212

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

[December 1, I860.

modern pegtops, and allotted them Bath post at sixpence a quire.

May we not learn something from that Prse-Raphaelite, that prae-riff-

raffaelite a?e ? They were fine fellows after all, those Early English

Heroes. Take Richard Cceor de Lion—I am influenced by no

private prejudice, but I ask any one—I ask Tom Sayers what his

opinion is of a man who could cut a sheep through at a single blow,

and made no more of cleaving a bar of iron in twain than my grand-

mother would of breaking a knitting needle ? There’s a man for you !

and haven’t we Mr. Oliver Goldsmith’s direct testimony that

Richard generously forgave the wretch who caused his death at

Chalus? There’S a hero for you, and where is his monument I should

like to know P

“ Just as I reach this point in my soliloquy, a sharp shrill sound

uncommonly like a railway whistle, strikes on my ear. What can

it be ? There it is again, louder and nearer, accompanied by the short

energetic puffs of a locomotive. 1 look inquiringly at my friends the

vergers who glance interrogatively at each other, and then we all run

out of Poet’s Corner together, and look down towards Parliament

Street, where a crowd of people have assembled. Lo! whose is this

giant form which stands out dark against, the London sky and makes

the Hansom cabs seem very pigmies ? Who is this mail-clad warrior

with haughty mien and outstretched arm, riding like a god above the

crowd ? Volumes of steam surround his charger’s head, and we seem

to hear the noble beast snorting as he prances by. We all stand still

and wonder. Street boys throw up their caps and cheer. Even the

cabmen for a brief moment forget their fares and pull up to have a look.

Can 1 be mistaken p Those handsome bronzed features—that steed of

mettle yielding to an iron sway. No! It is Richard of the Lion

Heart riding triumphant into Palace Yard.

* * * * * * ' *

“ By this time yon will doubtless perceive that I have been de-

scribing in my romantic style, the arrival of Marochetti’s equestrian

statue of the great Crusader which has just been set up at Westminster.

The wondrous snorts and steam emanated I admit not from the

warrior’s horse but from one of Bray’s traction engines which dragged

the statue to the spot. Now was not this a sight to see! The twelfth

and nineteenth centuries thus linked together. To see Cceur de

Lion preceded by a locomotive! Bravo, Marochetti ! Bravo,

James Watt ! Science and Art go hand in hand. Slowly and majes-

tically they approach. A great scaffold has been prepared for hoisting

the Warrior King, and presently a stout mechanic leaps upon his

shoulder. Another is astride the horse’s head, and a dozen more are

at work below. For a few minutes the Liou heart has to submit to a

little indignity, and is bound with ropes and chains; at last the mass

begins to move; rises gently; swings in mid air; all! if I had designed

that noble aroup what would have been my feelings at that moment?

an unsteady hand, an unseen flaw—one slight defect in that ingenious

machinery, might have sent the whole seven tons of metal thundering

to the eart h, and the labour of years would have been lost. Dii avertite

casum! We hold our breaths while Richard sways to and fro. A

little pull that way towards the pedestal, and the danger is past.

“Unwind the ignoble hemp—strike off his chains—Richard’s

himself again. Yours faithfully,

“ Jack Easel.”

PUNCH’S BOOK OF BRITISH COSTUMES.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.—A SECOND SIGHT (WITHOUT CLAIR-

VOYANCE) AT THE LADIES OF THE 15th CENTURY.

