Studio- Talk

NEW YORK.—In one of the smaller

galleries in New York, last season,

an exhibition of paintings was held

concerning which there was more than

the usual divergence of opinion. To some persons

these paintings harked only of tradition, while to

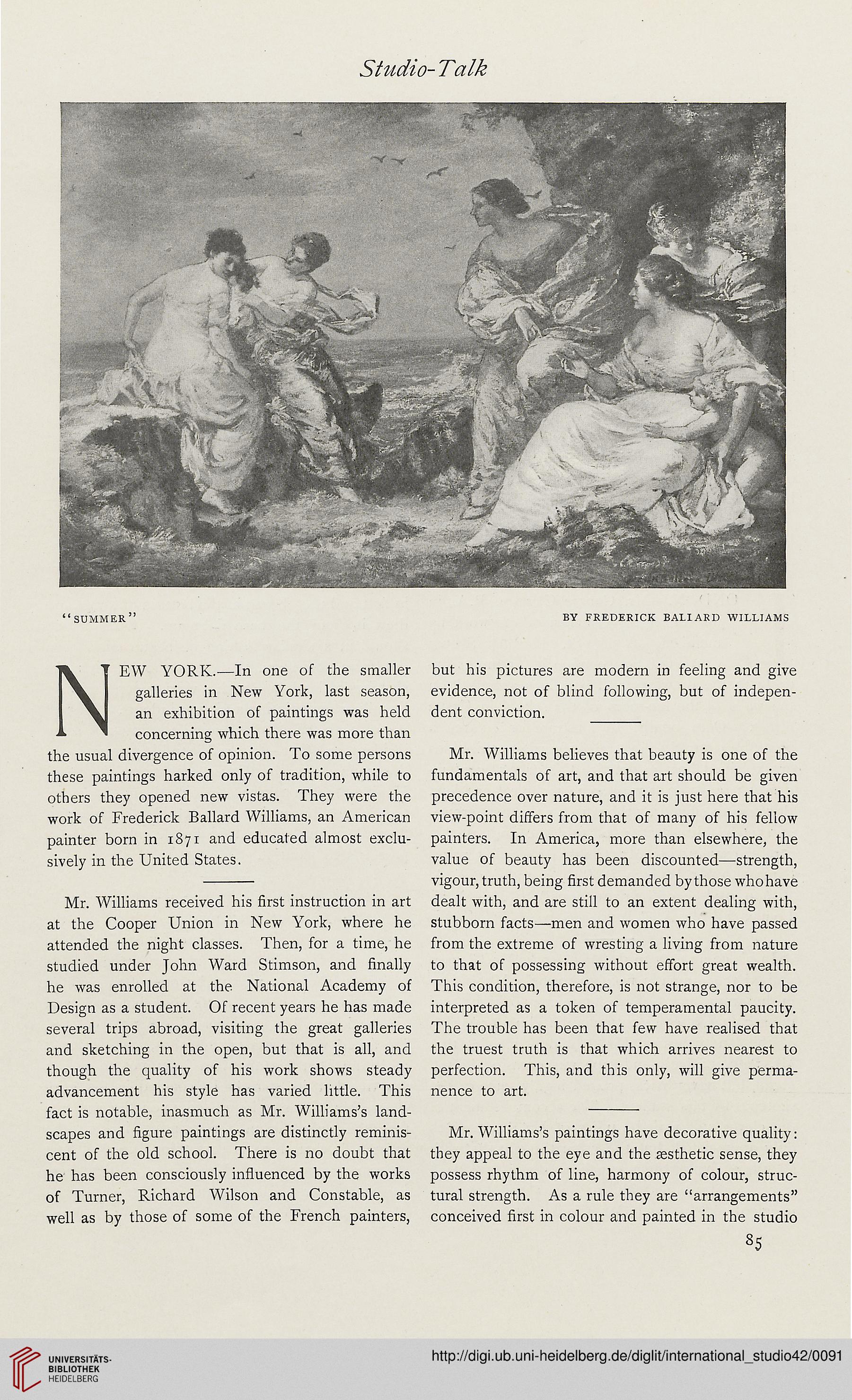

others they opened new vistas. They were the

work of Frederick Ballard Williams, an American

painter bom in 1871 and educated almost exclu-

sively in the United States.

