STUDIO-TALK

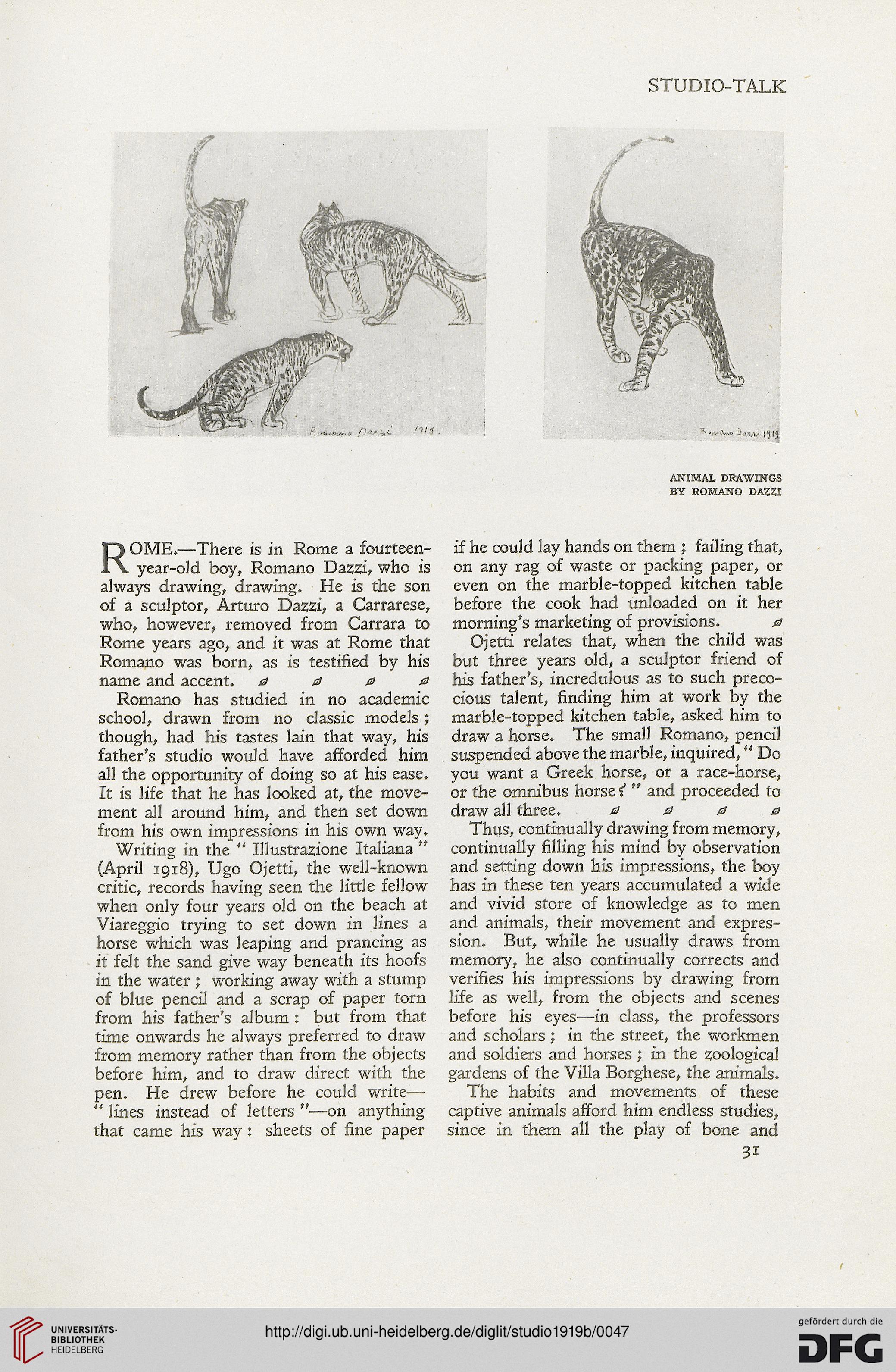

ANIMAL DRAWINGS

BY ROMANO DAZZI

ROME.—There is in Rome a fourteen-

year-old boy, Romano Dazzi, who is

always drawing, drawing. He is the son

of a sculptor, Arturo Dazzi, a Carrarese,

who, however, removed from Carrara to

Rome years ago, and it was at Rome that

Romano was born, as is testified by his

name and accent, 0000

Romano has studied in no academic

school, drawn from no classic models;

though, had his tastes lain that way, his

father's studio would have afforded him

all the opportunity of doing so at his ease.

