February 15, 1862.]

61

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

THE BIGGEST OF BUTCHER BOYS.

The author of a new life of Shakspeare, Mr. S. W.

Fullom, thinks there is no truth in the late Lord Camp-

bell’s supposition that the great dramatist was employed,

during his youth, in a lawyer’s office. Siiakspeare,

according to his latest biographer, was a butcher’s ap-

prentice, and learned what he knew of legal forms and

technicalities by attending the borough courts of Stratford-

on-Avon, and witnessing those law proceedings in which his

father was often involved. But he is far too minute and

copious in his law slang to have picked it up in that way;

and. besides he shows immense knowledge of sea-slang,

military slang, and many other slangs. His knowledge

cf slang, hi fact, was only part of his knowledge of things

in general, which he either acquired by the study of every-

thing, or possessed by intuition, or else Shakspeare

“ was a medium,” and spirits put universal information

into his head. A great objection to this latter theory is

the height to which his genius towers above the medi-

ocrity. that marks the utterances of the most eminent

“mediums.”

A hypothesis on which the extent of Siiakspeare’s

legal knowledge may be as satisfactorily accounted for as

it can on any other, consists very well with the surmise,

or fact, that he was a butcher-boy. As such he must have

been conversant with sheepskins. We have only to sup-

pose him endowed with the gift of natural clairvoyance, in

order ourselves to see clearly by what means he acquired

his familiarity with the law, and its phraseology. The

sheepskins presented themselves to his prevision in the

state of parchment, and he foresaw all the deeds which

were destined to be engrossed on them.

The clairvoyance of Siiakspeare may be supposed to

have enabled him to look into all manner of things, besides

the sheepskins which lie was accustomed to handle, and

thus obtain that acquaintance with human actions as well

as documentary deeds manifest in his writings. In a state

of trance or ecstacy, having his mind’s eye open, and scenes

of the past, present, or future revealed before it, how

often may Master William Shakspeare have stood

beside a street-door in his native town, with a blue frock

on, and a wooden tray containing a leg of-mutton upon his

shoulder, abstractedly whistling- an old English melody,

and shouting “But-cher!”

PUNCH’S ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

1862. February 6. Thursday. Parliament re-assembled. The first

paragraphs in the Royal Speech (delivered by the Chancellor) and

such portion of the debates as referred to them, demand graver record

than is usually made in these columns. The opening sentences of the

Speech alluded, with but little giace of expression, to the event of

the Fourteenth of December last. Leading speakers in the two Houses

offered tributes to the memory of the departed.

The Earl of Derby said—’

“ In the Prince Consort the Queen has lost the familiar friend, the trusted

counseUor, the never-failing adviser to whom she could look up in every difficulty

and in every emergency, and to whom she did look up with that proud humility

which none but a woman’s heart can know, glorying in the intellectual superiority

of him to whom her own will and her own judgment were freely put in subjection.”

Earl Gkanville said —

“ I can remember no one in any class of life who seemed so fully alive to keep

before him the highest standard of duty. His intellectual faculties and his powers

of conversation were remarkable. But though a man of strong will, conception,

j and character, he never obtruded his sentiments, nor sought to apply any objection

j he might entertain unless desired to do so.”

Earl Russell said: —

“ I happen to know from himself the views which he entertained upon the duty

j Sovereign. He stated to me not many months ago that it was the common

| opinion that there was only one occasion upon which the Sovereign ought to exer-

cise a decided po wer, and that was in the choice of the First Minister of the Crown,

that, in his opinion, was no occasion upon which the Sovereign ought to exercise a

control or to pronounce a decision. One party having resigned power from being

unable to carry on the Government, there was at all times another party to whom

the transfer of power might judiciously be made, and the transfer having once been

made, no matter to what political party the Minister happened to belong, the Sove-

reign was bound to communicate with him in the most confidential and unrestricted

manner.”

