Frederick Sandys

of a brazier, and its radiance shines on her white of the physical man, deeming that the soul ex-

dress and on her pallid face and terrible eyes. She pressed itself in the countenance. Nor did he

clutches with one hand her necklet of coral and treat his subjects as items in a decorative arrange-

turquoise, while from her anguished lips issue ment; he gave us his sitter clearly seen and

irrevocable words of dreadful power. The ex- searchingly rendered, and not his ghost or his

quisite drawing of the hands, the lovely painting of shadow. This may not be the fashionable por-

the pearly shells with which her dark hair is adorned, traiture of to-day, but certainly some of the greatest

and the masterly treatment of the other accessories portraits of all time have been painted on this

need not be enlarged on here, but it may be inter- basis.

esting to note (as characteristic of the artist) that Some of these portraits are oil - paintings, the

though the subject is chosen from a classic myth, superb Mrs. Lewis and Mrs. Anderson Rose among

the informing spirit is rather that of Gothic romance. them; others are chalk drawings, and with these

The picture is conceived as Cranach or as Van der drawings we come to the third phase of Sandys'

Goes might have conceived it; in treatment it is akin art. But whether they are in oils or in chalks, they

to the work of the early painters of the Teutonic are alike in their characteristics. The portraits of

schools, and the brooding intensity, the dark men are virile and forceful and redolent of character,

overwhelming horror that characterise the work as the women serene, gracious and graceful, and the

a whole inevitably recall the hopeless tragedy that children as delicious and lovable as any in the

pervades the stern sagas of the

North. Altogether it is a mag-

nificent conception fitly ren- ppfiaWPWli" " \^mm*wwmmmg^m^m^mm^mr^^^^^^

dered, a work worthy to rank

amongst the finest imagina-

tive creations painted in Eng-

land in the nineteenth century.

