Alphonse Legros

in accordance with their ideals, and so become feel with him in his handling of subjects which are far

imaginatively their kinsman, their contemporary. remote from our everyday experience. His point

But this way of studying the past is so difficult that of view must become ours, and we must never for

it has only a few devotees. It requires from all a moment hold the conceited opinion that it is a

who would follow it such histrionic gifts of imagi- part of his business to please us at a first glance,

nation as must needs be very rare, so enslaved are To him all prettinesses of style, all kickshaws of

we ordinary men by the habits of mind peculiar to boudoir sentiment, are detestable—as detestable as

our own brief time. And this is partly why one has they were to Holbein, to Diirer, to Michael Angelo,

dwelt so long on the historic feeling expressed with to Titian, to Ingres, to J. F. Millet, and to all the

dramatised truth in the Death of St. Francis. other men of genius whom he loves best, and with

The same qualities are to be found elsewhere, in whom he dwells in the upper regions of art. Men

many of the best etchings produced by Mr. Legros; of this dominant and austere trend of thought are

and hence we must either be content to misunder- rarely to be found among artists of British birth;

stand the master's aims and results, or else we must indeed, to find a parallel to Legros among our

British countrymen of the

nineteenth century, we

must pass from the history

of art to that of letters, and

find in Carlyle the very

. man we need. They have

certainly much in common,

i these two, Carlyle and

Legros, not merely in a

| '^^^^^jm'>' >~ certain kinship of style,

\J but also in their habit

of dramatising everything,

> and of intensifying pity

and terror and pathos with

contrasts of humour some-

what grotesque in kind.

Both, again, speak to us

in many voices not their

own, yet the work of each

can never be called an

exercise in the ventrilo-

quism of art. Always in-

tensely individual, it is

known at once; no critic

could ever mistake it for

• 1 the work of anyone else.