Mr. Disraeli said :—

“ The Prince whom we have lost not only was eminent for the fulfilment of his

duty, but it was the fulfilment of the highest duty: and it was the fulfilment of

the highest duty under the most difficult circumstances. Yet, under these circum-

stances, so difficult and so delicate, he elevated even the Throne by the dignity and

purity of his domestic life. He framed, and partly accomplished, a scheme of edu-

cation for the heir of England which proves how completely its august protector

had contemplated the office of an English king. He observed that there was a great

deficiency in our national character, and which, if neglected, might lead to the im-

pairing not only of our social happiness, but even the sources of our public wealth,

and that was a deficiency of culture. But he was not satisfied in detecting the

deficiency, he resolved to supply it. Those who move must change, and those who

change must necessarily disturb and alarm prejudices ; and what lie encountered

was only a demonstration that he was a man superior to his age. Prince Albert

was not a patron. He was not one of those who, by their smiles and by their gold,

reward exceUence or stimulate exertion. His contributions to the cause of pro-

gress and improvement were far more powerful and far more precious. He gave to

it his thought, his time, his toil; he gave to it his life.”

Lord Palmerston said

“ The Right Hon. gentleman, with an eloquence and a feeling which, I am sure,

must excite the sympathy and admiration of those who have heard it, dilated on the

eminent qualities of his late Royal Highness. It is no exaggeration to say that, so

far as the word ‘ perfect ’ can be applied to human imperfection of character, the

Prince deserved the description, because he combined qualities the most eminent,

and sometimes the most different, in a degree which was hardly ever equalled by

anybody in any condition of life. In domestic life he was most exemplary. It is

no exaggeration to say, that the domestic life of the Court has been of the greatest

value to the interests of the country, has, in times of difficulty, tended to cement

the link which unites the people to the Throne, and has rendered the most impor-

tant services to the country. Such being the Prince whom we have lost, we can

easily imagine what must be the grief and the sorrow to her who has lost him.”

Tlie evening was one of funereal oration rather than of debate—the

exceptions are mentioned hereafter. The Addresses were unanimously

voted, and the Houses adjourned early.

Lord Westburt informed us,

That we are at peace with all European powers and “ trust ” to

remain in that pacific condition.

That we have had a “question ” between us and the United States,

which has been satisfactorily settled by the restoration of the seized

men and the disavowal of the “act of violence.”

