Paintings by Miss I. L. Gloag

indeed, through the very brilliance of its effect

upon the parts it strikes, it leaves in an obscurity

the more profound by comparison. Much among

the work of contemporary painters seems to par-

take of this character of selecting for a fierce

analysis some special aspect, a specialisation such

as has, to some extent, become inevitable in our

complex civilisation, and a consequent and con-

trasting neglect of the rest.

With all its robustness, with all its excellence of

painterlike and draughtsmanlike qualities, there is

something a little restless, a little tinge of dis-

satisfaction which occasionally betrays itself in

Miss Gloag’s work; as though she was admitting

that although she may have said in any particular

picture all that she meant to say, while she may

have expressed all that the momentary exigencies

permitted of being expressed, she knows and feels

that all is not there.

But we do not blame a war-correspondent

because he does not also happen to be a poet, and

we have no possible right or reason to censure a

painter for what he or she does not give us. Let

us try, whilst we enjoy, to appreciate to the full

what has been accomplished, so that our enjoy-

ment and our interest may be the more complete

and the more truly understanding.

In all the examples of Miss Gloag’s work here

illustrated, and indeed in all it has been the

writer’s lot to see from time to time in various of

the exhibitions, three cardinal traits are revealed—

sureness of drawing, directness of touch, and a

marked ability in the handling of paint. These

three characteristics, not by any means universally

encountered together in modern work, reveal the

artist as confident of herself, and it was the recog-

nition of these qualities that prompted the remark

made above as to the non-existence of a skeleton

in her artistic cupboard. This is indeed only what

one would expect to find in an artist whose studies

have comprised work at the Slade, at South Ken-

sington, and in Paris. Then, also, in many of her

pictures there is to be found an evidence of con-

noisseurship, of a delight in beautiful old things,

examples of furniture, rich brocades, fine carving,

marquetry, and rare craftsmanship of all kinds.

Fine workmanship surely appeals strongly here,

and in her own branch of art Miss Gloag evinces

a sound and able craftsmanship. Indeed, if we

have a bone to pick with her—and she would be

the first to be impatient of any writing about her art

that should only eulogise—it is that the fine way

in which she handles her paint transcends upon

occasion the merit of the subject per se. At the

34

same time, let us not ignore the fact, incontestable

in art, that it is most often the manner of treat-

ment—the quality of the draughtsmanship, the

fine play of contrasting light and colour—that

makes the subject; and whether it be some

exquisite vase or an old cracked teapot, a lovely

woman or a misshapen dwarf, matters not a whit,

provided that the genius of the artist has depicted

it with clear insight and a mastery of touch.

