The Water-Colours of Alfred W. Rich

’

&

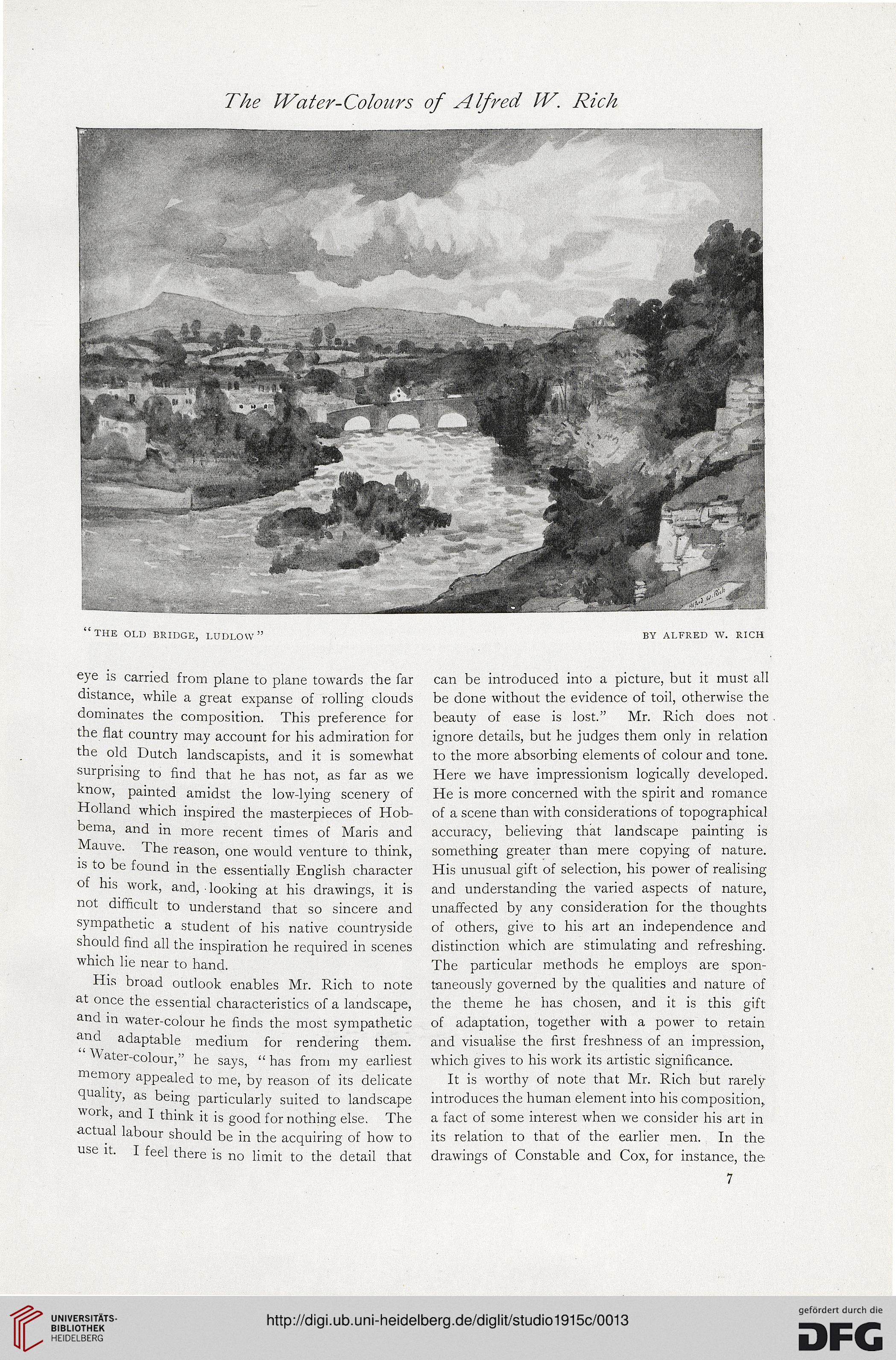

“THE OLD BRIDGE, LUDLOW”

BY ALFRED W. RICH

eye is carried from plane to plane towards the far

distance, while a great expanse of rolling clouds

dominates the composition. This preference for

the flat country may account for his admiration for

the old Dutch landscapists, and it is somewhat

surprising to find that he has not, as far as we

know, painted amidst the low-lying scenery of

Holland which inspired the masterpieces of Hob-

bema, and in more recent times of Maris and

Mauve. The reason, one would venture to think,

is to be found in the essentially English character

of his work, and, looking at his drawings, it is

not difficult to understand that so sincere and

sympathetic a student of his native countryside

should find all the inspiration he required in scenes

which lie near to hand.

