Constantin Gtiys

Nadar, was one of the dominant features of which astounds one at first by its absolute

his character, he was present at all the chief novelty. Assuredly neither Raphael nor Titian

engagements of the campaign, including Inker- nor Van Dyck ever thought of drawing in that

mann, Balaklava, and Sebastopol; and everywhere way; but the more one becomes familiar with

his artist's eye retained that which, when put on the medium the better one is enabled to under-

paper, resolved itself into the most striking and stand all the charm that lies in these nervous,

marvellous visions. Back in Paris the triumphal rapid drawings, which give so precise a sensation

return of the victorious troops provided him with of life; never dallying with futile details, but

fresh military scenes to record. He witnessed the aiming at producing a profound impression on the

most brilliant period of the Second Empire. Paris spectator.

was then the meeting-place of monarchs, sovereigns, Look at some of the water-colours from the

and princes, and every day there were reviews and Musee Carnavalet, in which he represents the

galas and races and fetes of all kinds, organised by women of his time; recall certain wash-drawings

a society caring for nought but enjoyment. All exhibited in M. Moline's gallery, and one must

this Guys had full opportunity of seeing and noting, realise that, despite apparent differences, this art,

and his drawings, his records, he scattered broad- in its profound and instinctive elegance, approaches

cast. Such was Guys' life up till the age of eighty that of our most graceful artists of the eighteenth

years. Then, in 1882, one carnival

night, he had both legs crushed

under the wheels of a cab. He

lived for seven years longer in the

Dubois Hospital, amid friends who

yearly grew more scarce; and Nadar

alone it was who followed his coffin

when the oldartist, who had stoically

borne the sufferings of his malady

and looked death calmly in the face,

at last expired, Such are the bare

details we possess as to Guys' life

and personality, and these are sup-

plemented on the one hand by

several photographs by Nadar, and

on the other by a portrait wherein

Manet represents him already old,

with white beard, and thinning hair

covering a broad brow, and scruti-

nising eyes of great vivacity.

For the rest, the biographical

information is completed by the

work itself. What his life was—

that life so full of movement and

adventure—what were his tastes in

fashion and otherwise, how ardent

his love of every form of life, how

clear his comprehension of an ideal

of beauty undreamt of hitherto by

artists—all this is told in his works

better than in the best of bio-

graphies.

