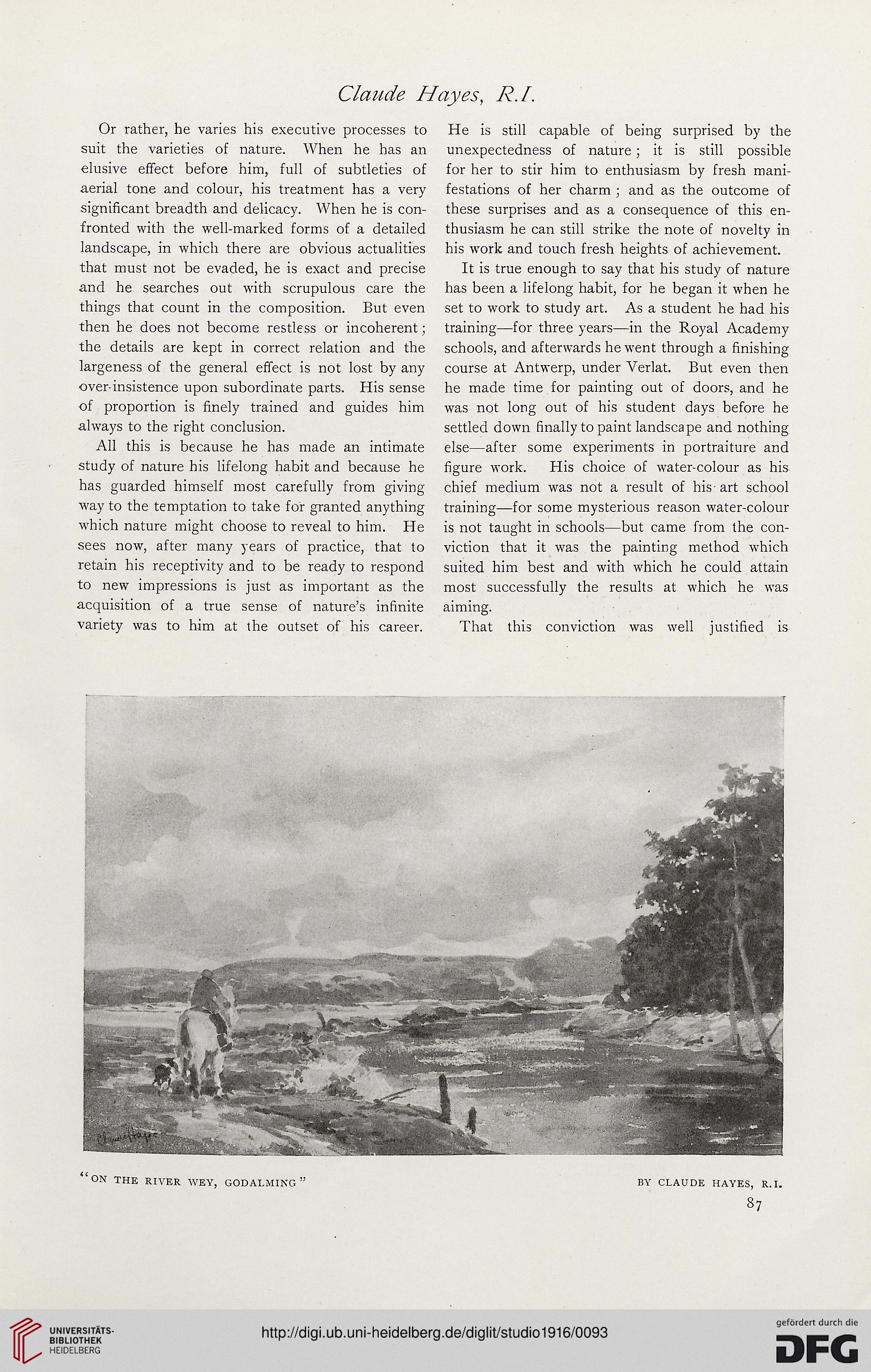

Claude Hayes, R.l.

