Japanese Art and Artists of To-day.—IV. Wood and Ivory Carving

Japanese Exhibition at Shepherd's Bush have

received from the general public, perhaps, the

highest praise next to that of embroidery, they do

not very much appeal to the Japanese. Because of

this demand in the West, regardless of its artistic

merit, we have an abundance of mediocre artists in

this line of work. It is maintained by many that a

numberof years must elapse before the ivory carvings

will find favour in Japan, and win an honoured

place as an ornament on a tokonoma, for as sup-

plied to the West they are by no means'expressive

of the saving characteristics of Japanese carving.

On the other hand, there are comparatively few

sculptors in wood in Japan, owing to the fact that

they have not yet found a market for their pro-

ductions outside of Japan, while the demand at

home is limited to very choice creations. One

will appreciate this fact more deeply when one

realises that in Japanese houses only on a tokonoma

—a special place slightly raised from the floor and

cut into the wall as an alcove—are art objects

placed, and generally one at a time. Take, for in-

stance, the wooden statue of Sugawara Muhizane, by

Yonehara, already referred to. In a Japanese home

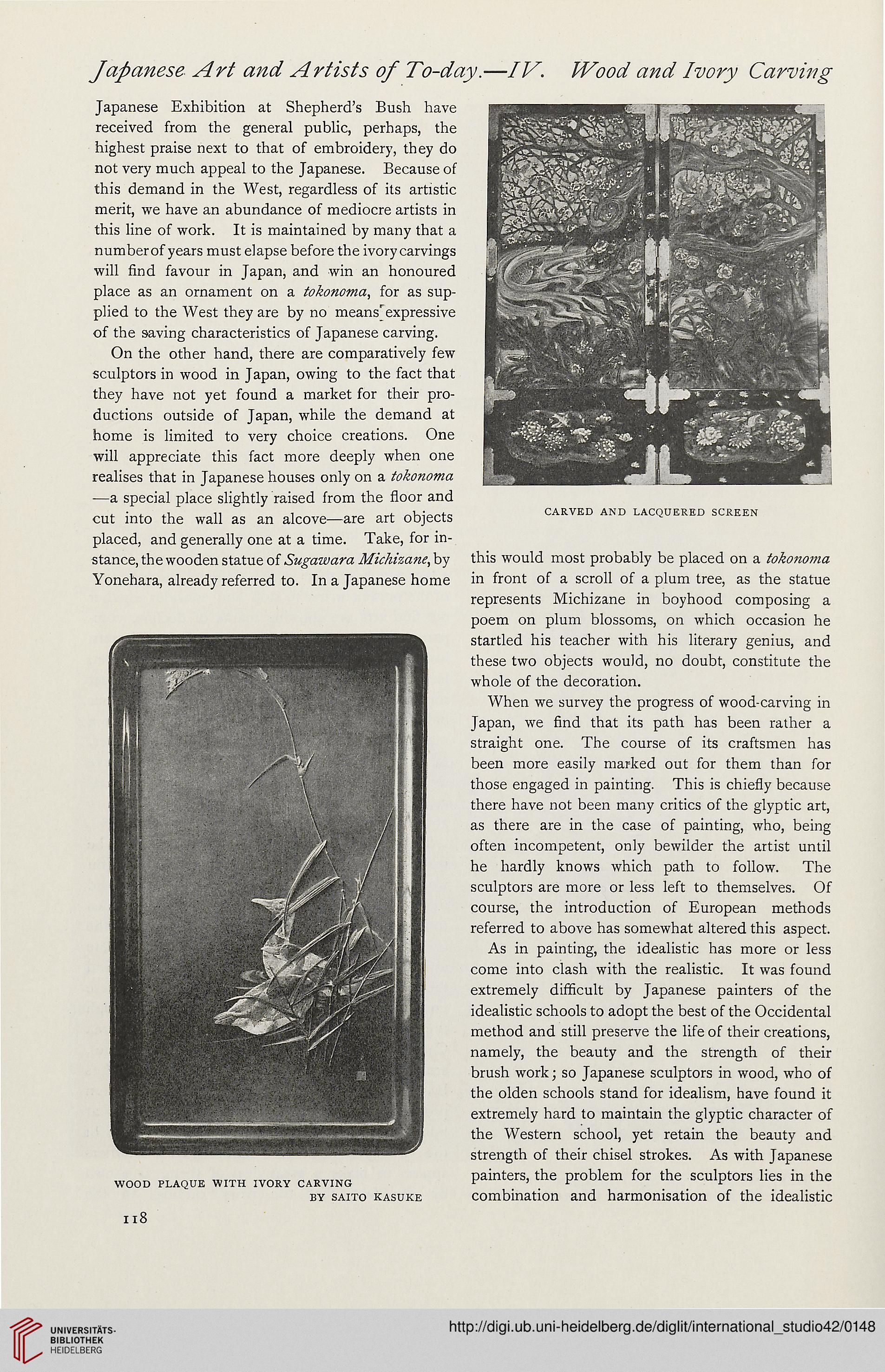

WOOD PLAQUE WITH IVORY CARVING

BY SAITO KASUKE

Il8

CARVED AND LACQUERED SCREEN

this would most probably be placed on a tokonoma

in front of a scroll of a plum tree, as the statue

represents Michizane in boyhood composing a

poem on plum blossoms, on which occasion he

startled his teacher with his literary genius, and

these two objects would, no doubt, constitute the

whole of the decoration.

When we survey the progress of wood-carving in

Japan, we find that its path has been rather a

straight one. The course of its craftsmen has

been more easily marked out for them than for

those engaged in painting. This is chiefly because

there have not been many critics of the glyptic art,

as there are in the case of painting, who, being

often incompetent, only bewilder the artist until

he hardly knows which path to follow. The

sculptors are more or less left to themselves. Of

course, the introduction of European methods

referred to above has somewhat altered this aspect.

As in painting, the idealistic has more or less

come into clash with the realistic. It was found

extremely difficult by Japanese painters of the

idealistic schools to adopt the best of the Occidental

method and still preserve the life of their creations,

namely, the beauty and the strength of their

brush work; so Japanese sculptors in wood, who of

the olden schools stand for idealism, have found it

extremely hard to maintain the glyptic character of

the Western school, yet retain the beauty and

strength of their chisel strokes. As with Japanese

painters, the problem for the sculptors lies in the

