Mr. Clausens Work in Water-Colour

The Society of Twelve, always sound a distinct

note in any assemblage of pictures; to vary the

metaphor, they seem to open a window through

which streams in a revivifying breeze, clear sun-

light, and the fresh smell of the earth.

Even in a black-and-white reproduction—and

it must be borne in mind that these water-colours

depend for effect almost entirely upon their colour

-—one catches something of that sense of atmo-

sphere and light which the artist captures so simply

and directly, yet withal so dexterously and with

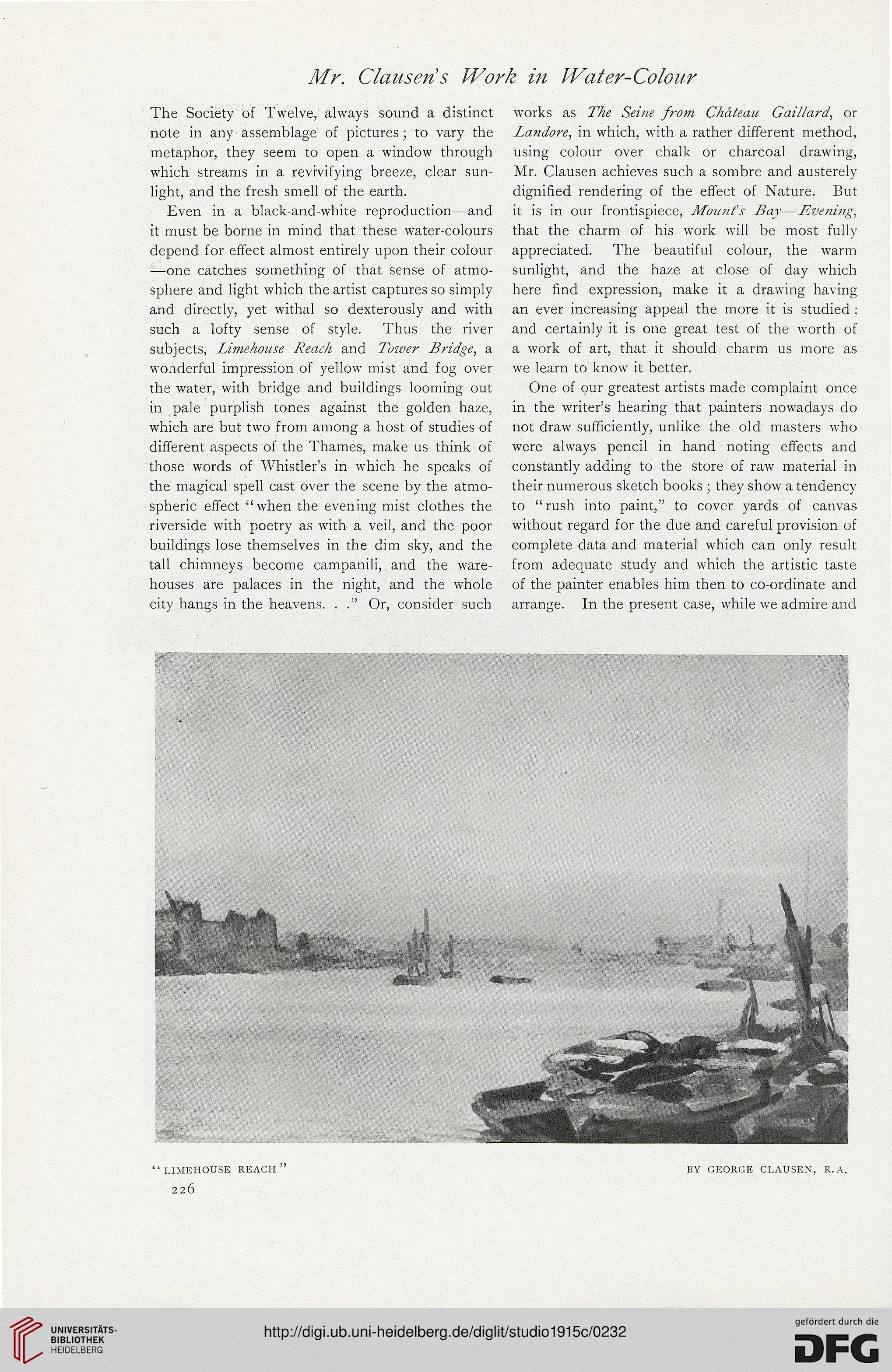

such a lofty sense of style. Thus the river

subjects, Limehouse Reach and Tower Bridge, a

wonderful impression of yellow mist and fog over

the water, with bridge and buildings looming out

in pale purplish tones against the golden haze,

which are but two from among a host of studies of

different aspects of the Thames, make us think of

those words of Whistler’s in which he speaks of

the magical spell cast over the scene by the atmo-

spheric effect “when the evening mist clothes the

riverside with poetry as with a veil, and the poor

buildings lose themselves in the dim sky, and the

tall chimneys become campanili, and the ware-

houses are palaces in the night, and the whole

city hangs in the heavens. . .” Or, consider such

works as The Seine from Chhteau Gaillard, or

Landore, in which, with a rather different method,

using colour over chalk or charcoal drawing,

Mr. Clausen achieves such a sombre and austerely

dignified rendering of the effect of Nature. But

it is in our frontispiece, Mount's Bay—Evening,

that the charm of his work will be most fully

appreciated. The beautiful colour, the warm

sunlight, and the haze at close of day which

here find expression, make it a drawing having

an ever increasing appeal the more it is studied ;

and certainly it is one great test of the worth of

a work of art, that it should charm us more as

we learn to know it better.

One of our greatest artists made complaint once

in the writer’s hearing that painters nowadays do

not draw sufficiently, unlike the old masters who

were always pencil in hand noting effects and

constantly adding to the store of raw material in

their numerous sketch books ; they show a tendency

to “ rush into paint,” to cover yards of canvas

without regard for the due and careful provision of

complete data and material which can only result

from adequate study and which the artistic taste

of the painter enables him then to co-ordinate and