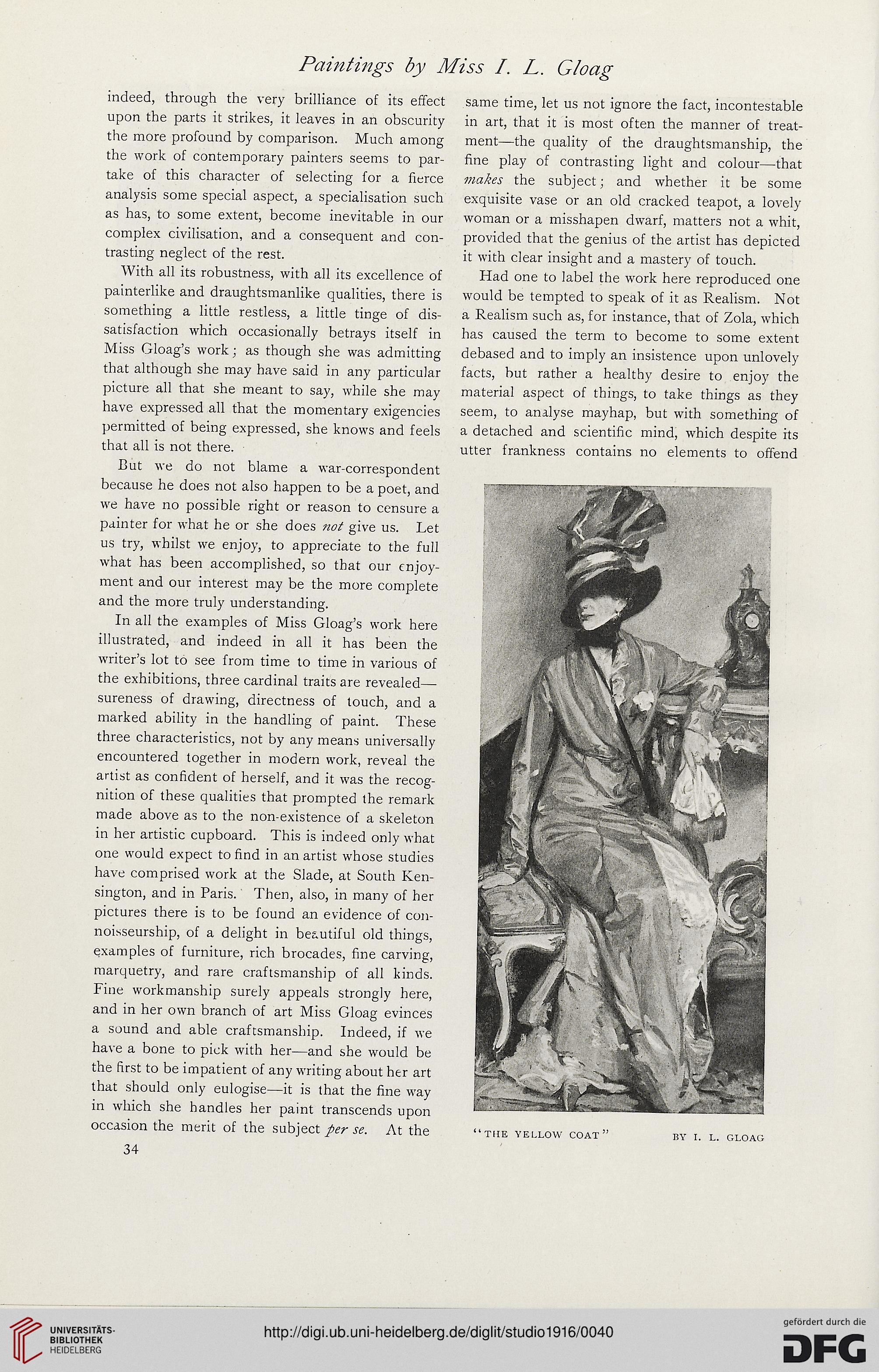

Had one to label the work here reproduced one

would be tempted to speak of it as Realism. Not

a Realism such as, for instance, that of Zola, which

has caused the term to become to some extent

debased and to imply an insistence upon unlovely

facts, but rather a healthy desire to enjoy the

material aspect of things, to take things as they

seem, to analyse mayhap, but with something of

a detached and scientific mind, which despite its

utter frankness contains no elements to offend

“the yellow coat’

BY' I. L. GLOAG

indeed, through the very brilliance of its effect

upon the parts it strikes, it leaves in an obscurity

the more profound by comparison. Much among

the work of contemporary painters seems to par-

take of this character of selecting for a fierce

analysis some special aspect, a specialisation such

as has, to some extent, become inevitable in our

complex civilisation, and a consequent and con-

trasting neglect of the rest.

With all its robustness, with all its excellence of

painterlike and draughtsmanlike qualities, there is

something a little restless, a little tinge of dis-

satisfaction which occasionally betrays itself in

Miss Gloag’s work; as though she was admitting

that although she may have said in any particular

picture all that she meant to say, while she may

have expressed all that the momentary exigencies

permitted of being expressed, she knows and feels

that all is not there.

But we do not blame a war-correspondent

because he does not also happen to be a poet, and

we have no possible right or reason to censure a

painter for what he or she does not give us. Let

us try, whilst we enjoy, to appreciate to the full

what has been accomplished, so that our enjoy-

ment and our interest may be the more complete

and the more truly understanding.

In all the examples of Miss Gloag’s work here

illustrated, and indeed in all it has been the

writer’s lot to see from time to time in various of

the exhibitions, three cardinal traits are revealed—

sureness of drawing, directness of touch, and a

marked ability in the handling of paint. These

three characteristics, not by any means universally

encountered together in modern work, reveal the

artist as confident of herself, and it was the recog-

nition of these qualities that prompted the remark

made above as to the non-existence of a skeleton

in her artistic cupboard. This is indeed only what

one would expect to find in an artist whose studies

have comprised work at the Slade, at South Ken-

sington, and in Paris. Then, also, in many of her

pictures there is to be found an evidence of con-

noisseurship, of a delight in beautiful old things,

examples of furniture, rich brocades, fine carving,

marquetry, and rare craftsmanship of all kinds.

Fine workmanship surely appeals strongly here,

and in her own branch of art Miss Gloag evinces

a sound and able craftsmanship. Indeed, if we

have a bone to pick with her—and she would be

the first to be impatient of any writing about her art

that should only eulogise—it is that the fine way

in which she handles her paint transcends upon

occasion the merit of the subject per se. At the

34

same time, let us not ignore the fact, incontestable

in art, that it is most often the manner of treat-

ment—the quality of the draughtsmanship, the

fine play of contrasting light and colour—that

makes the subject; and whether it be some

exquisite vase or an old cracked teapot, a lovely

woman or a misshapen dwarf, matters not a whit,

provided that the genius of the artist has depicted

it with clear insight and a mastery of touch.

Had one to label the work here reproduced one

would be tempted to speak of it as Realism. Not

a Realism such as, for instance, that of Zola, which

has caused the term to become to some extent

debased and to imply an insistence upon unlovely

facts, but rather a healthy desire to enjoy the

material aspect of things, to take things as they

seem, to analyse mayhap, but with something of

a detached and scientific mind, which despite its

utter frankness contains no elements to offend

“the yellow coat’

BY' I. L. GLOAG