His broad outlook enables Mr. Rich to note

at once the essential characteristics of a landscape,

and in water-colour he finds the most sympathetic

and adaptable medium for rendering them.

" ater-colour,” he says, “ has from my earliest

memory appealed to me, by reason of its delicate

quality, as being particularly suited to landscape

"°rk, and I think it is good for nothing else. The

actual labour should be in the acquiring of how to

use it. I feel there is no limit to the detail that

can be introduced into a picture, but it must all

be done without the evidence of toil, otherwise the

beauty of ease is lost.” Mr. Rich does not

ignore details, but he judges them only in relation

to the more absorbing elements of colour and tone.

Here we have impressionism logically developed.

He is more concerned with the spirit and romance

of a scene than with considerations of topographical

accuracy, believing that landscape painting is

something greater than mere copying of nature.

His unusual gift of selection, his power of realising

and understanding the varied aspects of nature,

unaffected by any consideration for the thoughts

of others, give to his art an independence and

distinction which are stimulating and refreshing.

The particular methods he employs are spon-

taneously governed by the qualities and nature of

the theme he has chosen, and it is this gift

of adaptation, together with a power to retain

and visualise the first freshness of an impression,

which gives to his work its artistic significance.

It is worthy of note that Mr. Rich but rarely

introduces the human element into his composition,

a fact of some interest when we consider his art in

its relation to that of the earlier men. In the

drawings of Constable and Cox, for instance, the

7

’

&

“THE OLD BRIDGE, LUDLOW”

BY ALFRED W. RICH

eye is carried from plane to plane towards the far

distance, while a great expanse of rolling clouds

dominates the composition. This preference for

the flat country may account for his admiration for

the old Dutch landscapists, and it is somewhat

surprising to find that he has not, as far as we

know, painted amidst the low-lying scenery of

Holland which inspired the masterpieces of Hob-

bema, and in more recent times of Maris and

Mauve. The reason, one would venture to think,

is to be found in the essentially English character

of his work, and, looking at his drawings, it is

not difficult to understand that so sincere and

sympathetic a student of his native countryside

should find all the inspiration he required in scenes

which lie near to hand.

His broad outlook enables Mr. Rich to note

at once the essential characteristics of a landscape,

and in water-colour he finds the most sympathetic

and adaptable medium for rendering them.

" ater-colour,” he says, “ has from my earliest

memory appealed to me, by reason of its delicate

quality, as being particularly suited to landscape

"°rk, and I think it is good for nothing else. The

actual labour should be in the acquiring of how to

use it. I feel there is no limit to the detail that

can be introduced into a picture, but it must all

be done without the evidence of toil, otherwise the

beauty of ease is lost.” Mr. Rich does not

ignore details, but he judges them only in relation

to the more absorbing elements of colour and tone.

Here we have impressionism logically developed.

He is more concerned with the spirit and romance

of a scene than with considerations of topographical

accuracy, believing that landscape painting is

something greater than mere copying of nature.

His unusual gift of selection, his power of realising

and understanding the varied aspects of nature,

unaffected by any consideration for the thoughts

of others, give to his art an independence and

distinction which are stimulating and refreshing.

The particular methods he employs are spon-

taneously governed by the qualities and nature of

the theme he has chosen, and it is this gift

of adaptation, together with a power to retain

and visualise the first freshness of an impression,

which gives to his work its artistic significance.

It is worthy of note that Mr. Rich but rarely

introduces the human element into his composition,

a fact of some interest when we consider his art in

its relation to that of the earlier men. In the

drawings of Constable and Cox, for instance, the

7