Paul Schultze-Naumbtirg

The first difficulty to be encountered was of an

external and technical character. Oil-colour, treated

as a thick paste and laid on without much manipu-

lation, had proved the best medium for plein-air

subjects, but here it no longer sufficed. In the

old masters interior effects could be noted that

were pleasing to the eye, but their constitution

was a riddle. With the energy that he brought to

every task, Schultze set himself to re-discover the

technical methods of past ages, and to experiment

scientifically with all the new processes that our

modern industry provides. His intimate study

of the old masters, particularly those of the

early Renaissance, gave him the key to a long-

sought-for secret. The visible picture of nature,

even in the full witchery of some special

mood, when reproduced on the canvas certainly

repeated the impression made upon the eye ; but

it did not give the mental sensation that the vision

of nature had evoked. He now learned from the

old masters that a piece of natural beauty must be

translated into pictorial beauty, in order that we

may experience, at sight of the latter, what we ex-

perienced on beholding the former. And this

pictorial beauty follows the same laws that in

applied art regulate the " pleasing" or the

" repellent " sensation. Thus from the imaginative

conception was evolved the decorative conception.

His picture Schbnburg (page 214) may serve

as an example to show how true to nature were

the pictures that he based on decorative considera-

tions, just because they did not copy the beauties

of nature, but created them anew for the purposes

of the picture. The wall-picture became Schultze's

special task.

The " decorative movement" in Germany

threatens likewise to become over-externalised and

superficialised. Imitation of the foreign or of the

old-fashioned, on the one side, and on the other, a

restless striving after the novel, the unusual, the

eccentric, have much distorted its original character.

Schultze-Naumburg has been saved from these

dangers by the last new development of his artistic

personality. In his practice of decorative art he

had discovered what he had long suspected in the

case of pure art—namely, in what intimate relation-

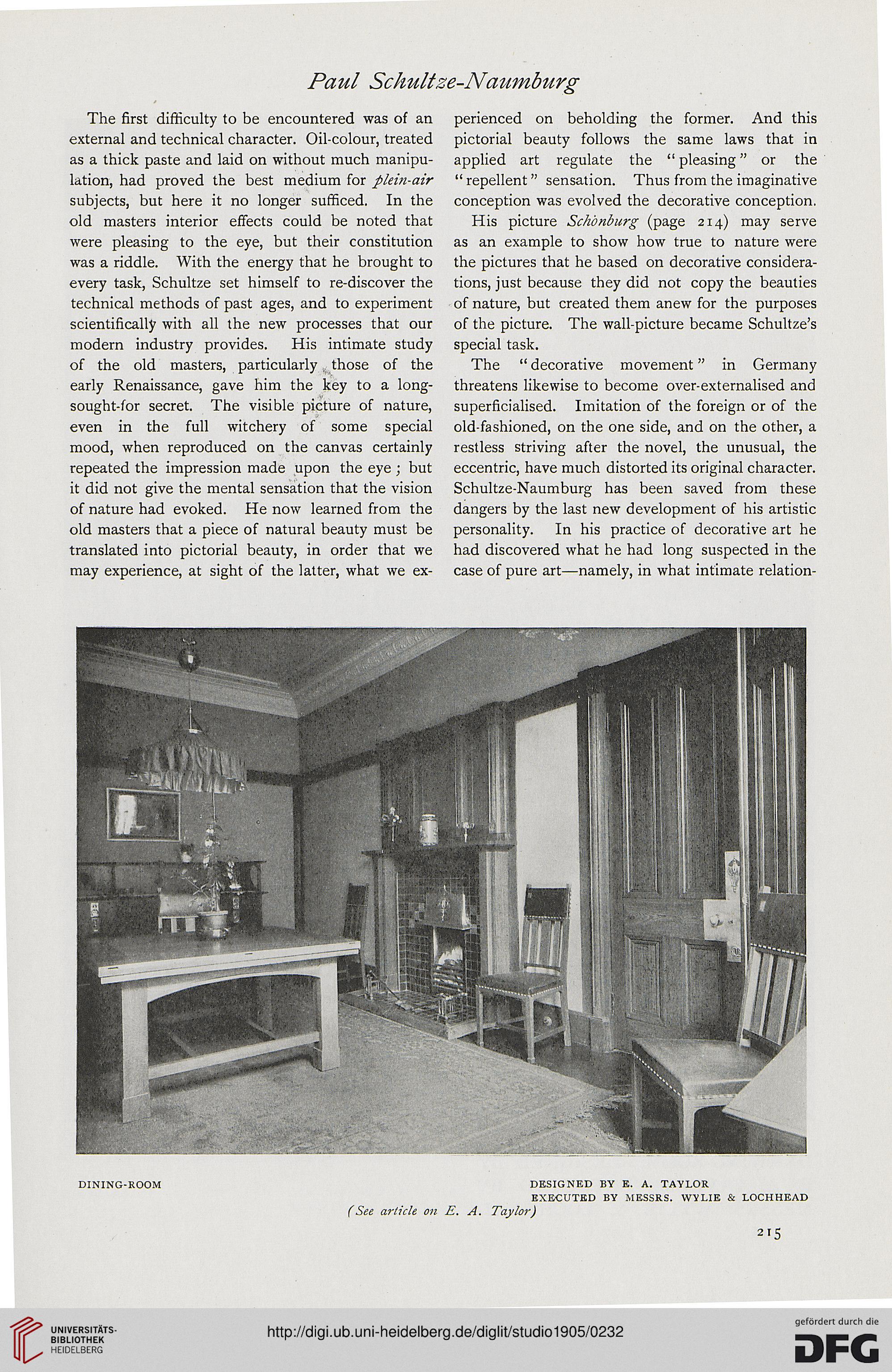

The first difficulty to be encountered was of an

external and technical character. Oil-colour, treated

as a thick paste and laid on without much manipu-

lation, had proved the best medium for plein-air

subjects, but here it no longer sufficed. In the

old masters interior effects could be noted that

were pleasing to the eye, but their constitution

was a riddle. With the energy that he brought to

every task, Schultze set himself to re-discover the

technical methods of past ages, and to experiment

scientifically with all the new processes that our

modern industry provides. His intimate study

of the old masters, particularly those of the

early Renaissance, gave him the key to a long-

sought-for secret. The visible picture of nature,

even in the full witchery of some special

mood, when reproduced on the canvas certainly

repeated the impression made upon the eye ; but

it did not give the mental sensation that the vision

of nature had evoked. He now learned from the

old masters that a piece of natural beauty must be

translated into pictorial beauty, in order that we

may experience, at sight of the latter, what we ex-

perienced on beholding the former. And this

pictorial beauty follows the same laws that in

applied art regulate the " pleasing" or the

" repellent " sensation. Thus from the imaginative

conception was evolved the decorative conception.

His picture Schbnburg (page 214) may serve

as an example to show how true to nature were

the pictures that he based on decorative considera-

tions, just because they did not copy the beauties

of nature, but created them anew for the purposes

of the picture. The wall-picture became Schultze's

special task.

The " decorative movement" in Germany

threatens likewise to become over-externalised and

superficialised. Imitation of the foreign or of the

old-fashioned, on the one side, and on the other, a

restless striving after the novel, the unusual, the

eccentric, have much distorted its original character.

Schultze-Naumburg has been saved from these

dangers by the last new development of his artistic

personality. In his practice of decorative art he

had discovered what he had long suspected in the

case of pure art—namely, in what intimate relation-