T. L. Shoosmith's IVater-colours

circuitous route, every one of them nervous and

none of them mechanical. On the other hand, as

with Mr. Shoosmith, the artist may arrive at his

result directly. Directness is not essential to

spontaneity or the reverse, and it is possible to

paint a thing directly without it having any spon-

taneity in it. The secret of attaining that quality

is the secret of the artist knowing exactly what he

wants to do, and he may not want to do a simple

thing, but something which is built up, one kind of

quality willingly lost to make a foundation for

another. No one shall say that any particular

method in water-colour painting is wrong. In some

ways it is the most fascinating of mediums ; it is less

dependent on any particular method than almost

any other medium, and having once learnt to control

the running water any painter may find in it qualities

for him alone. Style comes from the reconciliation

of the restless vision of the artist with its hard-and-

fast limitations ; its beauty lies in the evidence that

virtuosity has schooled it. To use water-colours

for a purpose purely of imitation, and not to wait

on its waywardness and' to avail himself of that way-

wardness for accidental effect, is for the artist to

prove himself holding a false ideal of its practice,

and to be dead to a beauty in it which will teach

him beauty, water and colour in themselves holding

such delicate secrets as in the art from Girtin to

Whistler have been the dream of its masters.

The essential qualities of water-colour painting

are perhaps even less understood by the lay mind

in art than the qualities of good oil painting; it

seems difficult for the layman in these matters to

appreciate and reconcile the variety of treatment

of which it is capable with his unsophisticated

vision of nature. Unable to disembarrass his

mind from an ideal of only imitative success,

there is often lost upon him all the accidental charm

which is its characteristic. Rightly understood, it

is less an imitative medium than any other, and

nowhere in art does mere imitation set the highest

standard. Its peculiar qualities render it par-

ticularly sensitive to individual treatment, so that

with one man it is a means towards realism,

with another an excuse for fantasy, and no medium

can become more personal to the artist or give

more intimate expression to his peculiar vision.