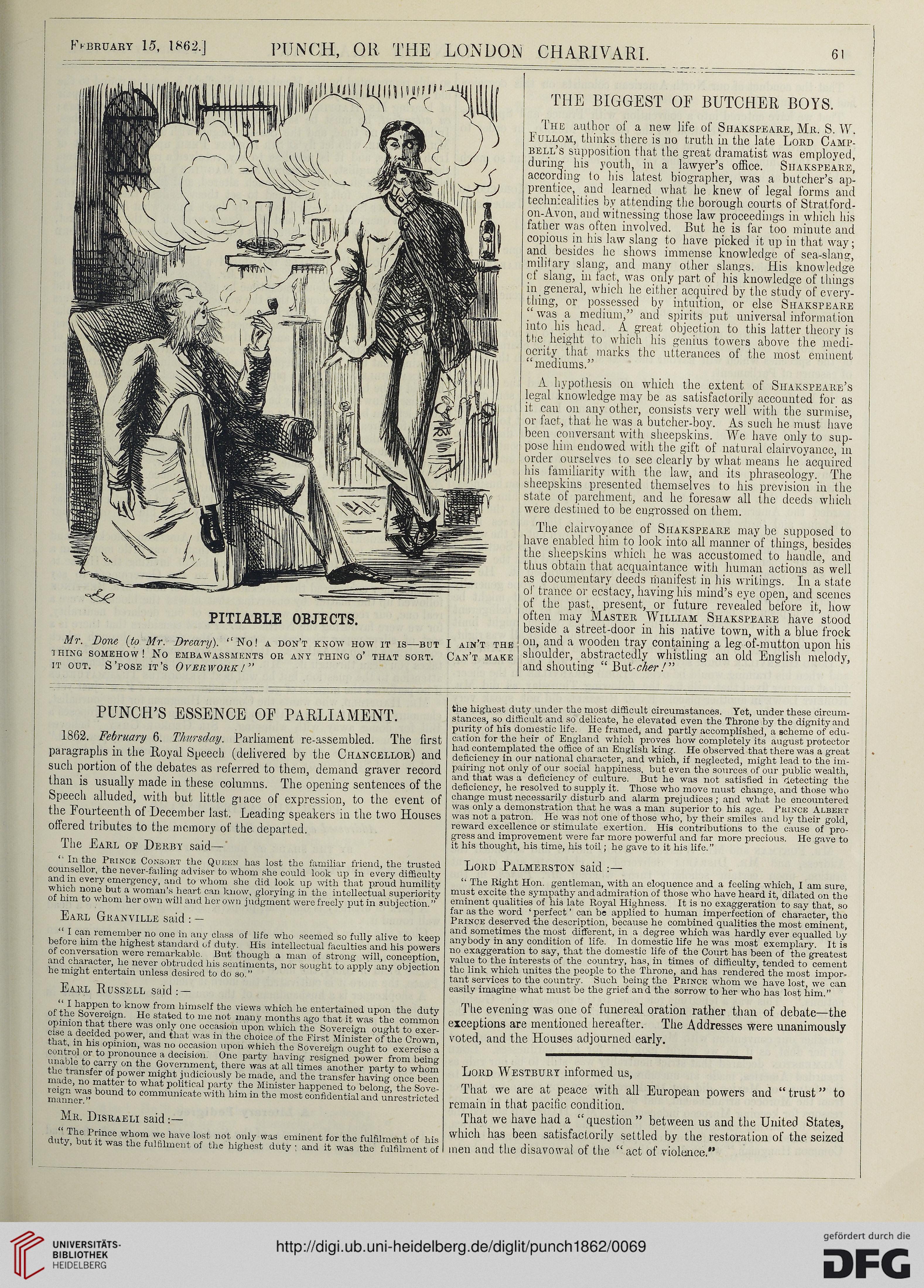

PITIABLE OBJECTS.

Mr. Done (to Mr. Dreary). “No! a don’t know how it is—but I ain’t the

THING SOMEHOW ! No EMBAWASSMENTS OR ANY THING O’ THAT SORT. Can’t MAKE

it out. S ’pose it’s Overwork/ ”

61

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

THE BIGGEST OF BUTCHER BOYS.

The author of a new life of Shakspeare, Mr. S. W.

Fullom, thinks there is no truth in the late Lord Camp-

bell’s supposition that the great dramatist was employed,

during his youth, in a lawyer’s office. Siiakspeare,

according to his latest biographer, was a butcher’s ap-

prentice, and learned what he knew of legal forms and

technicalities by attending the borough courts of Stratford-

on-Avon, and witnessing those law proceedings in which his

father was often involved. But he is far too minute and

copious in his law slang to have picked it up in that way;

and. besides he shows immense knowledge of sea-slang,

military slang, and many other slangs. His knowledge

cf slang, hi fact, was only part of his knowledge of things

in general, which he either acquired by the study of every-

thing, or possessed by intuition, or else Shakspeare

“ was a medium,” and spirits put universal information

into his head. A great objection to this latter theory is

the height to which his genius towers above the medi-

ocrity. that marks the utterances of the most eminent

“mediums.”

A hypothesis on which the extent of Siiakspeare’s

legal knowledge may be as satisfactorily accounted for as

it can on any other, consists very well with the surmise,

or fact, that he was a butcher-boy. As such he must have

been conversant with sheepskins. We have only to sup-

pose him endowed with the gift of natural clairvoyance, in

order ourselves to see clearly by what means he acquired

his familiarity with the law, and its phraseology. The

sheepskins presented themselves to his prevision in the

state of parchment, and he foresaw all the deeds which

were destined to be engrossed on them.

The clairvoyance of Siiakspeare may be supposed to

have enabled him to look into all manner of things, besides

the sheepskins which lie was accustomed to handle, and

thus obtain that acquaintance with human actions as well

as documentary deeds manifest in his writings. In a state

of trance or ecstacy, having his mind’s eye open, and scenes

of the past, present, or future revealed before it, how

often may Master William Shakspeare have stood

beside a street-door in his native town, with a blue frock

on, and a wooden tray containing a leg of-mutton upon his

shoulder, abstractedly whistling- an old English melody,

and shouting “But-cher!”

