152

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

[October 20, 1860.

PUNCH’S BOOK OF BRITISH COSTUMES.

CHAPTER XXXIII.—IN WHICH WE BID GOOD BYE TO

HENRY IV. AND V., AND SAY HOWDEDO TO HENRY VI.

!P the elegant costumes

which were worn by the

civilians in the two first of

these reigns, we gave in our

last chapter an elegant de-

scription. It now remains

for us to say a word or two

about the armour and the

arms which were in use

about that period, although

in neither of them is there

much of novelty presented

to our notice. We observe

however that the steel shoe,

or solleret, was sometimes

laid aside, and that its place

was supplied by footed stir-

rups. Moreover there is

certainly a marked increase

of splendour in the mili-

tary equipment. The swell

knights of the day wore

around their bascinet a rich

wreath or band; and the

border of their jupon was

still elegantly cut into the

form of foliage, notwith-

standing the provisions of

the sumptuary statutes.

With regard to this quaint

fashion of cutting borders

into leaves, one of the old

writers (who never lost a

chance of playing upon

words) states that English

tailors “ first did take

French leave to take it from the French : ” but it is a^ matter of

some doubt to us, whether this remark was based ou actual truth, or

was merely made for the small pun which it involved. Somewhat

questionable likewise to our mind seems the story of how when King

Henry the Fourth was asked, if his jupon should be bordered with

an oakleaf or an ashleaf, he replied, “ 1 had as lief to leave it to the

knave to indent which leaf he liketh; for if he trieth to make an oak-

leaf he is full sure to make a (h)ash of it! ”

Since the time of Edward the Third civilians had not seldom worn

feathers in their caps; but, excepting as heraldic crests, plumes had

not been sported by knights until this period. In the reign of Henry

the Fieth we first find them adopted as military ornaments; and they

either were stuck upright on the helmet or the bascinet (in which

event the plume was called, correctly, a “panache”), or, at a later

time, were worn at the side, or falling backward, when the proper term

to apply to them was “plume.” We mention this distinction just to

show our readers how minutely accurate we can be if we choose; but

as these minute descriptions are generally dull, we cannot let them

often intrude upon our space.

The great crested helmet, called otherwise the heaume, was now

exclusively reserved for wearing at the tournament: as the bascinet

sufficed for ordinary purposes, shielding wearers from the blows of

weapons and of winds. This headpiece we described when it was

introduced (namely in the reigns of Edward the First and Second,

and of course our careful readers must remember our description. All

that we need add to it is, that at this period its shape was slightly

changed, being curved behind so as to be more closely fitting to the

head. In this respect it bore resemblance to the salade, a kind of

German headpiece introduced in the next reign. We must take care

not to mix this salade with the bascinet, because the two, although so

much alike, were really different; and as the salade was first used as

an article for dressing in the time of Henry the Sixth, it would be

premature to say at present much about it.

A fashion somewhat curious was that of wearing with the armour

large loose^ hanging sleeves, made of cloth or silk or even richer sub-

stances. These in general were part of a kind of cloak, or surcoat,

thrown over the whole suit; but sometimes they are shown as though

they were detached, and were worn without the surcoat, being fastened

to the shoulder, and falling to the wrist.

