the whole thing, for the long

case was brought into existence by the invention

of mechanism which allowed so long a pendulum

to swing in so confined a space.

Long case clocks have as a rule been very badly

treated by artists. For a single faithful representa-

tion of an existing specimen one may find twenty

pictures where features of different periods have

been introduced into the same timekeeper. This

generally occurs probably through the painter of

FIG. 5.—INLAID CLOCK FIG. 6.—CLOCK, WITH

BY DANIEL QUARE "OYSTER SHELL" VE-

NEER, BY JOSEPH KNIBB

the picture trusting to his memory for detail, or

instinctively adapting some little trait which he

admires, or which he always associates with that

particular form of "grandfather." But the re-

casing of old clocks will often account for dis-

crepancies between the case and the dial. Whether

minute criticism of detail be desirable or not, we

shall all agree that anachronisms, great or small,

had better be avoided if possible.

The earliest long case clocks were comparatively

small in size, with square dials, and had no door

to the hood, which had consequently to be taken

off completely before the clock could be wound.

During the time of William III. the cases were

frequently covered with marquetry work of more

or less artistic merit, generally the production of

Dutch artists, many of whom had settled in London

at that time. Spirally fluted, or " corkscrew,"

pillars at the angles of the hood, though character-

istic of the early period, were often used for clocks

made in the reign of Queen Anne. Sometimes the

cases had a bull's-eye of bottle glass let in the

door opposite the pendulum bob, causing a peculiar

appearance as it swung to and fro, the bob being

magnified and distorted when seen through the

glass.

The hour circles on the dials have many dis-

tinguishing marks. In the earliest specimens,

before the adoption of the minute hand, the double

circles within the numerals, as seen in lantern

clocks, are retained; and between them the hour

is divided into quarters, the half-hour being shown

by a longer stroke terminating'in a fleur-de-lis or

similar ornament. With the minute hand and

double outer circles, the divisions on the outer

edge had, besides the numerals denoting the

number of minutes, a cross or dagger marking the

half-quarters. There was no lack of engraving

on the early dials, especially on those of the

William III. and Queen Anne periods. Around

the edge was often a herring-bone or laurel-leaf

border, and occasionally the whole of the central

space within the hour ring was finely embellished

with engraving; more often the centre was matted,

and in some examples a sketch in the form of

birds and foliage bordered the aperture showing

the day of the month; this had a good effect

when burnished bright in contrast to the matting.

Further relief was given by turning a number of

rings around the winding holes. On the earliest

of the seventeenth - century clocks the maker's

name was as a rule inscribed in a straight line

along the bottom of the dial, usually in Latin, thus

—"Henricus Jones, Londini, fecit," visible only

189