combination and harmonisation of the idealistic

Japanese Exhibition at Shepherd's Bush have

received from the general public, perhaps, the

highest praise next to that of embroidery, they do

not very much appeal to the Japanese. Because of

this demand in the West, regardless of its artistic

merit, we have an abundance of mediocre artists in

this line of work. It is maintained by many that a

numberof years must elapse before the ivory carvings

will find favour in Japan, and win an honoured

place as an ornament on a tokonoma, for as sup-

plied to the West they are by no means'expressive

of the saving characteristics of Japanese carving.

On the other hand, there are comparatively few

sculptors in wood in Japan, owing to the fact that

they have not yet found a market for their pro-

ductions outside of Japan, while the demand at

home is limited to very choice creations. One

will appreciate this fact more deeply when one

realises that in Japanese houses only on a tokonoma

—a special place slightly raised from the floor and

cut into the wall as an alcove—are art objects

placed, and generally one at a time. Take, for in-

stance, the wooden statue of Sugawara Muhizane, by

Yonehara, already referred to. In a Japanese home

WOOD PLAQUE WITH IVORY CARVING

BY SAITO KASUKE

Il8

CARVED AND LACQUERED SCREEN

this would most probably be placed on a tokonoma

in front of a scroll of a plum tree, as the statue

represents Michizane in boyhood composing a

poem on plum blossoms, on which occasion he

startled his teacher with his literary genius, and

these two objects would, no doubt, constitute the

whole of the decoration.

When we survey the progress of wood-carving in

Japan, we find that its path has been rather a

straight one. The course of its craftsmen has

been more easily marked out for them than for

those engaged in painting. This is chiefly because

there have not been many critics of the glyptic art,

as there are in the case of painting, who, being

often incompetent, only bewilder the artist until

he hardly knows which path to follow. The

sculptors are more or less left to themselves. Of

course, the introduction of European methods

referred to above has somewhat altered this aspect.

As in painting, the idealistic has more or less

come into clash with the realistic. It was found

extremely difficult by Japanese painters of the

idealistic schools to adopt the best of the Occidental

method and still preserve the life of their creations,

namely, the beauty and the strength of their

brush work; so Japanese sculptors in wood, who of

the olden schools stand for idealism, have found it

extremely hard to maintain the glyptic character of

the Western school, yet retain the beauty and

strength of their chisel strokes. As with Japanese

painters, the problem for the sculptors lies in the

combination and harmonisation of the idealistic