For further information respecting the knightly equipment of this

period the reader will do well to read up what is said about it by

Monstrelet, St. Hemy, Elmham, Bonnard, Froissart, Cotgrave,

Chaucer, Occleve, Shakspeare, Ashmore, Meyrick, Mills, Fos-

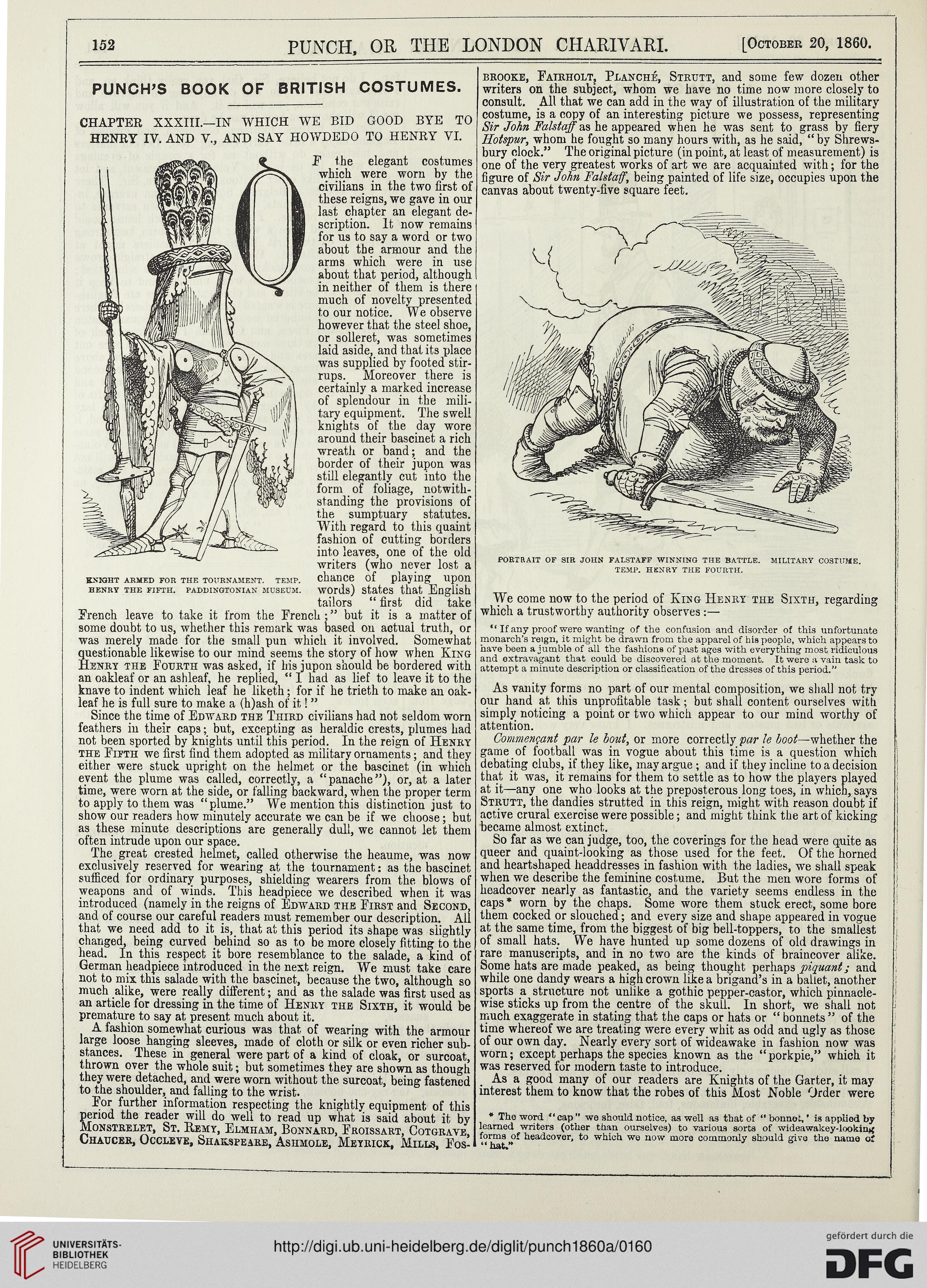

brooke, Fairholt, Planche, Strutt, and some few dozen other

writers on the subject, whom we have no time now more closely to

consult. All that we can add in the way of illustration of the military

costume, is a copy of an interesting picture we possess, representing

Sir John Falstaff as he appeared when he was sent to grass by fiery

Hotspur, whom he fought so many hours with, as he said, “by Shrews-

bury clock.” The original picture (in point, at least of measurement) is

one of the very greatest works of art we are acquainted with; for the

figure of Sir John Falstaff, being painted of life size, occupies upon the

canvas about twenty-five square feet.

PORTRAIT OF SIR JOHN FALSTAFF WINNING THE BATTLE. MILITARY COSTUME.

TEMP. HENRY THE FOURTH.

We come now to the period of King Henry the Sixth, regarding

which a trustworthy authority observes:—

“ If any proof were wanting of the confusion and disorder of this unfortunate

monarch’s reign, it might be drawn from the apparel of his people, which appears to

have been a jumble of all the fashions of past ages with everything most ridiculous

and extravagant that could be discovered at the moment. It were a vain task to

attempt a minute description or classification of the dresses of this period."