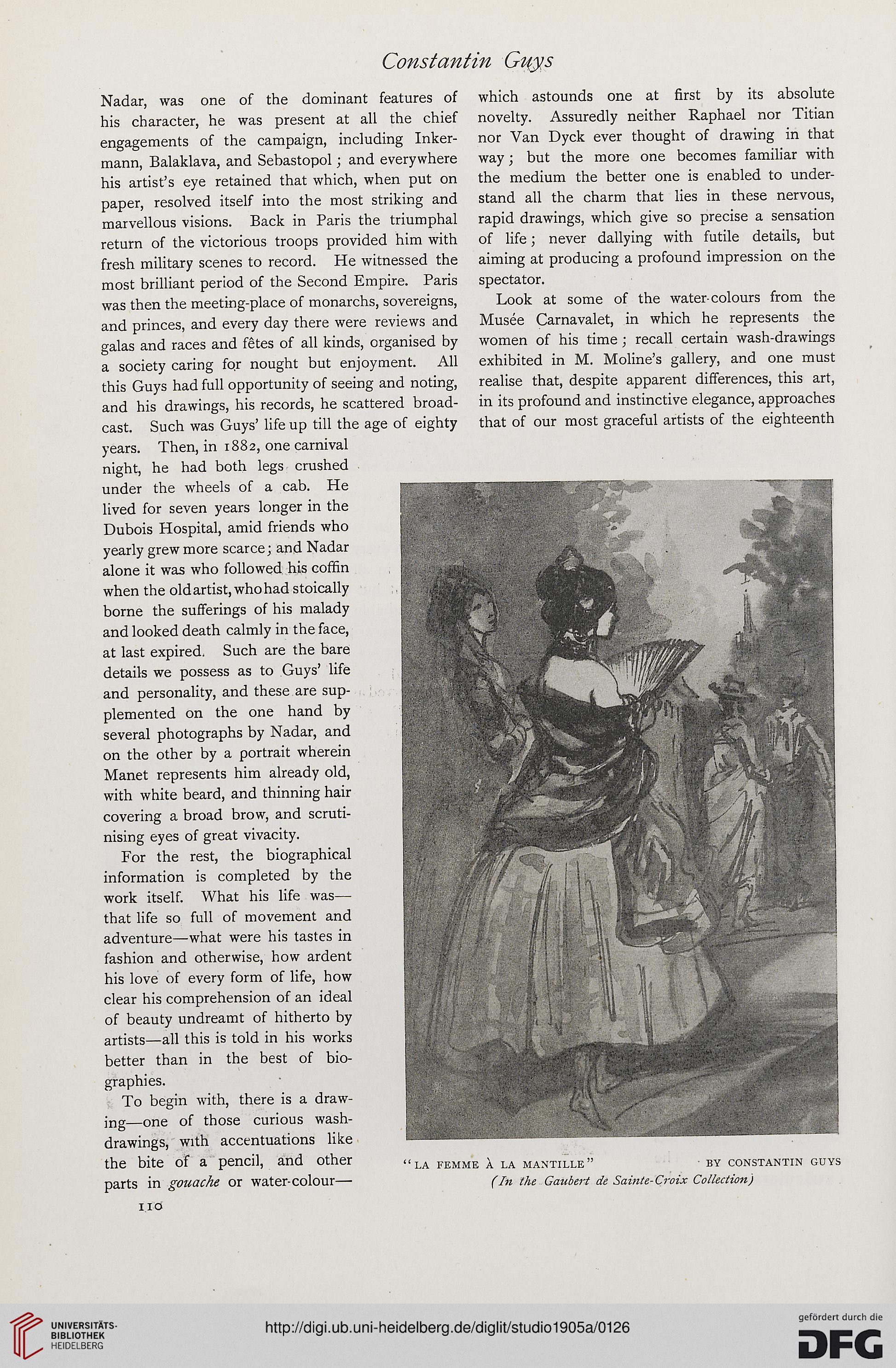

To begin with, there is a draw-

ing—one of those curious wash-

drawings, with accentuations like

the bite of a pencil, and other « la femme a la mantille" by constantin guys

parts in gouache or water-colour— (/„ the Gaubert de Sainte-Croix Collection)

Nadar, was one of the dominant features of which astounds one at first by its absolute

his character, he was present at all the chief novelty. Assuredly neither Raphael nor Titian

engagements of the campaign, including Inker- nor Van Dyck ever thought of drawing in that

mann, Balaklava, and Sebastopol; and everywhere way; but the more one becomes familiar with

his artist's eye retained that which, when put on the medium the better one is enabled to under-

paper, resolved itself into the most striking and stand all the charm that lies in these nervous,

marvellous visions. Back in Paris the triumphal rapid drawings, which give so precise a sensation

return of the victorious troops provided him with of life; never dallying with futile details, but

fresh military scenes to record. He witnessed the aiming at producing a profound impression on the

most brilliant period of the Second Empire. Paris spectator.

was then the meeting-place of monarchs, sovereigns, Look at some of the water-colours from the

and princes, and every day there were reviews and Musee Carnavalet, in which he represents the

galas and races and fetes of all kinds, organised by women of his time; recall certain wash-drawings

a society caring for nought but enjoyment. All exhibited in M. Moline's gallery, and one must

this Guys had full opportunity of seeing and noting, realise that, despite apparent differences, this art,

and his drawings, his records, he scattered broad- in its profound and instinctive elegance, approaches

cast. Such was Guys' life up till the age of eighty that of our most graceful artists of the eighteenth

years. Then, in 1882, one carnival

night, he had both legs crushed

under the wheels of a cab. He

lived for seven years longer in the

Dubois Hospital, amid friends who

yearly grew more scarce; and Nadar

alone it was who followed his coffin

when the oldartist, who had stoically

borne the sufferings of his malady

and looked death calmly in the face,

at last expired, Such are the bare

details we possess as to Guys' life

and personality, and these are sup-

plemented on the one hand by

several photographs by Nadar, and

on the other by a portrait wherein

Manet represents him already old,

with white beard, and thinning hair

covering a broad brow, and scruti-

nising eyes of great vivacity.

For the rest, the biographical

information is completed by the

work itself. What his life was—

that life so full of movement and

adventure—what were his tastes in

fashion and otherwise, how ardent

his love of every form of life, how

clear his comprehension of an ideal

of beauty undreamt of hitherto by

artists—all this is told in his works

better than in the best of bio-

graphies.

To begin with, there is a draw-

ing—one of those curious wash-

drawings, with accentuations like

the bite of a pencil, and other « la femme a la mantille" by constantin guys

parts in gouache or water-colour— (/„ the Gaubert de Sainte-Croix Collection)