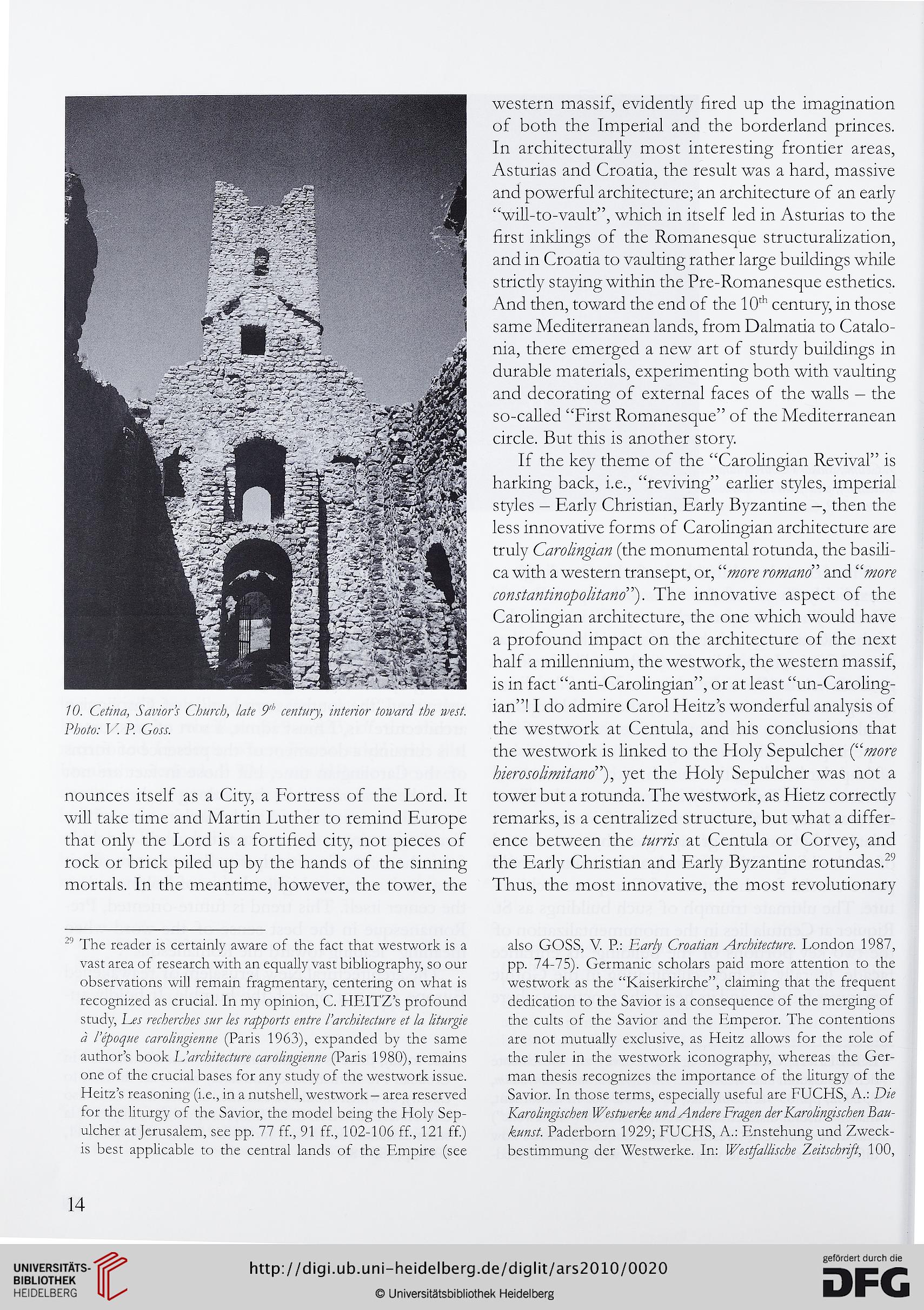

70. Chy'/M, MEcrl EL A ^^7/vry, 7%7í*Ect 7<?^A 7T?ř MvtV

P^oL.* IX P. Gč<v.

nounces itself as a City, a Fotttess of the Lord. It

will také time and Martin Luther to remind Europe

that only the Lord is a fortihed city, not pièces of

rock or brick piled up by the hands of the sinning

mortais. In the meantime, however, the tower, the

western massif, evidently hred up the imagination

of both the Imperiál and the borderland princes.

In architecturally most interesting frontier areas,

Asturias and Croatia, the result was a hard, massive

and powerful architecture; an architecture of an early

"will-to-vault", which in itself led in Asturias to the

hrst inklings of the Romanesque structuralization,

and in Croatia to vaulting rather large buildings while

strictly staying within the Pre-Romanesque esthetics.

And then, toward the end of the 1 (H Century, in those

same Mediterranean lands, from Dalmatia to Catalo-

nia, there emerged a new art of sturdy buildings in

durable materials, experimenting both with vaulting

and decorating of external faces of the walls — the

so-called "First Romanesque" of the Mediterranean

circle. But this is another story.

If the key theme of the "Carolingian Revival" is

harking back, i.e., "reviving" earlier styles, imperial

styles — Early Christian, Early Byzantine -, then the

less innovative forms of Carolingian architecture are

truly (the monumental rotunda, the basili-

ca with a western transept, or, "won? Twwwo" and "won?

oo^E^Ev<y?o//f^vo"). The innovative aspect of the

Carolingian architecture, the one which would hâve

a profound impact on the architecture of the next

half a millennium, the westwork, the western massif,

is in fact "anti-Carolingian", or at least "un-Caroling-

ian"! I do admire Carol Heitz's wonderfui analysis of

the westwork at Centula, and his conclusions that

the westwork is ltnked to the Holy Sepulcher ("won?

^Eroto^wE^o"), yet the Holy Sepulcher was not a

tower but a rotunda. The westwork, as Hietz correctly

remarks, is a centralized structure, but what a différ-

ence between the E/nA at Centula or Corvey, and

the Early Christian and Early Byzantine rotundasA

Thus, the most innovative, the most revolutionary

The reader is certainly aware of the fact that westwork is a

vast area of research with an equaliy vast bibliography, so our

observations will remain fragmentary, centering on what is

recognized as crucial. In my opinion, C. HEITZ's profound

study, Eřr jwr Lr E

4 (Paris 1963), expanded by the same

author's book EhrEiLfWr^ (Paris 1980), remains

one of the crucial bases for any study of the westwork issue.

Heitz's reasoning (i.e., in a nutshell, westwork — area reserved

for the liturgy of the Savior, the model being the Holy Sep-

ulcher atjerusalem, see pp. 77 ff., 91 ff., 102-106 ff., 121 ff.)

is best applicable to the central lands of the Empire (see

also GOSS, V. P: ELFy CroLE% ArtELrWn?. London 1987,

pp. 74-75). Germanie scholars paid more attention to the

westwork as the "Kaiserkirche", claiming that the frequent

dedication to the Savior is a conséquence of the merging of

the cuits of the Savior and the Emperor. The contentions

are not mutually exclusive, as Heitz allows for the role of

the ruler in the westwork iconography, whereas the Ger-

man thesis recognizes the importance of the liturgy of the

Savior. In those terms, especially useful are FUCHS, A.: DL

ITkVMwA Ar TGwEAvA/?

Paderborn 1929; FUCHS, A.: Enstehung und Zweck-

bestimmung der Westwerke. In: UTryLAsvA ZřAiAy/7, 100,

14