Or rather, he varies his executive processes to

suit the varieties of nature. When he has an

elusive effect before him, full of subtleties of

aerial tone and colour, his treatment has a very

significant breadth and delicacy. When he is con-

fronted with the well-marked forms of a detailed

landscape, in which there are obvious actualities

that must not be evaded, he is exact and precise

and he searches out with scrupulous care the

things that count in the composition. But even

then he does not become restless or incoherent;

the details are kept in correct relation and the

largeness of the general effect is not lost by any

over-insistence upon subordinate parts. His sense

of proportion is finely trained and guides him

always to the right conclusion.

All this is because he has made an intimate

study of nature his lifelong habit and because he

has guarded himself most carefully from giving

■way to the temptation to take for granted anything

which nature might choose to reveal to him. He

sees now, after many years of practice, that to

retain his receptivity and to be ready to respond

to new impressions is just as important as the

acquisition of a true sense of nature’s infinite

variety was to him at the outset of his career.

He is still capable of being surprised by the

unexpectedness of nature; it is still possible

for her to stir him to enthusiasm by fresh mani-

festations of her charm ; and as the outcome of

these surprises and as a consequence of this en-

thusiasm he can still strike the note of novelty in

his work and touch fresh heights of achievement.

It is true enough to say that his study of nature

has been a lifelong habit, for he began it when he

set to work to study art. As a student he had his

training—for three years—in the Royal Academy

schools, and afterwards he went through a finishing

course at Antwerp, under Verlat. But even then

he made time for painting out of doors, and he

was not long out of his student days before he

settled down finally to paint landscape and nothing

else—after some experiments in portraiture and

figure work. His choice of water-colour as his

chief medium was not a result of his art school

training—for some mysterious reason water-colour

is not taught in schools—but came from the con-

viction that it was the painting method which

suited him best and with which he could attain

most successfully the results at which he was

aiming.

That this conviction was well justified is

Or rather, he varies his executive processes to

suit the varieties of nature. When he has an

elusive effect before him, full of subtleties of

aerial tone and colour, his treatment has a very

significant breadth and delicacy. When he is con-

fronted with the well-marked forms of a detailed

landscape, in which there are obvious actualities

that must not be evaded, he is exact and precise

and he searches out with scrupulous care the

things that count in the composition. But even

then he does not become restless or incoherent;

the details are kept in correct relation and the

largeness of the general effect is not lost by any

over-insistence upon subordinate parts. His sense

of proportion is finely trained and guides him

always to the right conclusion.

All this is because he has made an intimate

study of nature his lifelong habit and because he

has guarded himself most carefully from giving

■way to the temptation to take for granted anything

which nature might choose to reveal to him. He

sees now, after many years of practice, that to

retain his receptivity and to be ready to respond

to new impressions is just as important as the

acquisition of a true sense of nature’s infinite

variety was to him at the outset of his career.

He is still capable of being surprised by the

unexpectedness of nature; it is still possible

for her to stir him to enthusiasm by fresh mani-

festations of her charm ; and as the outcome of

these surprises and as a consequence of this en-

thusiasm he can still strike the note of novelty in

his work and touch fresh heights of achievement.

It is true enough to say that his study of nature

has been a lifelong habit, for he began it when he

set to work to study art. As a student he had his

training—for three years—in the Royal Academy

schools, and afterwards he went through a finishing

course at Antwerp, under Verlat. But even then

he made time for painting out of doors, and he

was not long out of his student days before he

settled down finally to paint landscape and nothing

else—after some experiments in portraiture and

figure work. His choice of water-colour as his

chief medium was not a result of his art school

training—for some mysterious reason water-colour

is not taught in schools—but came from the con-

viction that it was the painting method which

suited him best and with which he could attain

most successfully the results at which he was

aiming.

That this conviction was well justified is