PUNCH’S ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

1862. February 6. Thursday. Parliament re-assembled. The first

paragraphs in the Royal Speech (delivered by the Chancellor) and

such portion of the debates as referred to them, demand graver record

than is usually made in these columns. The opening sentences of the

Speech alluded, with but little giace of expression, to the event of

the Fourteenth of December last. Leading speakers in the two Houses

offered tributes to the memory of the departed.

The Earl of Derby said—’

“ In the Prince Consort the Queen has lost the familiar friend, the trusted

counseUor, the never-failing adviser to whom she could look up in every difficulty

and in every emergency, and to whom she did look up with that proud humility

which none but a woman’s heart can know, glorying in the intellectual superiority

of him to whom her own will and her own judgment were freely put in subjection.”

Earl Gkanville said —

“ I can remember no one in any class of life who seemed so fully alive to keep

before him the highest standard of duty. His intellectual faculties and his powers

of conversation were remarkable. But though a man of strong will, conception,

j and character, he never obtruded his sentiments, nor sought to apply any objection

j he might entertain unless desired to do so.”

Earl Russell said: —

“ I happen to know from himself the views which he entertained upon the duty

j Sovereign. He stated to me not many months ago that it was the common

| opinion that there was only one occasion upon which the Sovereign ought to exer-

cise a decided po wer, and that was in the choice of the First Minister of the Crown,

that, in his opinion, was no occasion upon which the Sovereign ought to exercise a

control or to pronounce a decision. One party having resigned power from being

unable to carry on the Government, there was at all times another party to whom

the transfer of power might judiciously be made, and the transfer having once been

made, no matter to what political party the Minister happened to belong, the Sove-

reign was bound to communicate with him in the most confidential and unrestricted

manner.”

Mr. Disraeli said :—

“ The Prince whom we have lost not only was eminent for the fulfilment of his

duty, but it was the fulfilment of the highest duty: and it was the fulfilment of

the highest duty under the most difficult circumstances. Yet, under these circum-

stances, so difficult and so delicate, he elevated even the Throne by the dignity and

purity of his domestic life. He framed, and partly accomplished, a scheme of edu-

cation for the heir of England which proves how completely its august protector

had contemplated the office of an English king. He observed that there was a great

deficiency in our national character, and which, if neglected, might lead to the im-

pairing not only of our social happiness, but even the sources of our public wealth,

and that was a deficiency of culture. But he was not satisfied in detecting the

deficiency, he resolved to supply it. Those who move must change, and those who

change must necessarily disturb and alarm prejudices ; and what lie encountered

was only a demonstration that he was a man superior to his age. Prince Albert

was not a patron. He was not one of those who, by their smiles and by their gold,

reward exceUence or stimulate exertion. His contributions to the cause of pro-

gress and improvement were far more powerful and far more precious. He gave to

it his thought, his time, his toil; he gave to it his life.”

Lord Palmerston said

“ The Right Hon. gentleman, with an eloquence and a feeling which, I am sure,

must excite the sympathy and admiration of those who have heard it, dilated on the

eminent qualities of his late Royal Highness. It is no exaggeration to say that, so

far as the word ‘ perfect ’ can be applied to human imperfection of character, the

Prince deserved the description, because he combined qualities the most eminent,

and sometimes the most different, in a degree which was hardly ever equalled by

anybody in any condition of life. In domestic life he was most exemplary. It is

no exaggeration to say, that the domestic life of the Court has been of the greatest

value to the interests of the country, has, in times of difficulty, tended to cement

the link which unites the people to the Throne, and has rendered the most impor-

tant services to the country. Such being the Prince whom we have lost, we can

easily imagine what must be the grief and the sorrow to her who has lost him.”

Tlie evening was one of funereal oration rather than of debate—the

exceptions are mentioned hereafter. The Addresses were unanimously

voted, and the Houses adjourned early.

Lord Westburt informed us,

That we are at peace with all European powers and “ trust ” to

remain in that pacific condition.

That we have had a “question ” between us and the United States,

which has been satisfactorily settled by the restoration of the seized

men and the disavowal of the “act of violence.”

PITIABLE OBJECTS.

Mr. Done (to Mr. Dreary). “No! a don’t know how it is—but I ain’t the

THING SOMEHOW ! No EMBAWASSMENTS OR ANY THING O’ THAT SORT. Can’t MAKE

it out. S ’pose it’s Overwork/ ”