AROUND THE HISTORIOGRAP1IY OF

ITAL1AN GARDENS: GEORGINA MASSON'S CONTRIBUTION

33

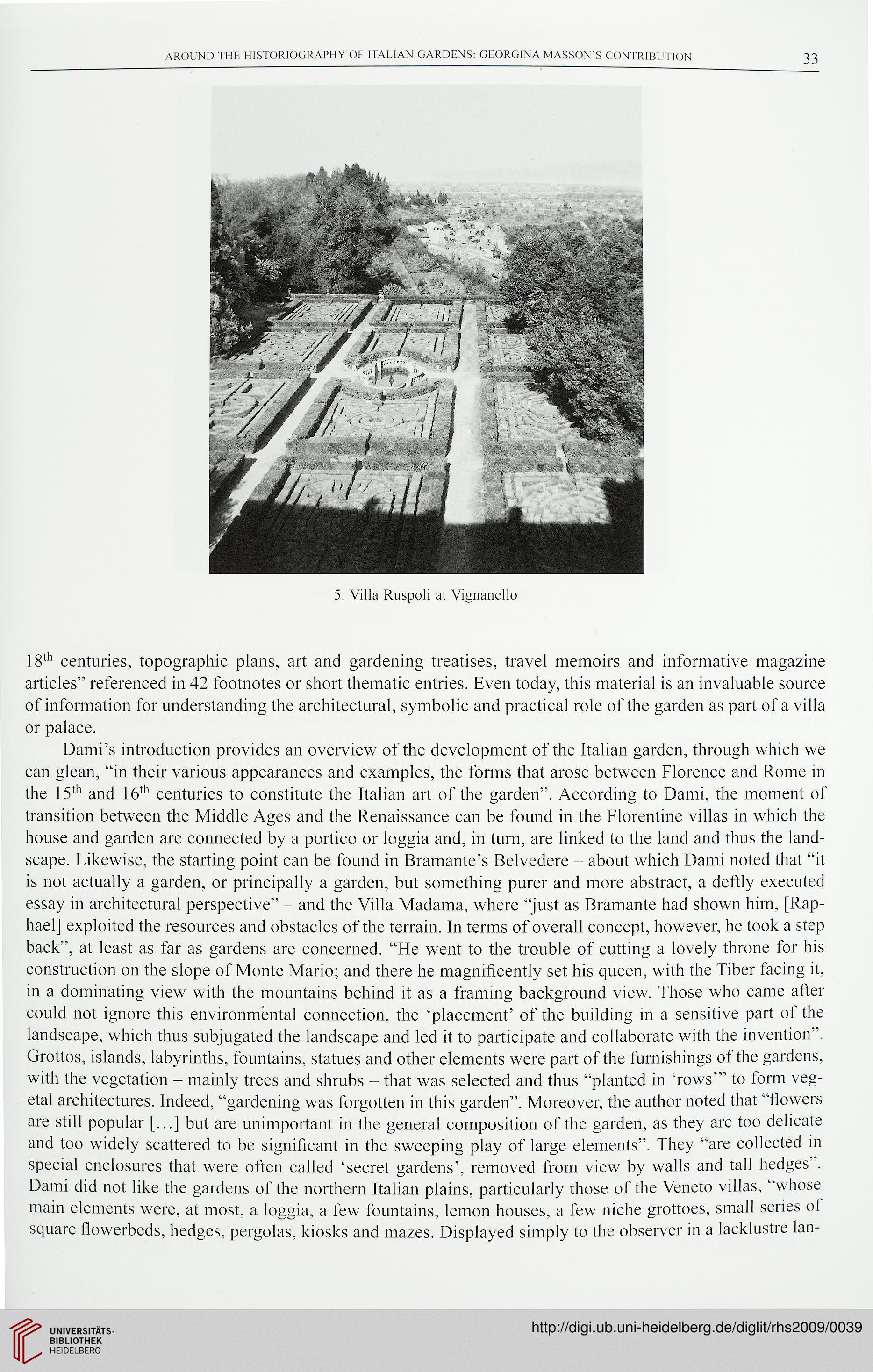

5. Villa Ruspoli at Vignanello

18lh centuries, topographie plans, art and gardening treatises, travel memoirs and informative magazine

articles" referenced in 42 footnotes or short thematic entries. Even today, this materiał is an invaluable source

of information for understanding the architectural, symbolic and practical role of the garden as part of a villa

or palace.

