GERALD BROCKHURST'S PAINTINGS AND DRAWINGS

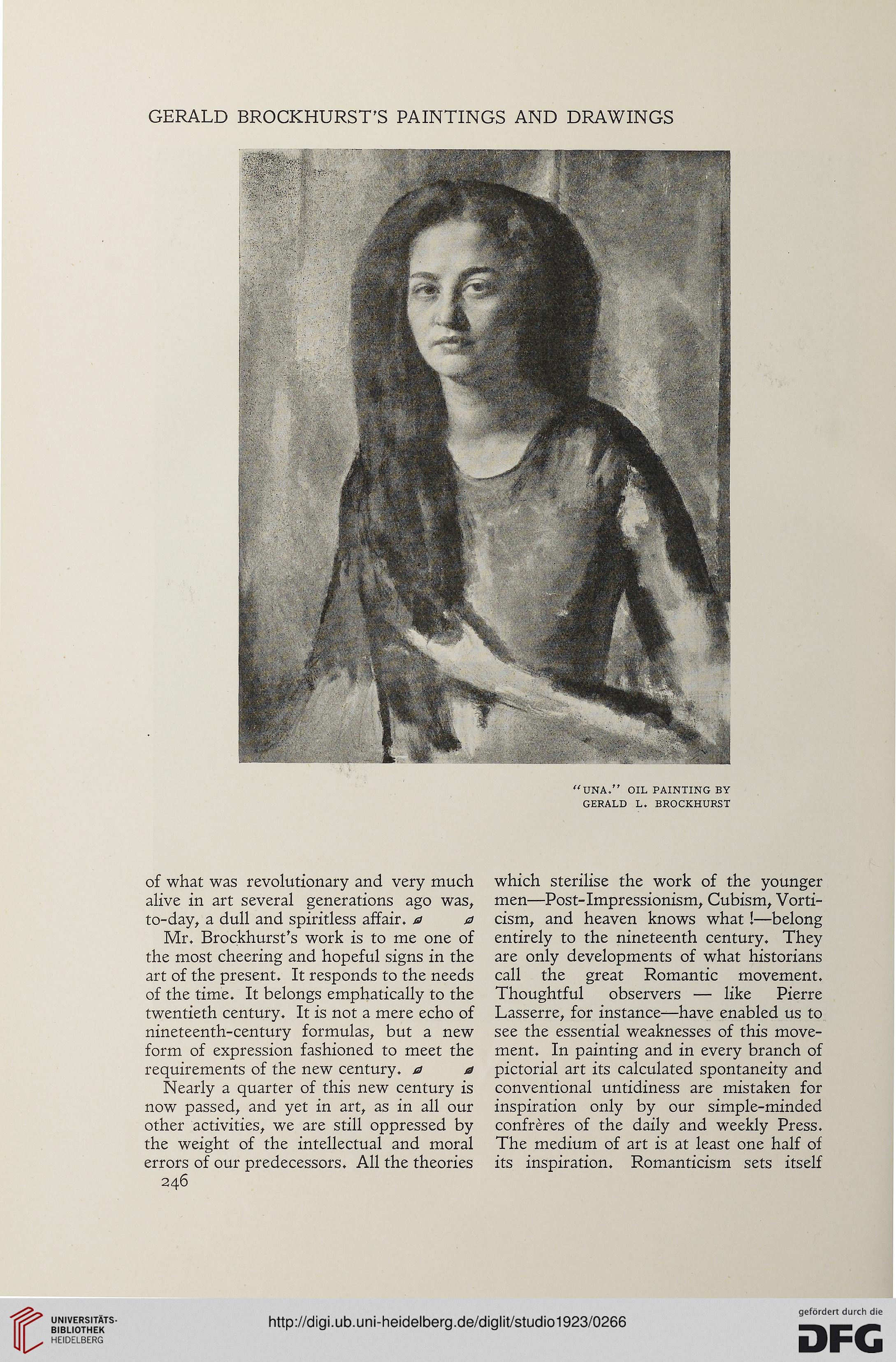

“UNA.” OIL PAINTING BY

GERALD L. BROCKHURST

of what was revolutionary and very much

alive in art several generations ago was,

to-day, a dull and spiritless affair, a a

Mr. Brockhurst's work is to me one of

the most cheering and hopeful signs in the

art of the present. It responds to the needs

of the time. It belongs emphatically to the

twentieth century. It is not a mere echo of

nineteenth-century formulas, but a new

form of expression fashioned to meet the

requirements of the new century, a a

Nearly a quarter of this new century is

now passed, and yet in art, as in all our

other activities, we are still oppressed by

the weight of the intellectual and moral

errors of our predecessors. All the theories

246

which sterilise the work of the younger

men—Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Vorti-

cism, and heaven knows what!—belong

entirely to the nineteenth century. They

are only developments of what historians

call the great Romantic movement.

Thoughtful observers — like Pierre

Lasserre, for instance—have enabled us to

see the essential weaknesses of this move-

ment. In painting and in every branch of

pictorial art its calculated spontaneity and

conventional untidiness are mistaken for

inspiration only by our simple-minded

confreres of the daily and weekly Press.

The medium of art is at least one half of

its inspiration. Romanticism sets itself

“UNA.” OIL PAINTING BY

GERALD L. BROCKHURST

of what was revolutionary and very much

alive in art several generations ago was,

to-day, a dull and spiritless affair, a a

Mr. Brockhurst's work is to me one of

the most cheering and hopeful signs in the

art of the present. It responds to the needs

of the time. It belongs emphatically to the

twentieth century. It is not a mere echo of

nineteenth-century formulas, but a new

form of expression fashioned to meet the

requirements of the new century, a a

Nearly a quarter of this new century is

now passed, and yet in art, as in all our

other activities, we are still oppressed by

the weight of the intellectual and moral

errors of our predecessors. All the theories

246

which sterilise the work of the younger

men—Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Vorti-

cism, and heaven knows what!—belong

entirely to the nineteenth century. They

are only developments of what historians

call the great Romantic movement.

Thoughtful observers — like Pierre

Lasserre, for instance—have enabled us to

see the essential weaknesses of this move-

ment. In painting and in every branch of

pictorial art its calculated spontaneity and

conventional untidiness are mistaken for

inspiration only by our simple-minded

confreres of the daily and weekly Press.

The medium of art is at least one half of

its inspiration. Romanticism sets itself