As vanity forms no part of our mental composition, we shall not try

our hand at this unprofitable task; but shall content ourselves with

simply noticing a point or two which appear to our mind worthy of

attention.

Commengant par le bout, or more correctly par le boot—whether the

game of football was in vogue about this time is a question which

debating clubs, if they like, may argue ; and if they incline to a decision

that it was, it remains for them to settle as to how the players played

at it—any one who looks at the preposterous long toes, in which, saj^s

Strutt, the dandies strutted in this reign, might with reason doubt if

active crural exercise were possible; and might think the art of kicking

became almost extinct.

So far as we can judge, too, the coverings for the head were quite as

queer and quaint-looking as those used for the feet. Of the horned I

and heartshaped headdresses in fashion with the ladies, we shall speak

when we describe the feminine costume. But the men wore forms of

headcover nearly as fantastic, and the variety seems endless in the

caps * worn by the chaps. Some wore them stuck erect, some bore

them cocked or slouched; and every size and shape appeared in vogue

at the same time, from the biggest of big bell-toppers, to the smallest

of small hats. We have hunted up some dozens of old drawings in

rare manuscripts, and in no two are the kinds of braincover alike.

Some hats are made peaked, as being thought perhaps piquant; and

while one dandy wears a hign crown like a brigand’s in a ballet, another

sports a structure not unlike a gothic pepper-castor, which pinnacle-

wise sticks up from the centre of the skuLl. In short, we shall not

much exaggerate in stating that the caps or hats or “ bonnets” of the

time whereof we are treating were every whit as odd and ugly as those

of our own day. Nearly every sort of wideawake in fashion now was

worn; except perhaps the species known as the “ porkpie,” which it

was reserved for modern taste to introduce.

As a good many of our readers are Knights of the Garter, it may

interest them to know that the robes of this Most Noble Order were

* The word “cap” we should notice, as well as that of “ bonnet, ’ is applied by

learned writers (other than ourselves) to various sorts of wideawakey-lookintf

forms of headcover, to which we now more commonly should give the name of

“ hat."

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

[October 20, 1860.

PUNCH’S BOOK OF BRITISH COSTUMES.

CHAPTER XXXIII.—IN WHICH WE BID GOOD BYE TO

HENRY IV. AND V., AND SAY HOWDEDO TO HENRY VI.

!P the elegant costumes

which were worn by the

civilians in the two first of

these reigns, we gave in our

last chapter an elegant de-

scription. It now remains

for us to say a word or two

about the armour and the

arms which were in use

about that period, although

in neither of them is there

much of novelty presented

to our notice. We observe

however that the steel shoe,

or solleret, was sometimes

laid aside, and that its place

was supplied by footed stir-

rups. Moreover there is

certainly a marked increase

of splendour in the mili-

tary equipment. The swell

knights of the day wore

around their bascinet a rich

wreath or band; and the

border of their jupon was

still elegantly cut into the

form of foliage, notwith-

standing the provisions of

the sumptuary statutes.

With regard to this quaint

fashion of cutting borders

into leaves, one of the old

writers (who never lost a

chance of playing upon

words) states that English

tailors “ first did take

French leave to take it from the French : ” but it is a^ matter of

some doubt to us, whether this remark was based ou actual truth, or

was merely made for the small pun which it involved. Somewhat

questionable likewise to our mind seems the story of how when King

Henry the Fourth was asked, if his jupon should be bordered with

an oakleaf or an ashleaf, he replied, “ 1 had as lief to leave it to the

knave to indent which leaf he liketh; for if he trieth to make an oak-

leaf he is full sure to make a (h)ash of it! ”

Since the time of Edward the Third civilians had not seldom worn

feathers in their caps; but, excepting as heraldic crests, plumes had

not been sported by knights until this period. In the reign of Henry

the Fieth we first find them adopted as military ornaments; and they

either were stuck upright on the helmet or the bascinet (in which

event the plume was called, correctly, a “panache”), or, at a later

time, were worn at the side, or falling backward, when the proper term

to apply to them was “plume.” We mention this distinction just to

show our readers how minutely accurate we can be if we choose; but

as these minute descriptions are generally dull, we cannot let them

often intrude upon our space.

