Arthur Rackham

is merely a little more manual dexterity. Before his art. He cannot confine himself to the facts

he has reached middle age he has ceased to be an that are before him because plain actuality would

artist and has become only a manufacturer of never satisfy him and would never allow him the

stock patterns, who can turn out in any number scope for expression that he so intensely desires,

required things which are quite according to the But he has, all the same, to go through the drilling

samples he provided many years before. He stops of the realist or else he would be incapable of

short on the threshold of art and goes no further expanding in the directions where he can justify

because his blunted susceptibilities cannot perceive his artistic temperament most convincingly. If he

that there are any more worlds for him to conquer, had not the basis of sure knowledge he could

Possibly he is not unhappy, because, having no never construct those delightful perversions of

ideals he can have no disappointments and can nature which evidently give him such joy and show

never fall seriously short of what he intended : the rare richness of his imagination. For it must

but his happiness comes simply because he is too be remembered that his grotesques have to be

fossilised to experience any sensations. made credible, and with all their extravagance

With a worker of Mr. Rackham's type the case have to be so dramatically suggestive that they can

is very different. He could not remain a realist, for attract and hold the attention of the people whose

realism would destroy all the spirit and meaning of first inclination is to laugh at their absurdity.

Directly he began to fumble,

or to hint at any uncertainty in

his own mind, his power to per-

s"^' ■ suade would be gone ; he would

r i, seem to be attempting some-

V SL thing beyond his reach, or to

- ^| be deliberately poking fun at

J - his admirers. Such a breach

\ ^ "Vy °f f3-^ would be inexcusable ;

MMfe .oidtF^ ~* * lor *f hc's not ser'ous m his art'