It is always interesting to

discuss the differing ideals of

portraiture, to consider the ^K£ls%JL

inspiration of Holbein as con-

trasted with that of Hals, of

Velasquez as compared with

Watts; and it would be far

from unprofitable to treat at

some length of Sandys' unique

achievements in this field of

art, and to endeavour to see

(if space did but permit) just

where as a portrait painter he

must be placed. That he

painted some notable portraits

is well known, and it is equally

well known that the same

searching after definite truth

that we find in his other work

is to be found in these can-

vases, which are as far from I ' . ' *

superficiality as from inac-

curacy, while they are as fresh,

as vivid, as individual and as

complete as are the portraits HNdtf *

of Holbein himself. Sandys

was not concerned to make a

portrait the likeness of a man's

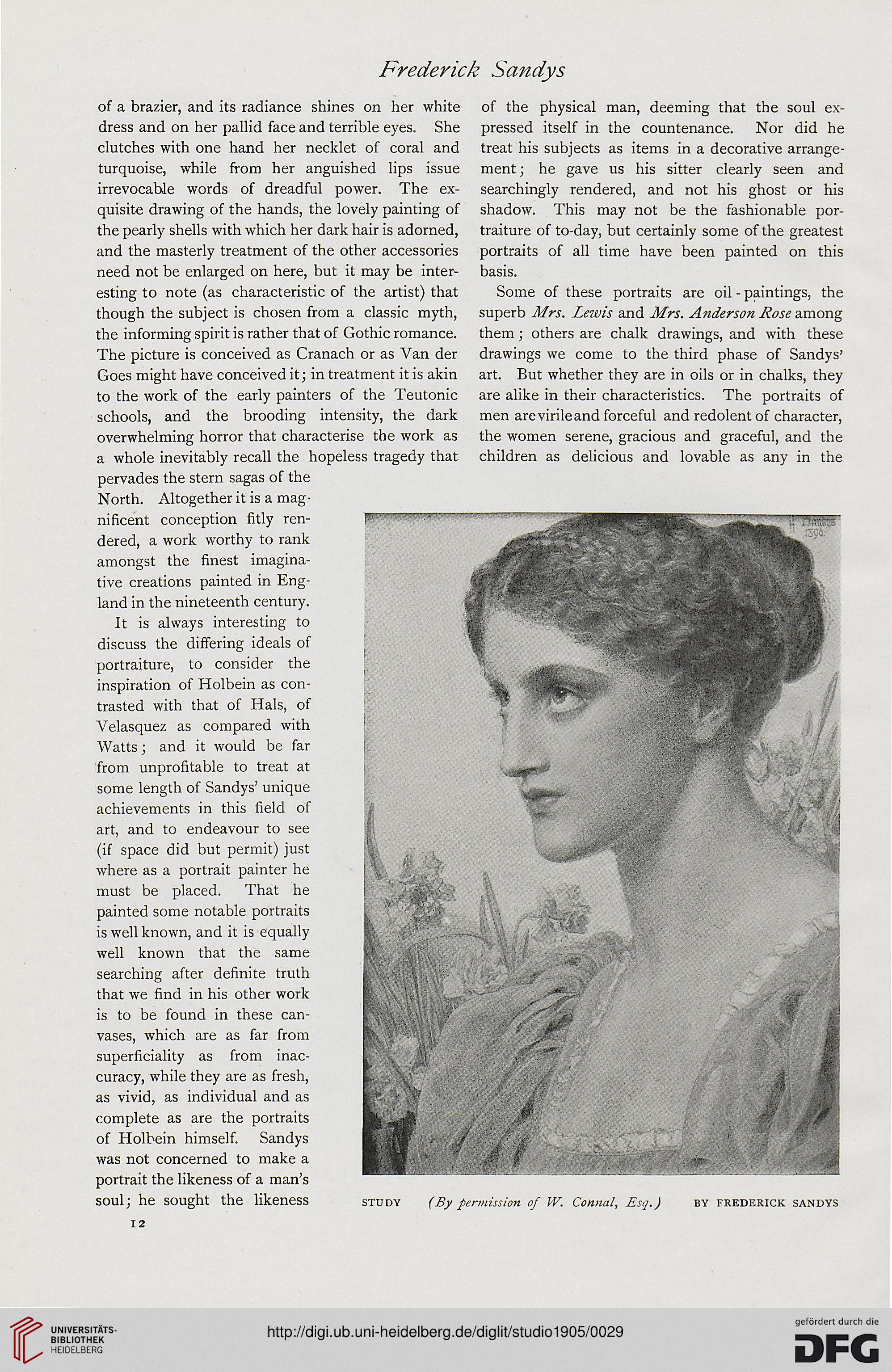

SOUl; he sought the likeness STUDY (By permission of W. Connal, Esq.) BY FREDERICK SANDYS

of a brazier, and its radiance shines on her white of the physical man, deeming that the soul ex-

dress and on her pallid face and terrible eyes. She pressed itself in the countenance. Nor did he

clutches with one hand her necklet of coral and treat his subjects as items in a decorative arrange-

turquoise, while from her anguished lips issue ment; he gave us his sitter clearly seen and

irrevocable words of dreadful power. The ex- searchingly rendered, and not his ghost or his

quisite drawing of the hands, the lovely painting of shadow. This may not be the fashionable por-

the pearly shells with which her dark hair is adorned, traiture of to-day, but certainly some of the greatest

and the masterly treatment of the other accessories portraits of all time have been painted on this

need not be enlarged on here, but it may be inter- basis.

esting to note (as characteristic of the artist) that Some of these portraits are oil - paintings, the

though the subject is chosen from a classic myth, superb Mrs. Lewis and Mrs. Anderson Rose among

the informing spirit is rather that of Gothic romance. them; others are chalk drawings, and with these

The picture is conceived as Cranach or as Van der drawings we come to the third phase of Sandys'

Goes might have conceived it; in treatment it is akin art. But whether they are in oils or in chalks, they

to the work of the early painters of the Teutonic are alike in their characteristics. The portraits of

schools, and the brooding intensity, the dark men are virile and forceful and redolent of character,

overwhelming horror that characterise the work as the women serene, gracious and graceful, and the

a whole inevitably recall the hopeless tragedy that children as delicious and lovable as any in the

pervades the stern sagas of the

North. Altogether it is a mag-

nificent conception fitly ren- ppfiaWPWli" " \^mm*wwmmmg^m^m^mm^mr^^^^^^

dered, a work worthy to rank

amongst the finest imagina-

tive creations painted in Eng-

land in the nineteenth century.

It is always interesting to

discuss the differing ideals of

portraiture, to consider the ^K£ls%JL

inspiration of Holbein as con-

trasted with that of Hals, of

Velasquez as compared with

Watts; and it would be far

from unprofitable to treat at

some length of Sandys' unique

achievements in this field of

art, and to endeavour to see

(if space did but permit) just

where as a portrait painter he

must be placed. That he

painted some notable portraits

is well known, and it is equally

well known that the same

searching after definite truth

that we find in his other work

is to be found in these can-

vases, which are as far from I ' . ' *

superficiality as from inac-

curacy, while they are as fresh,

as vivid, as individual and as

complete as are the portraits HNdtf *

of Holbein himself. Sandys

was not concerned to make a

portrait the likeness of a man's

SOUl; he sought the likeness STUDY (By permission of W. Connal, Esq.) BY FREDERICK SANDYS