Mr. Williams received his first instruction in art

at the Cooper Union in New York, where he

attended the night classes. Then, for a time, he

studied under John Ward Stimson, and finally

he was enrolled at the National Academy of

Design as a student. Of recent years he has made

several trips abroad, visiting the great galleries

and sketching in the open, but that is all, and

though the quality of his work shows steady

advancement his style has varied little. This

fact is notable, inasmuch as Mr. Williams's land-

scapes and figure paintings are distinctly reminis-

cent of the old school. There is no doubt that

he has been consciously influenced by the works

of Turner, Richard Wilson and Constable, as

well as by those of some of the French painters,

but his pictures are modern in feeling and give

evidence, not of blind following, but of indepen-

dent conviction.

Mr. Williams believes that beauty is one of the

fundamentals of art, and that art should be given

precedence over nature, and it is just here that his

view-point differs from that of many of his fellow

painters. In America, more than elsewhere, the

value of beauty has been discounted—strength,

vigour, truth, being first demanded by those who have

dealt with, and are still to an extent dealing with,

stubborn facts—men and women who have passed

from the extreme of wresting a living from nature

to that of possessing without effort great wealth.

This condition, therefore, is not strange, nor to be

interpreted as a token of temperamental paucity.

The trouble has been that few have realised that

the truest truth is that which arrives nearest to

perfection. This, and this only, will give perma-

nence to art.

Mr. Williams's paintings have decorative quality:

they appeal to the eye and the esthetic sense, they

possess rhythm of line, harmony of colour, struc-

tural strength. As a rule they are "arrangements"

conceived first in colour and painted in the studio

85

NEW YORK.—In one of the smaller

galleries in New York, last season,

an exhibition of paintings was held

concerning which there was more than

the usual divergence of opinion. To some persons

these paintings harked only of tradition, while to

others they opened new vistas. They were the

work of Frederick Ballard Williams, an American

painter bom in 1871 and educated almost exclu-

sively in the United States.

Mr. Williams received his first instruction in art

at the Cooper Union in New York, where he

attended the night classes. Then, for a time, he

studied under John Ward Stimson, and finally

he was enrolled at the National Academy of

Design as a student. Of recent years he has made

several trips abroad, visiting the great galleries

and sketching in the open, but that is all, and

though the quality of his work shows steady

advancement his style has varied little. This

fact is notable, inasmuch as Mr. Williams's land-

scapes and figure paintings are distinctly reminis-

cent of the old school. There is no doubt that

he has been consciously influenced by the works

of Turner, Richard Wilson and Constable, as

well as by those of some of the French painters,

but his pictures are modern in feeling and give

evidence, not of blind following, but of indepen-

dent conviction.

Mr. Williams believes that beauty is one of the

fundamentals of art, and that art should be given

precedence over nature, and it is just here that his

view-point differs from that of many of his fellow

painters. In America, more than elsewhere, the

value of beauty has been discounted—strength,

vigour, truth, being first demanded by those who have

dealt with, and are still to an extent dealing with,

stubborn facts—men and women who have passed

from the extreme of wresting a living from nature

to that of possessing without effort great wealth.

This condition, therefore, is not strange, nor to be

interpreted as a token of temperamental paucity.

The trouble has been that few have realised that

the truest truth is that which arrives nearest to

perfection. This, and this only, will give perma-

nence to art.

Mr. Williams's paintings have decorative quality:

they appeal to the eye and the esthetic sense, they

possess rhythm of line, harmony of colour, struc-

tural strength. As a rule they are "arrangements"

conceived first in colour and painted in the studio

85