The great crested helmet, called otherwise the heaume, was now

exclusively reserved for wearing at the tournament: as the bascinet

sufficed for ordinary purposes, shielding wearers from the blows of

weapons and of winds. This headpiece we described when it was

introduced (namely in the reigns of Edward the First and Second,

and of course our careful readers must remember our description. All

that we need add to it is, that at this period its shape was slightly

changed, being curved behind so as to be more closely fitting to the

head. In this respect it bore resemblance to the salade, a kind of

German headpiece introduced in the next reign. We must take care

not to mix this salade with the bascinet, because the two, although so

much alike, were really different; and as the salade was first used as

an article for dressing in the time of Henry the Sixth, it would be

premature to say at present much about it.

A fashion somewhat curious was that of wearing with the armour

large loose^ hanging sleeves, made of cloth or silk or even richer sub-

stances. These in general were part of a kind of cloak, or surcoat,

thrown over the whole suit; but sometimes they are shown as though

they were detached, and were worn without the surcoat, being fastened

to the shoulder, and falling to the wrist.

For further information respecting the knightly equipment of this

period the reader will do well to read up what is said about it by

Monstrelet, St. Hemy, Elmham, Bonnard, Froissart, Cotgrave,

Chaucer, Occleve, Shakspeare, Ashmore, Meyrick, Mills, Fos-

brooke, Fairholt, Planche, Strutt, and some few dozen other

writers on the subject, whom we have no time now more closely to

consult. All that we can add in the way of illustration of the military

costume, is a copy of an interesting picture we possess, representing

Sir John Falstaff as he appeared when he was sent to grass by fiery

Hotspur, whom he fought so many hours with, as he said, “by Shrews-

bury clock.” The original picture (in point, at least of measurement) is

one of the very greatest works of art we are acquainted with; for the

figure of Sir John Falstaff, being painted of life size, occupies upon the

canvas about twenty-five square feet.

PORTRAIT OF SIR JOHN FALSTAFF WINNING THE BATTLE. MILITARY COSTUME.

TEMP. HENRY THE FOURTH.

We come now to the period of King Henry the Sixth, regarding

which a trustworthy authority observes:—

“ If any proof were wanting of the confusion and disorder of this unfortunate

monarch’s reign, it might be drawn from the apparel of his people, which appears to

have been a jumble of all the fashions of past ages with everything most ridiculous

and extravagant that could be discovered at the moment. It were a vain task to

attempt a minute description or classification of the dresses of this period."

As vanity forms no part of our mental composition, we shall not try

our hand at this unprofitable task; but shall content ourselves with

simply noticing a point or two which appear to our mind worthy of

attention.

Commengant par le bout, or more correctly par le boot—whether the

game of football was in vogue about this time is a question which

debating clubs, if they like, may argue ; and if they incline to a decision

that it was, it remains for them to settle as to how the players played

at it—any one who looks at the preposterous long toes, in which, saj^s

Strutt, the dandies strutted in this reign, might with reason doubt if

active crural exercise were possible; and might think the art of kicking

became almost extinct.

So far as we can judge, too, the coverings for the head were quite as

queer and quaint-looking as those used for the feet. Of the horned I

and heartshaped headdresses in fashion with the ladies, we shall speak

when we describe the feminine costume. But the men wore forms of

headcover nearly as fantastic, and the variety seems endless in the

caps * worn by the chaps. Some wore them stuck erect, some bore

them cocked or slouched; and every size and shape appeared in vogue

at the same time, from the biggest of big bell-toppers, to the smallest

of small hats. We have hunted up some dozens of old drawings in

rare manuscripts, and in no two are the kinds of braincover alike.

Some hats are made peaked, as being thought perhaps piquant; and

while one dandy wears a hign crown like a brigand’s in a ballet, another

sports a structure not unlike a gothic pepper-castor, which pinnacle-

wise sticks up from the centre of the skuLl. In short, we shall not

much exaggerate in stating that the caps or hats or “ bonnets” of the

time whereof we are treating were every whit as odd and ugly as those

of our own day. Nearly every sort of wideawake in fashion now was

worn; except perhaps the species known as the “ porkpie,” which it

was reserved for modern taste to introduce.

As a good many of our readers are Knights of the Garter, it may

interest them to know that the robes of this Most Noble Order were

* The word “cap” we should notice, as well as that of “ bonnet, ’ is applied by

learned writers (other than ourselves) to various sorts of wideawakey-lookintf

forms of headcover, to which we now more commonly should give the name of

“ hat."