Dami's introduction provides an overview of the development of the Italian garden, through which we

can glean, "in their various appearances and examples, the forms that arose between Florence and Rome in

the 15th and 16th centuries to constitute the Italian art of the garden". According to Dami, the moment of

transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance can be found in the Florentine villas in which the

house and garden are connected by a portico or loggia and, in turn, are linked to the land and thus the land-

scape. Likewise, the starting point can be found in Bramante's Belvédère - about which Dami noted that "it

is not actually a garden, or principally a garden, but something purer and more abstract, a deftly executed

essay in architectural perspective" - and the Villa Madama, where "just as Bramante had shown him, [Rap-

haël] exploited the resources and obstacles of the terrain. In terms of overall concept, however, he took a step

back", at least as far as gardens are concerned. "He went to the trouble of cutting a lovely throne for his

construction on the slope of Monte Mario; and there he magnificently set his queen, with the Tiber facing it,

in a dominating view with the mountains behind it as a framing background view. Those who came after

could not ignore this environmëntal connection, the 'placement' of the building in a sensitive part of the

landscape, which thus subjugated the landscape and led it to participate and collaborate with the invention".

Grottos, islands, labyrinths, fountains, statues and other éléments were part of the furnishings of the gardens,

with the végétation - mainly trees and shrubs - that was selected and thus "planted in 'rows'" to form vég-

étal architectures. Indeed, "gardening was forgotten in this garden". Moreover, the author noted that "flowers

are still popular [...] but are unimportant in the gênerai composition of the garden, as they are too délicate

and too widely scattered to be significant in the sweeping play of large éléments". They "are collected in

spécial enclosures that were often called 'secret gardens', removed from view by walls and tall hedges".

Dami did not like the gardens of the northern Italian plains, particularly those of the Veneto villas, "whose

main éléments were, at most, a loggia, a few fountains, lemon houses, a few niche grottoes, small séries of

square flowerbeds, hedges, pergolas, kiosks and mazes. Displayed simply to the observer in a lacklustre lan-

ITAL1AN GARDENS: GEORGINA MASSON'S CONTRIBUTION

33

5. Villa Ruspoli at Vignanello

18lh centuries, topographie plans, art and gardening treatises, travel memoirs and informative magazine

articles" referenced in 42 footnotes or short thematic entries. Even today, this materiał is an invaluable source

of information for understanding the architectural, symbolic and practical role of the garden as part of a villa

or palace.

Dami's introduction provides an overview of the development of the Italian garden, through which we

can glean, "in their various appearances and examples, the forms that arose between Florence and Rome in

the 15th and 16th centuries to constitute the Italian art of the garden". According to Dami, the moment of

transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance can be found in the Florentine villas in which the

house and garden are connected by a portico or loggia and, in turn, are linked to the land and thus the land-

scape. Likewise, the starting point can be found in Bramante's Belvédère - about which Dami noted that "it

is not actually a garden, or principally a garden, but something purer and more abstract, a deftly executed

essay in architectural perspective" - and the Villa Madama, where "just as Bramante had shown him, [Rap-

haël] exploited the resources and obstacles of the terrain. In terms of overall concept, however, he took a step

back", at least as far as gardens are concerned. "He went to the trouble of cutting a lovely throne for his

construction on the slope of Monte Mario; and there he magnificently set his queen, with the Tiber facing it,

in a dominating view with the mountains behind it as a framing background view. Those who came after

could not ignore this environmëntal connection, the 'placement' of the building in a sensitive part of the

landscape, which thus subjugated the landscape and led it to participate and collaborate with the invention".

Grottos, islands, labyrinths, fountains, statues and other éléments were part of the furnishings of the gardens,

with the végétation - mainly trees and shrubs - that was selected and thus "planted in 'rows'" to form vég-

étal architectures. Indeed, "gardening was forgotten in this garden". Moreover, the author noted that "flowers

are still popular [...] but are unimportant in the gênerai composition of the garden, as they are too délicate

and too widely scattered to be significant in the sweeping play of large éléments". They "are collected in

spécial enclosures that were often called 'secret gardens', removed from view by walls and tall hedges".

Dami did not like the gardens of the northern Italian plains, particularly those of the Veneto villas, "whose

main éléments were, at most, a loggia, a few fountains, lemon houses, a few niche grottoes, small séries of

square flowerbeds, hedges, pergolas, kiosks and mazes. Displayed simply to the observer in a lacklustre lan-