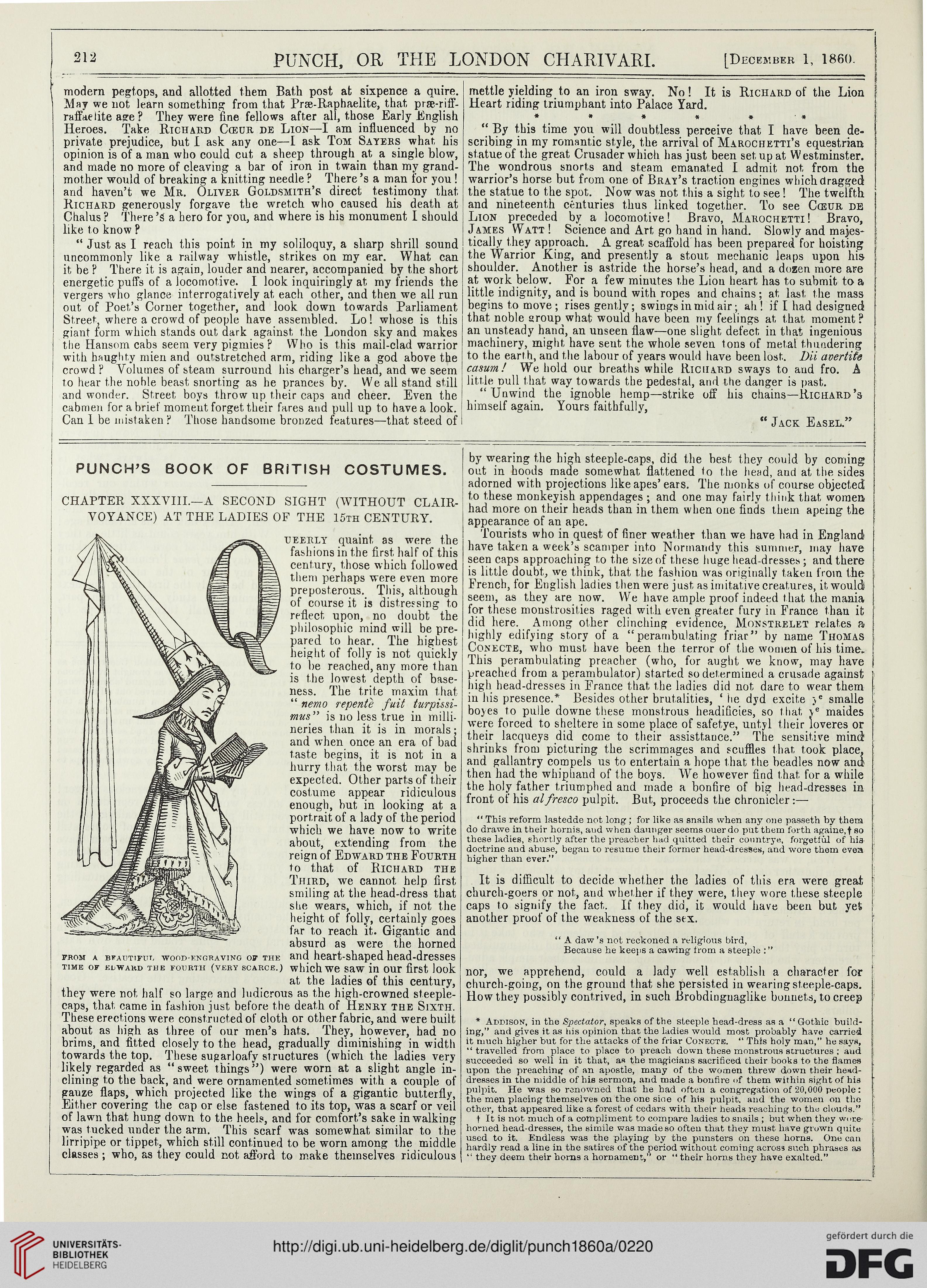

ueerly quaint as were the

fashions in the first half of this

century, those which followed

them perhaps were even more

preposterous. This, although

of course it is distressing to

reflect upon, no doubt the

philosophic mind will be pre-

pared to hear. The highest

height of folly is not quickly

to be reached, any more than

is the lowest depth of base-

ness. The trite maxim that

“ nemo repent e fuit turpissi-

mus” is no less true in milli-

neries than it is in morals;

and when once an era of bad

taste begins, it is not in a

hurry that the worst may be

expected. Other parts of their

costume appear ridiculous

enough, but in looking at a

portrait of a lady of the period

which we have now to write

about, extending from the

reign of Edward the Fourth

to that of Richard the

Third, we cannot help first

smiling at the head-dress that

she wears, which, if not the

height of folly, certainly goes

far to reach it. Gigantic and

absurd as were the horned

and heart-shaped head-dresses

which we saw in our first look

at the ladies of this century,

they were not half so large and ludicrous as the high-crowned steeple-

caps, that came in fashion just before the death of Henry the Sixth.