Kb Last of all, Mr. Legros is

like Carlyle in his isolation

among his contemporaries

—an isolation caused by

stern convictions, which

to most people seem out

of date; but Mr. Legros

does not lose his temper

over it, as Carlyle did

frequently. Never once

has he departed from

" HHHHHHHH the austere dignity and

calm of his favourite

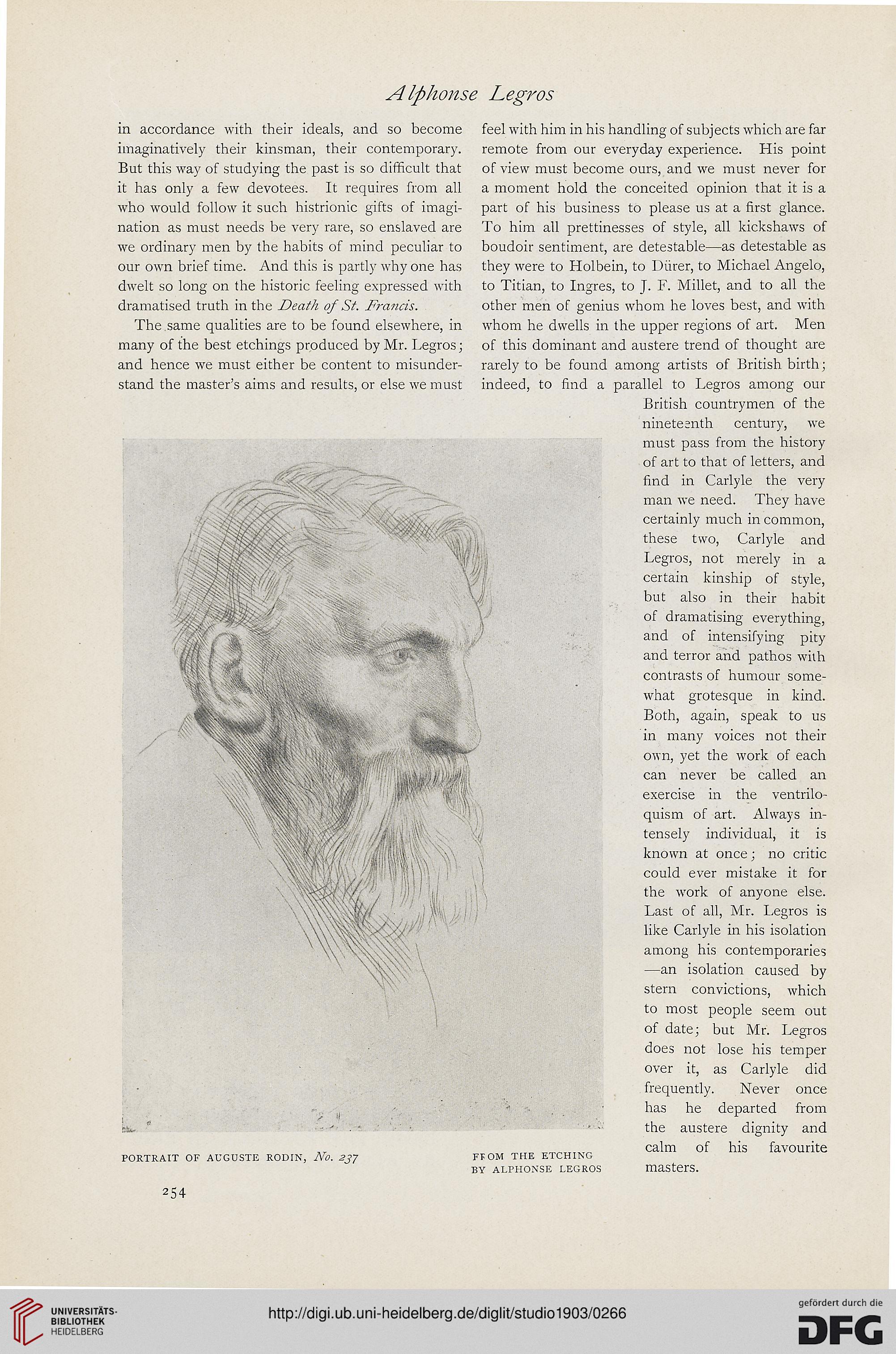

PORTRAIT OF AUGUSTE RODIN, No. 23J FtOM THE ElCHItsG

by alphonse legros masters.

2S4

in accordance with their ideals, and so become feel with him in his handling of subjects which are far

imaginatively their kinsman, their contemporary. remote from our everyday experience. His point

But this way of studying the past is so difficult that of view must become ours, and we must never for

it has only a few devotees. It requires from all a moment hold the conceited opinion that it is a

who would follow it such histrionic gifts of imagi- part of his business to please us at a first glance,

nation as must needs be very rare, so enslaved are To him all prettinesses of style, all kickshaws of

we ordinary men by the habits of mind peculiar to boudoir sentiment, are detestable—as detestable as

our own brief time. And this is partly why one has they were to Holbein, to Diirer, to Michael Angelo,

dwelt so long on the historic feeling expressed with to Titian, to Ingres, to J. F. Millet, and to all the

dramatised truth in the Death of St. Francis. other men of genius whom he loves best, and with

The same qualities are to be found elsewhere, in whom he dwells in the upper regions of art. Men

many of the best etchings produced by Mr. Legros; of this dominant and austere trend of thought are

and hence we must either be content to misunder- rarely to be found among artists of British birth;

stand the master's aims and results, or else we must indeed, to find a parallel to Legros among our

British countrymen of the

nineteenth century, we

must pass from the history

of art to that of letters, and

find in Carlyle the very

. man we need. They have

certainly much in common,

i these two, Carlyle and

Legros, not merely in a

| '^^^^^jm'>' >~ certain kinship of style,

\J but also in their habit

of dramatising everything,

> and of intensifying pity

and terror and pathos with

contrasts of humour some-

what grotesque in kind.

Both, again, speak to us

in many voices not their

own, yet the work of each

can never be called an

exercise in the ventrilo-

quism of art. Always in-

tensely individual, it is

known at once; no critic

could ever mistake it for

• 1 the work of anyone else.

Kb Last of all, Mr. Legros is

like Carlyle in his isolation

among his contemporaries

—an isolation caused by

stern convictions, which

to most people seem out

of date; but Mr. Legros

does not lose his temper

over it, as Carlyle did

frequently. Never once

has he departed from

" HHHHHHHH the austere dignity and

calm of his favourite

PORTRAIT OF AUGUSTE RODIN, No. 23J FtOM THE ElCHItsG

by alphonse legros masters.

2S4