It is life that he has looked at, the move-

ment all around him, and then set down

from his own impressions in his own way.

Writing in the “ Illustrazione Italiana ”

(April 1918), Ugo Ojetti, the well-known

critic, records having seen the little fellow

when only four years old on the beach at

Viareggio trying to set down in lines a

horse which was leaping and prancing as

it felt the sand give way beneath its hoofs

in the water ; working away with a stump

of blue pencil and a scrap of paper torn

from his father's album : but from that

time onwards he always preferred to draw

from memory rather than from the objects

before him, and to draw direct with the

pen. He drew before he could write—

“ lines instead of letters "—on anything

that came his way : sheets of fine paper

if he could lay hands on them ; failing that,

on any rag of waste or packing paper, or

even on the marble-topped kitchen table

before the cook had unloaded on it her

morning's marketing of provisions. 0

Ojetti relates that, when the child was

but three years old, a sculptor friend of

his father's, incredulous as to such preco-

cious talent, finding him at work by the

marble-topped kitchen table, asked him to

draw a horse. The small Romano, pencil

suspended above the marble, inquired, “ Do

you want a Greek horse, or a race-horse,

or the omnibus horse i " and proceeded to

draw all three. 0000

Thus, continually drawing from memory,

continually filling his mind by observation

and setting down his impressions, the boy

has in these ten years accumulated a wide

and vivid store of knowledge as to men

and animals, their movement and expres-

sion. But, while he usually draws from

memory, he also continually corrects and

verifies his impressions by drawing from

life as well, from the objects and scenes

before his eyes—in class, the professors

and scholars; in the street, the workmen

and soldiers and horses; in the zoological

gardens of the Villa Borghese, the animals.

The habits and movements of these

captive animals afford him endless studies,

since in them all the play of bone and

31

ANIMAL DRAWINGS

BY ROMANO DAZZI

ROME.—There is in Rome a fourteen-

year-old boy, Romano Dazzi, who is

always drawing, drawing. He is the son

of a sculptor, Arturo Dazzi, a Carrarese,

who, however, removed from Carrara to

Rome years ago, and it was at Rome that

Romano was born, as is testified by his

name and accent, 0000

Romano has studied in no academic

school, drawn from no classic models;

though, had his tastes lain that way, his

father's studio would have afforded him

all the opportunity of doing so at his ease.

It is life that he has looked at, the move-

ment all around him, and then set down

from his own impressions in his own way.

Writing in the “ Illustrazione Italiana ”

(April 1918), Ugo Ojetti, the well-known

critic, records having seen the little fellow

when only four years old on the beach at

Viareggio trying to set down in lines a

horse which was leaping and prancing as

it felt the sand give way beneath its hoofs

in the water ; working away with a stump

of blue pencil and a scrap of paper torn

from his father's album : but from that

time onwards he always preferred to draw

from memory rather than from the objects

before him, and to draw direct with the

pen. He drew before he could write—

“ lines instead of letters "—on anything

that came his way : sheets of fine paper

if he could lay hands on them ; failing that,

on any rag of waste or packing paper, or

even on the marble-topped kitchen table

before the cook had unloaded on it her

morning's marketing of provisions. 0

Ojetti relates that, when the child was

but three years old, a sculptor friend of

his father's, incredulous as to such preco-

cious talent, finding him at work by the

marble-topped kitchen table, asked him to

draw a horse. The small Romano, pencil

suspended above the marble, inquired, “ Do

you want a Greek horse, or a race-horse,

or the omnibus horse i " and proceeded to

draw all three. 0000

Thus, continually drawing from memory,

continually filling his mind by observation

and setting down his impressions, the boy

has in these ten years accumulated a wide

and vivid store of knowledge as to men

and animals, their movement and expres-

sion. But, while he usually draws from

memory, he also continually corrects and

verifies his impressions by drawing from

life as well, from the objects and scenes

before his eyes—in class, the professors

and scholars; in the street, the workmen

and soldiers and horses; in the zoological

gardens of the Villa Borghese, the animals.

The habits and movements of these

captive animals afford him endless studies,

since in them all the play of bone and

31