These erections were constructed of cloth or other fabric, and were built

about as high as three of our men’s hats. They, however, had no

brims, and fitted closely to the head, gradually diminishing in width

towards the top. These sugarloafy structures (which the ladies very

likely regarded as “sweet things”) were worn at a slight angle in-

clining to the back, and were ornamented sometimes with a couple of

gauze flaps, which projected like the wings of a gigantic butterfly,

Either covering the cap or else fastened to its top, was a scarf or veil

of lawn that hung down to the heels, and for comfort’s sake in walking

was tucked under the arm. This scarf was somewhat similar to the

lirripipe or tippet, which still continued to be worn among the middle

classes ; who, as they could not afford to make themselves ridiculous

PROM A BFADTlFUr, WOOD-ENGRAVING OB' THE

TIME OF EDWARD THE FOURTH (VERY SCARCE.)

by wearing the high steeple-caps, did the best they could by coming

out in hoods made somewhat flattened to the head, aud at the sides

adorned with projections like apes’ ears. The monks of course objected

to these monkeyish appendages ; and one may fairly think that women

had more on their heads than in them when one finds them apeing the

appearance of an ape.

Tourists who in quest of finer weather than we have had in England

have taken a week’s scamper into Normandy this summer, may have

seen caps approaching to the size of these huge head-dresses ; and there

is little doubt, we think, that the fashiou was originally taken from the

French, for English ladies then were just as imitative creatures, it would

seem, as they are now. We have ample proof indeed that the mania

for these monstrosities raged with even greater fury in France than it

did here. Among other clinching evidence, Monstrelet relates a

highly edifying story of a “perambulating friar” by name Thomas

Conecte, who must have been the terror of the women of his time.

This perambulating preacher (who, for aught we know, may have

preached from a perambulator) started so determined a crusade against

high head-dresses in France that the ladies did not dare to wear them

in his presence.* Besides other brutalities, ‘ lie dyd excite ye smalle

boyes to pulle downe these monstrous headiflcies, so that \e maides 1

were forced to sheltere in some place of safetye, untyl their loveres or

their lacqueys did come to their assisttauce.” The sensitive mind

shrinks from picturing the scrimmages and scuffles that, took place,

and gallantry compels us to entertain a hope that the beadles now and

then had the whiphand of the boys. We however find that for a while

the holy father triumphed and made a bonfire of big head-dresses in

front of his alfresco pulpit. But, proceeds the chronicler:—

“ This reform lastedde not long; for like as snails when any one passeth by them

do drawe in their hornis, aud when daunger seems ouerdo put them forth againe.f so

these ladies, shortly after the preacher had quitted their conntrye, forgetful of his

doctrine aud abuse, begau to resume their former head-dresses, and wore them evea

higher than ever.”

It is difficult to decide whether the ladies of this era were great

church-goers or not, and whether if they were, they wore these steeple

caps lo signify the fact. If they did, it would have been but yet

another proof of the weakness of the sex.

“ A daw’s not reckoned a religious bird,

Because he keeps a cawing Irom a steeple

nor, we apprehend, could a lady well establish a character for

church-going, on the ground that she persisted in wearing st eeple-caps.

How they possibly contrived, in such Brobdinguaglike bonnets, to creep

* Addison, in the Spectator, speaks of the steeple head-dress as a “ Gothic build-

ing,” aud gives it as his opinion that the ladies would most probably have carried

it much higher but for the attacks of the friar Conecte. “ This holy man,” he says,

“ travelled from place to place to preach down these monstrous structures ; and

succeeded so well in it that, as the magicians sacrificed their books to the flames

upon the preaching of an apostle, many of tbe women threw down their head-

dresses in the middle of his sermon, and made a bonfire of them within sight of his

pulpit. He was so renowned that he had often a congregation of 20,000 people:

the men placing themselves on the one sioe of his pulpit, and the women ou the

other, that appeared like a forest of cedars with their heads reaching to the clouris.”

t It is not much of a compliment to compare ladies to snails ; but when they wore-

horned head-dresses, the simile was made so often that they must have grown quite

used to it. Endless was the playing by the punsters on these horns. One can

hardly read a line in the satires of the period without coming across such phrases as

“ they deem their horns a hornament,” or “ their horns they have exalted.”

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

[December 1, I860.

modern pegtops, and allotted them Bath post at sixpence a quire.

