Modern Swiss School of Alpine Landscape Art

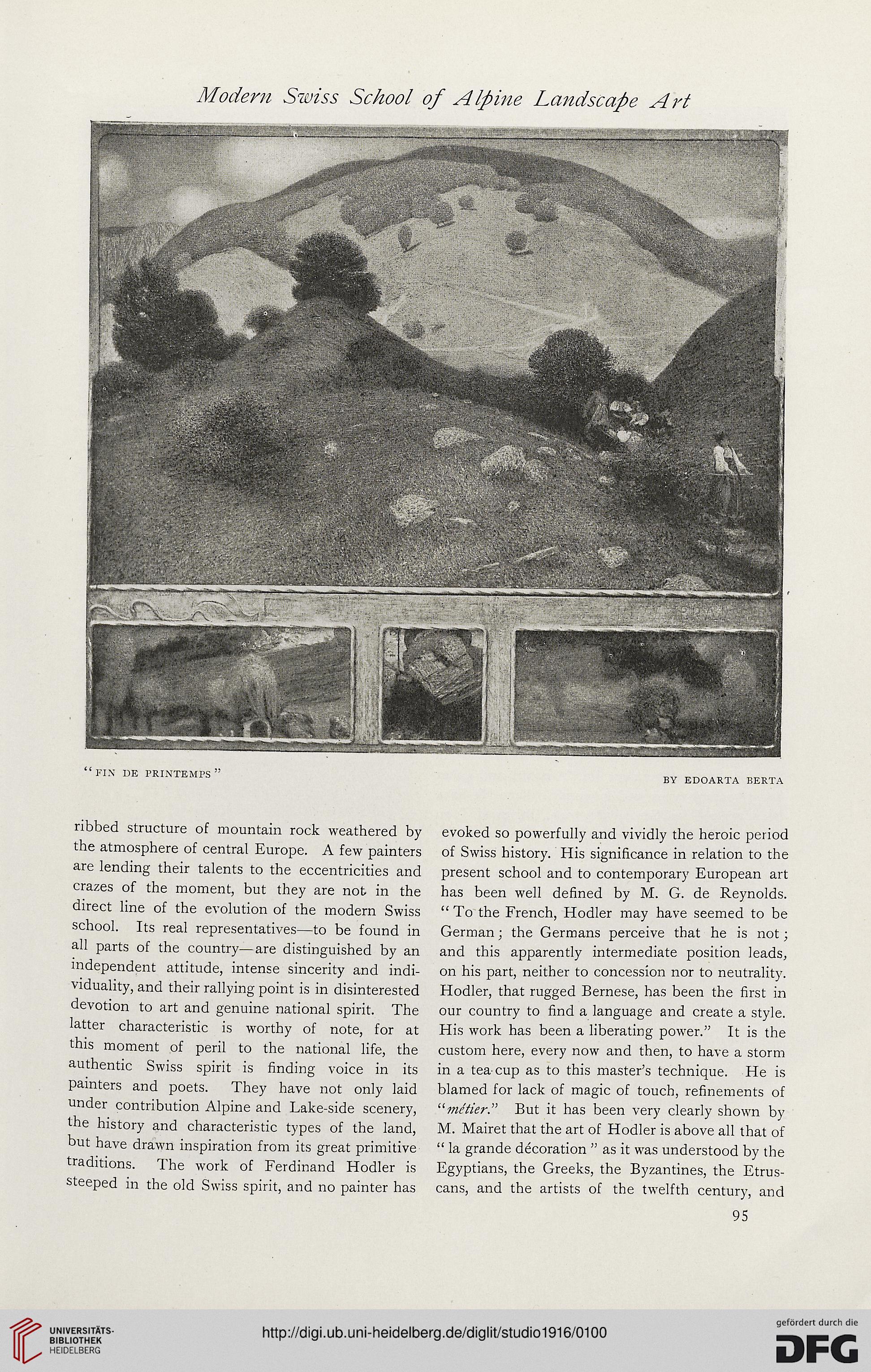

“fin de printemps

BY EDOARTA BERTA

ribbed structure of mountain rock weathered by

the atmosphere of central Europe. A few painters

are lending their talents to the eccentricities and

crazes of the moment, but they are not in the

direct line of the evolution of the modern Swiss

school. Its real representatives—to be found in

all parts of the country—are distinguished by an

independent attitude, intense sincerity and indi-

viduality, and their rallying point is in disinterested

devotion to art and genuine national spirit. The

latter characteristic is worthy of note, for at

this moment of peril to the national life, the

authentic Swiss spirit is finding voice in its

painters and poets. They have not only laid

under contribution Alpine and Lake-side scenery,

the history and characteristic types of the land,

but have drawn inspiration from its great primitive

traditions. The work of Ferdinand Hodler is

steeped in the old Swiss spirit, and no painter has

evoked so powerfully and vividly the heroic period

of Swiss history. His significance in relation to the

present school and to contemporary European art

has been well defined by M. G. de Reynolds.

“ To the French, Hodler may have seemed to be

German; the Germans perceive that he is not;

and this apparently intermediate position leads,

on his part, neither to concession nor to neutrality.

Hodler, that rugged Bernese, has been the first in

our country to find a language and create a style.

His work has been a liberating power.” It is the

custom here, every now and then, to have a storm

in a tea cup as to this master’s technique. He is

blamed for lack of magic of touch, refinements of

“metier.” But it has been very clearly shown by

M. Mairet that the art of Hodler is above all that of

“ la grande decoration ” as it was understood by the

Egyptians, the Greeks, the Byzantines, the Etrus-

cans, and the artists of the twelfth century, and

95

“fin de printemps

BY EDOARTA BERTA

ribbed structure of mountain rock weathered by

the atmosphere of central Europe. A few painters

are lending their talents to the eccentricities and

crazes of the moment, but they are not in the

direct line of the evolution of the modern Swiss

school. Its real representatives—to be found in

all parts of the country—are distinguished by an

independent attitude, intense sincerity and indi-

viduality, and their rallying point is in disinterested

devotion to art and genuine national spirit. The

latter characteristic is worthy of note, for at

this moment of peril to the national life, the

authentic Swiss spirit is finding voice in its

painters and poets. They have not only laid

under contribution Alpine and Lake-side scenery,

the history and characteristic types of the land,

but have drawn inspiration from its great primitive

traditions. The work of Ferdinand Hodler is

steeped in the old Swiss spirit, and no painter has

evoked so powerfully and vividly the heroic period

of Swiss history. His significance in relation to the

present school and to contemporary European art

has been well defined by M. G. de Reynolds.

“ To the French, Hodler may have seemed to be

German; the Germans perceive that he is not;

and this apparently intermediate position leads,

on his part, neither to concession nor to neutrality.

Hodler, that rugged Bernese, has been the first in

our country to find a language and create a style.

His work has been a liberating power.” It is the

custom here, every now and then, to have a storm

in a tea cup as to this master’s technique. He is

blamed for lack of magic of touch, refinements of

“metier.” But it has been very clearly shown by

M. Mairet that the art of Hodler is above all that of

“ la grande decoration ” as it was understood by the

Egyptians, the Greeks, the Byzantines, the Etrus-

cans, and the artists of the twelfth century, and

95