arrange. In the present case, while we admire and

The Society of Twelve, always sound a distinct

note in any assemblage of pictures; to vary the

metaphor, they seem to open a window through

which streams in a revivifying breeze, clear sun-

light, and the fresh smell of the earth.

Even in a black-and-white reproduction—and

it must be borne in mind that these water-colours

depend for effect almost entirely upon their colour

-—one catches something of that sense of atmo-

sphere and light which the artist captures so simply

and directly, yet withal so dexterously and with

such a lofty sense of style. Thus the river

subjects, Limehouse Reach and Tower Bridge, a

wonderful impression of yellow mist and fog over

the water, with bridge and buildings looming out

in pale purplish tones against the golden haze,

which are but two from among a host of studies of

different aspects of the Thames, make us think of

those words of Whistler’s in which he speaks of

the magical spell cast over the scene by the atmo-

spheric effect “when the evening mist clothes the

riverside with poetry as with a veil, and the poor

buildings lose themselves in the dim sky, and the

tall chimneys become campanili, and the ware-

houses are palaces in the night, and the whole

city hangs in the heavens. . .” Or, consider such

works as The Seine from Chhteau Gaillard, or

Landore, in which, with a rather different method,

using colour over chalk or charcoal drawing,

Mr. Clausen achieves such a sombre and austerely

dignified rendering of the effect of Nature. But

it is in our frontispiece, Mount's Bay—Evening,

that the charm of his work will be most fully

appreciated. The beautiful colour, the warm

sunlight, and the haze at close of day which

here find expression, make it a drawing having

an ever increasing appeal the more it is studied ;

and certainly it is one great test of the worth of

a work of art, that it should charm us more as

we learn to know it better.

One of our greatest artists made complaint once

in the writer’s hearing that painters nowadays do

not draw sufficiently, unlike the old masters who

were always pencil in hand noting effects and

constantly adding to the store of raw material in

their numerous sketch books ; they show a tendency

to “ rush into paint,” to cover yards of canvas

without regard for the due and careful provision of

complete data and material which can only result

from adequate study and which the artistic taste

of the painter enables him then to co-ordinate and

arrange. In the present case, while we admire and