May we not learn something from that Prse-Raphaelite, that prae-riff-

raffaelite a?e ? They were fine fellows after all, those Early English

Heroes. Take Richard Cceor de Lion—I am influenced by no

private prejudice, but I ask any one—I ask Tom Sayers what his

opinion is of a man who could cut a sheep through at a single blow,

and made no more of cleaving a bar of iron in twain than my grand-

mother would of breaking a knitting needle ? There’s a man for you !

and haven’t we Mr. Oliver Goldsmith’s direct testimony that

Richard generously forgave the wretch who caused his death at

Chalus? There’S a hero for you, and where is his monument I should

like to know P

“ Just as I reach this point in my soliloquy, a sharp shrill sound

uncommonly like a railway whistle, strikes on my ear. What can

it be ? There it is again, louder and nearer, accompanied by the short

energetic puffs of a locomotive. 1 look inquiringly at my friends the

vergers who glance interrogatively at each other, and then we all run

out of Poet’s Corner together, and look down towards Parliament

Street, where a crowd of people have assembled. Lo! whose is this

giant form which stands out dark against, the London sky and makes

the Hansom cabs seem very pigmies ? Who is this mail-clad warrior

with haughty mien and outstretched arm, riding like a god above the

crowd ? Volumes of steam surround his charger’s head, and we seem

to hear the noble beast snorting as he prances by. We all stand still

and wonder. Street boys throw up their caps and cheer. Even the

cabmen for a brief moment forget their fares and pull up to have a look.

Can 1 be mistaken p Those handsome bronzed features—that steed of

mettle yielding to an iron sway. No! It is Richard of the Lion

Heart riding triumphant into Palace Yard.

* * * * * * ' *

“ By this time yon will doubtless perceive that I have been de-

scribing in my romantic style, the arrival of Marochetti’s equestrian

statue of the great Crusader which has just been set up at Westminster.

The wondrous snorts and steam emanated I admit not from the

warrior’s horse but from one of Bray’s traction engines which dragged

the statue to the spot. Now was not this a sight to see! The twelfth

and nineteenth centuries thus linked together. To see Cceur de

Lion preceded by a locomotive! Bravo, Marochetti ! Bravo,

James Watt ! Science and Art go hand in hand. Slowly and majes-

tically they approach. A great scaffold has been prepared for hoisting

the Warrior King, and presently a stout mechanic leaps upon his

shoulder. Another is astride the horse’s head, and a dozen more are

at work below. For a few minutes the Liou heart has to submit to a

little indignity, and is bound with ropes and chains; at last the mass

begins to move; rises gently; swings in mid air; all! if I had designed

that noble aroup what would have been my feelings at that moment?

an unsteady hand, an unseen flaw—one slight defect in that ingenious

machinery, might have sent the whole seven tons of metal thundering

to the eart h, and the labour of years would have been lost. Dii avertite

casum! We hold our breaths while Richard sways to and fro. A

little pull that way towards the pedestal, and the danger is past.

“Unwind the ignoble hemp—strike off his chains—Richard’s

himself again. Yours faithfully,

“ Jack Easel.”

PUNCH’S BOOK OF BRITISH COSTUMES.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.—A SECOND SIGHT (WITHOUT CLAIR-

VOYANCE) AT THE LADIES OF THE 15th CENTURY.

ueerly quaint as were the

fashions in the first half of this

century, those which followed

them perhaps were even more

preposterous. This, although

of course it is distressing to

reflect upon, no doubt the

philosophic mind will be pre-

pared to hear. The highest

height of folly is not quickly

to be reached, any more than

is the lowest depth of base-

ness. The trite maxim that

“ nemo repent e fuit turpissi-

mus” is no less true in milli-

neries than it is in morals;

and when once an era of bad

taste begins, it is not in a

hurry that the worst may be

expected. Other parts of their

costume appear ridiculous

enough, but in looking at a

portrait of a lady of the period

which we have now to write

about, extending from the

reign of Edward the Fourth

to that of Richard the

Third, we cannot help first

smiling at the head-dress that

she wears, which, if not the

height of folly, certainly goes

far to reach it. Gigantic and

absurd as were the horned

and heart-shaped head-dresses

which we saw in our first look

at the ladies of this century,

they were not half so large and ludicrous as the high-crowned steeple-

caps, that came in fashion just before the death of Henry the Sixth.

