Nicolas Gysis

lent as is their delicate colouring and their indefin-

able air of distinction, they give the impression

of having been seen before. Their subjects were

most of them founded on sketches made in Greece

and Asia Minor, where the artist was, of course,

thoroughly at home, and the)' combine the fresh-

ness of imagination of an unspoiled nature, with

the new mastery of technique and expression gained

in his earnest studies at Munich. Amongst the

earliest of these paintings of the first period must

be specially noted the Grandmother's Story, the

Painter in the Orient, the Carnival, and the Stealer

of Poultry, whilst amongst the later the Joseph ex-

plaining the Dreams and the Judith are perhaps the

most characteristic, and reveal yet another influence

—that of Hans Makart—for in them Gysis may

be said to have almost trodden on the heels of

the gifted young Austrian.

None of these subjects were, however, the true

metier of the Greek master, who was not really in

sympathy with genre—or, for that matter, with

history. He began, after producing the pictures

just enumerated, to develop his own particular

style—to be, in fact, himself. He now forgot

Piloty and his studio, and remembered only that

he was Gysis, a Greek, born beneath the sky

which had witnessed the production of the greatest

masterpieces ever conceived in a human brain.

The most salient characteristics of his genius are

idealism, depth of emotional feeling, and intensity

of intellectual vision. He saw everything in

nature with the undimmed eyes of the poet; he

painted what he saw with the skilled hand of an

expert. Nature aroused in him feelings full of a

profound mystery, and evoked in his imagination

figures instinct with nobility, ideally beautiful, and

of sculpturesque majesty, incarnations of the re-

fined classicism and romanticism which brought

him, as it were, into direct touch with the very

spirit, the inner essence of the antique Greek art

from which his own is derived by right of direct

inheritance. The study of the work of Gysis, in

fact, recalls a certain definition of neo-idealism :

"After naturalism has taught artists to work from

actual impressions of real scenes in an independent

manner, a transition was brought about by some

amongst them who embodied impressions made

upon their own minds, in an original manner which

they had not borrowed from the old masters."