> j^^^JJmy>*- ^T^iplk. no matter how amusing or

| '^^^jjjj^^^^^^^'*" on^y attitudinising to draw notice

^p|^-—■>> * ^T£py*lZ-~ ~* 'ess aPParetlt- The course of

* ' landscape painting which he

^jflBi^V* * j^^lfe^^^^ began in his boyhood, and has

jfl Wr^ kept UP 1:0 t^ie Present day, has

gjj BPIB nao- a most valuable influence

.. upon his art. It has guided

""- him into exquisite suggestion of

• k.^. nature's subtleties, into a true

appreciation of her sentiment

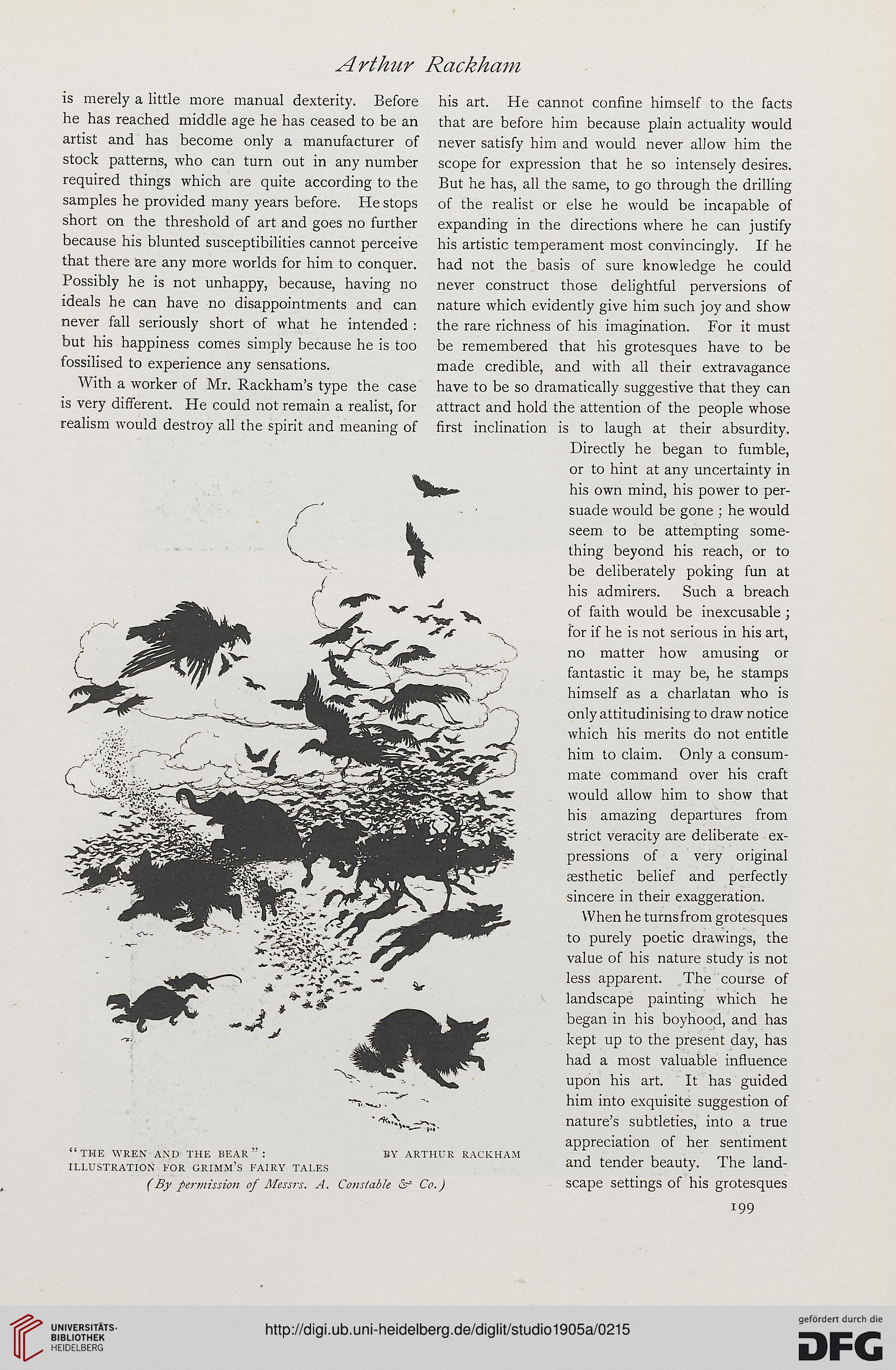

"THE WREN AND THE BEAR": BY ARTHUR RACKHAM , , , ry, , ,

ILLUSTRATION FOR GRIMM'S FAIRY TALES aIld tender DeaUtY- 1 lle lanC1

(By permission of Messrs. A. Constable <5? Co.) scape settings of his grotesques

199

is merely a little more manual dexterity. Before his art. He cannot confine himself to the facts

he has reached middle age he has ceased to be an that are before him because plain actuality would

artist and has become only a manufacturer of never satisfy him and would never allow him the

stock patterns, who can turn out in any number scope for expression that he so intensely desires,

required things which are quite according to the But he has, all the same, to go through the drilling

samples he provided many years before. He stops of the realist or else he would be incapable of

short on the threshold of art and goes no further expanding in the directions where he can justify

because his blunted susceptibilities cannot perceive his artistic temperament most convincingly. If he

that there are any more worlds for him to conquer, had not the basis of sure knowledge he could

Possibly he is not unhappy, because, having no never construct those delightful perversions of

ideals he can have no disappointments and can nature which evidently give him such joy and show

never fall seriously short of what he intended : the rare richness of his imagination. For it must

but his happiness comes simply because he is too be remembered that his grotesques have to be

fossilised to experience any sensations. made credible, and with all their extravagance

With a worker of Mr. Rackham's type the case have to be so dramatically suggestive that they can

is very different. He could not remain a realist, for attract and hold the attention of the people whose

realism would destroy all the spirit and meaning of first inclination is to laugh at their absurdity.

Directly he began to fumble,

or to hint at any uncertainty in

his own mind, his power to per-

s"^' ■ suade would be gone ; he would

r i, seem to be attempting some-

V SL thing beyond his reach, or to

- ^| be deliberately poking fun at

J - his admirers. Such a breach

\ ^ "Vy °f f3-^ would be inexcusable ;

MMfe .oidtF^ ~* * lor *f hc's not ser'ous m his art'

> j^^^JJmy>*- ^T^iplk. no matter how amusing or

| '^^^jjjj^^^^^^^'*" on^y attitudinising to draw notice

^p|^-—■>> * ^T£py*lZ-~ ~* 'ess aPParetlt- The course of

* ' landscape painting which he

^jflBi^V* * j^^lfe^^^^ began in his boyhood, and has

jfl Wr^ kept UP 1:0 t^ie Present day, has

gjj BPIB nao- a most valuable influence

.. upon his art. It has guided

""- him into exquisite suggestion of

• k.^. nature's subtleties, into a true

appreciation of her sentiment

"THE WREN AND THE BEAR": BY ARTHUR RACKHAM , , , ry, , ,

ILLUSTRATION FOR GRIMM'S FAIRY TALES aIld tender DeaUtY- 1 lle lanC1

(By permission of Messrs. A. Constable <5? Co.) scape settings of his grotesques

199