These erections were constructed of cloth or other fabric, and were built

about as high as three of our men’s hats. They, however, had no

brims, and fitted closely to the head, gradually diminishing in width

towards the top. These sugarloafy structures (which the ladies very

likely regarded as “sweet things”) were worn at a slight angle in-

clining to the back, and were ornamented sometimes with a couple of

gauze flaps, which projected like the wings of a gigantic butterfly,

Either covering the cap or else fastened to its top, was a scarf or veil

of lawn that hung down to the heels, and for comfort’s sake in walking

was tucked under the arm. This scarf was somewhat similar to the

lirripipe or tippet, which still continued to be worn among the middle

classes ; who, as they could not afford to make themselves ridiculous

PROM A BFADTlFUr, WOOD-ENGRAVING OB' THE

TIME OF EDWARD THE FOURTH (VERY SCARCE.)

by wearing the high steeple-caps, did the best they could by coming

out in hoods made somewhat flattened to the head, aud at the sides

adorned with projections like apes’ ears. The monks of course objected

to these monkeyish appendages ; and one may fairly think that women

had more on their heads than in them when one finds them apeing the

appearance of an ape.

Tourists who in quest of finer weather than we have had in England

have taken a week’s scamper into Normandy this summer, may have

seen caps approaching to the size of these huge head-dresses ; and there

is little doubt, we think, that the fashiou was originally taken from the

French, for English ladies then were just as imitative creatures, it would

seem, as they are now. We have ample proof indeed that the mania

for these monstrosities raged with even greater fury in France than it

did here. Among other clinching evidence, Monstrelet relates a

highly edifying story of a “perambulating friar” by name Thomas

Conecte, who must have been the terror of the women of his time.

This perambulating preacher (who, for aught we know, may have

preached from a perambulator) started so determined a crusade against

high head-dresses in France that the ladies did not dare to wear them

in his presence.* Besides other brutalities, ‘ lie dyd excite ye smalle

boyes to pulle downe these monstrous headiflcies, so that \e maides 1

were forced to sheltere in some place of safetye, untyl their loveres or

their lacqueys did come to their assisttauce.” The sensitive mind

shrinks from picturing the scrimmages and scuffles that, took place,

and gallantry compels us to entertain a hope that the beadles now and

then had the whiphand of the boys. We however find that for a while

the holy father triumphed and made a bonfire of big head-dresses in

front of his alfresco pulpit. But, proceeds the chronicler:—

“ This reform lastedde not long; for like as snails when any one passeth by them

do drawe in their hornis, aud when daunger seems ouerdo put them forth againe.f so

these ladies, shortly after the preacher had quitted their conntrye, forgetful of his

doctrine aud abuse, begau to resume their former head-dresses, and wore them evea

higher than ever.”

It is difficult to decide whether the ladies of this era were great

church-goers or not, and whether if they were, they wore these steeple

caps lo signify the fact. If they did, it would have been but yet

another proof of the weakness of the sex.

“ A daw’s not reckoned a religious bird,

Because he keeps a cawing Irom a steeple

nor, we apprehend, could a lady well establish a character for

church-going, on the ground that she persisted in wearing st eeple-caps.

How they possibly contrived, in such Brobdinguaglike bonnets, to creep

* Addison, in the Spectator, speaks of the steeple head-dress as a “ Gothic build-

ing,” aud gives it as his opinion that the ladies would most probably have carried

it much higher but for the attacks of the friar Conecte. “ This holy man,” he says,

“ travelled from place to place to preach down these monstrous structures ; and

succeeded so well in it that, as the magicians sacrificed their books to the flames

upon the preaching of an apostle, many of tbe women threw down their head-

dresses in the middle of his sermon, and made a bonfire of them within sight of his

pulpit. He was so renowned that he had often a congregation of 20,000 people:

the men placing themselves on the one sioe of his pulpit, and the women ou the

other, that appeared like a forest of cedars with their heads reaching to the clouris.”

t It is not much of a compliment to compare ladies to snails ; but when they wore-

horned head-dresses, the simile was made so often that they must have grown quite

used to it. Endless was the playing by the punsters on these horns. One can

hardly read a line in the satires of the period without coming across such phrases as

“ they deem their horns a hornament,” or “ their horns they have exalted.”