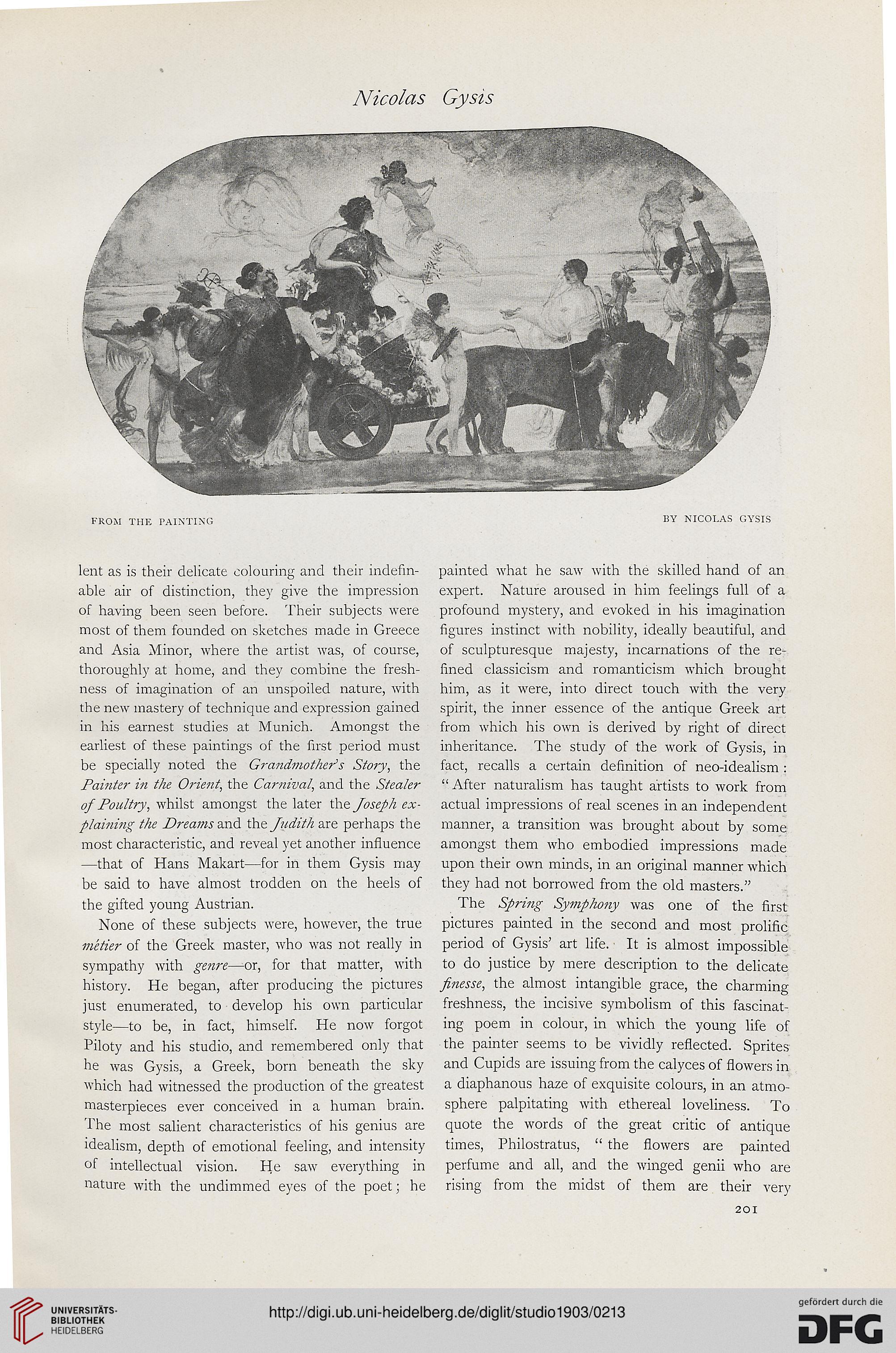

The Spring Symplwny was one of the first

pictures painted in the second and most prolific

period of Gysis' art life. It is almost impossible

to do justice by mere description to the delicate

finesse, the almost intangible grace, the charming

freshness, the incisive symbolism of this fascinat-

ing poem in colour, in which the young life of

the painter seems to be vividly reflected. Sprites

and Cupids are issuing from the calyces of flowers in

a diaphanous haze of exquisite colours, in an atmo-

sphere palpitating with ethereal loveliness. To

quote the words of the great critic of antique

times, Philostratus, " the flowers are painted

perfume and all, and the winged genii who are

rising from the midst of them are their very

20I

lent as is their delicate colouring and their indefin-

able air of distinction, they give the impression

of having been seen before. Their subjects were

most of them founded on sketches made in Greece

and Asia Minor, where the artist was, of course,

thoroughly at home, and the)' combine the fresh-

ness of imagination of an unspoiled nature, with

the new mastery of technique and expression gained

in his earnest studies at Munich. Amongst the

earliest of these paintings of the first period must

be specially noted the Grandmother's Story, the

Painter in the Orient, the Carnival, and the Stealer

of Poultry, whilst amongst the later the Joseph ex-

plaining the Dreams and the Judith are perhaps the

most characteristic, and reveal yet another influence

—that of Hans Makart—for in them Gysis may

be said to have almost trodden on the heels of

the gifted young Austrian.

None of these subjects were, however, the true

metier of the Greek master, who was not really in

sympathy with genre—or, for that matter, with

history. He began, after producing the pictures

just enumerated, to develop his own particular

style—to be, in fact, himself. He now forgot

Piloty and his studio, and remembered only that

he was Gysis, a Greek, born beneath the sky

which had witnessed the production of the greatest

masterpieces ever conceived in a human brain.

The most salient characteristics of his genius are

idealism, depth of emotional feeling, and intensity

of intellectual vision. He saw everything in

nature with the undimmed eyes of the poet; he

painted what he saw with the skilled hand of an

expert. Nature aroused in him feelings full of a

profound mystery, and evoked in his imagination

figures instinct with nobility, ideally beautiful, and

of sculpturesque majesty, incarnations of the re-

fined classicism and romanticism which brought

him, as it were, into direct touch with the very

spirit, the inner essence of the antique Greek art

from which his own is derived by right of direct

inheritance. The study of the work of Gysis, in

fact, recalls a certain definition of neo-idealism :

"After naturalism has taught artists to work from

actual impressions of real scenes in an independent

manner, a transition was brought about by some

amongst them who embodied impressions made

upon their own minds, in an original manner which

they had not borrowed from the old masters."

The Spring Symplwny was one of the first

pictures painted in the second and most prolific

period of Gysis' art life. It is almost impossible

to do justice by mere description to the delicate

finesse, the almost intangible grace, the charming

freshness, the incisive symbolism of this fascinat-

ing poem in colour, in which the young life of

the painter seems to be vividly reflected. Sprites

and Cupids are issuing from the calyces of flowers in

a diaphanous haze of exquisite colours, in an atmo-

sphere palpitating with ethereal loveliness. To

quote the words of the great critic of antique

times, Philostratus, " the flowers are painted

perfume and all, and the winged genii who are

rising from the midst of them are their very

20I