Upon whatever terms a painter stands with

nature, if he is fortunate enough in his art to

stand upon any at all with her and retain a

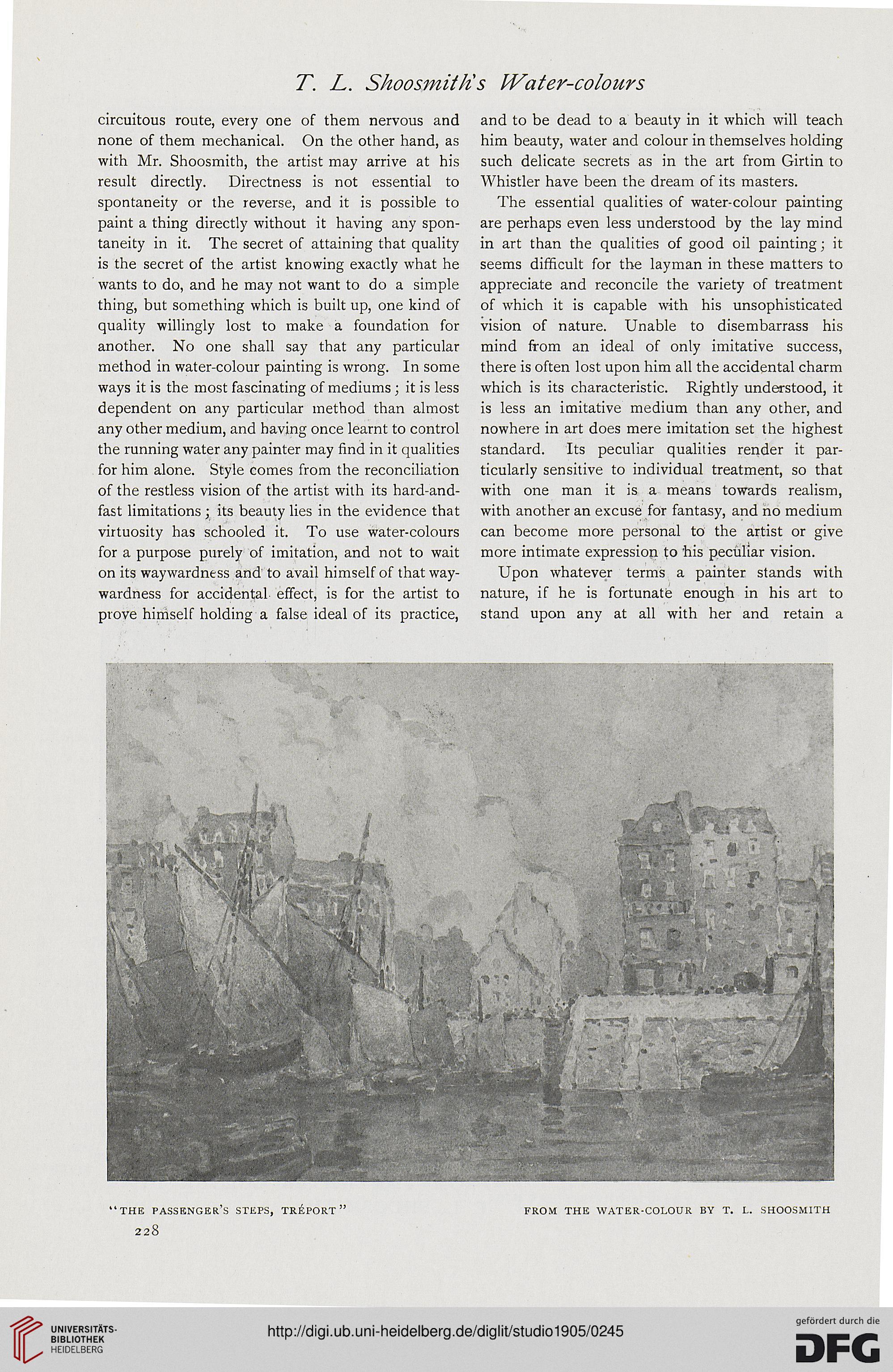

'the passenger's steps, treport "

228

from the water-colour by t. l. shoosmith

circuitous route, every one of them nervous and

none of them mechanical. On the other hand, as

with Mr. Shoosmith, the artist may arrive at his

result directly. Directness is not essential to

spontaneity or the reverse, and it is possible to

paint a thing directly without it having any spon-

taneity in it. The secret of attaining that quality

is the secret of the artist knowing exactly what he

wants to do, and he may not want to do a simple

thing, but something which is built up, one kind of

quality willingly lost to make a foundation for

another. No one shall say that any particular

method in water-colour painting is wrong. In some

ways it is the most fascinating of mediums ; it is less

dependent on any particular method than almost

any other medium, and having once learnt to control

the running water any painter may find in it qualities

for him alone. Style comes from the reconciliation

of the restless vision of the artist with its hard-and-

fast limitations ; its beauty lies in the evidence that

virtuosity has schooled it. To use water-colours

for a purpose purely of imitation, and not to wait

on its waywardness and' to avail himself of that way-

wardness for accidental effect, is for the artist to

prove himself holding a false ideal of its practice,

and to be dead to a beauty in it which will teach

him beauty, water and colour in themselves holding

such delicate secrets as in the art from Girtin to

Whistler have been the dream of its masters.

The essential qualities of water-colour painting

are perhaps even less understood by the lay mind

in art than the qualities of good oil painting; it

seems difficult for the layman in these matters to

appreciate and reconcile the variety of treatment

of which it is capable with his unsophisticated

vision of nature. Unable to disembarrass his

mind from an ideal of only imitative success,

there is often lost upon him all the accidental charm

which is its characteristic. Rightly understood, it

is less an imitative medium than any other, and

nowhere in art does mere imitation set the highest

standard. Its peculiar qualities render it par-

ticularly sensitive to individual treatment, so that

with one man it is a means towards realism,

with another an excuse for fantasy, and no medium

can become more personal to the artist or give

more intimate expression to his peculiar vision.

Upon whatever terms a painter stands with

nature, if he is fortunate enough in his art to

stand upon any at all with her and retain a

'the passenger's steps, treport "

228

from the water-colour by t. l. shoosmith