Water-Colours by E. M. Synge

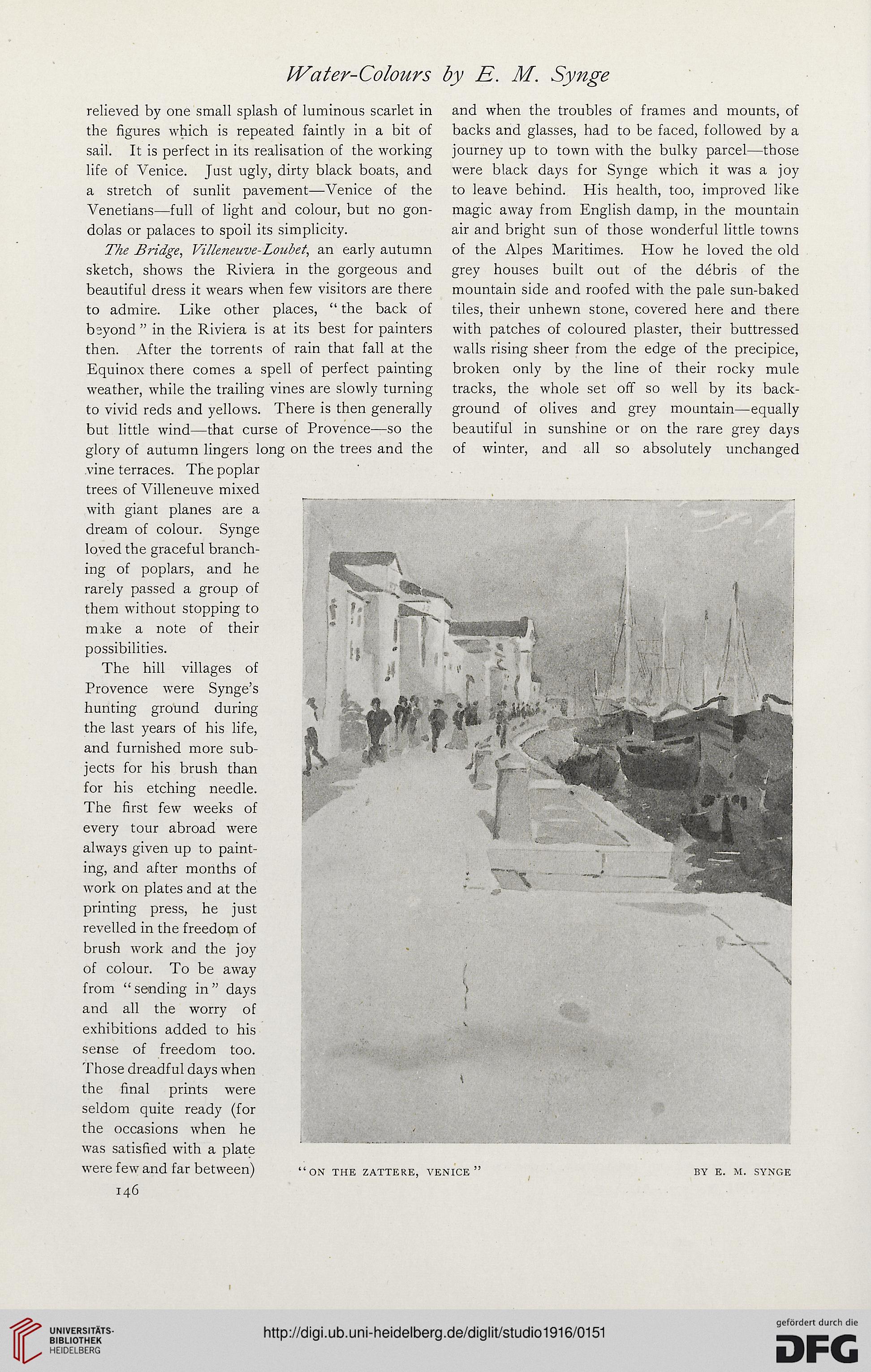

relieved by one small splash of luminous scarlet in

the figures which is repeated faintly in a bit of

sail. It is perfect in its realisation of the working

life of Venice. Just ugly, dirty black boats, and

a stretch of sunlit pavement—Venice of the

Venetians—full of light and colour, but no gon-

dolas or palaces to spoil its simplicity.

The Bridge, Villeneuve-Loubet, an early autumn

sketch, shows the Riviera in the gorgeous and

beautiful dress it wears when few visitors are there

to admire. Like other places, “ the back of

beyond ” in the Riviera is at its best for painters

then. After the torrents of rain that fall at the

Equinox there comes a spell of perfect painting

weather, while the trailing vines are slowly turning

to vivid reds and yellows. There is then generally

but little wind—that curse of Provence—so the

glory of autumn lingers long on the trees and the

vine terraces. The poplar

trees of Villeneuve mixed

with giant planes are a

dream of colour. Synge

loved the graceful branch-

ing of poplars, and he

rarely passed a group of

them without stopping to

make a note of their

possibilities.

The hill villages of

Provence were Synge’s

hunting ground during

the last years of his life,

and furnished more sub-

jects for his brush than

for his etching needle.

The first few weeks of

every tour abroad were

always given up to paint-

ing, and after months of

work on plates and at the

printing press, he just

revelled in the freedom of

brush work and the joy

of colour. To be away

from “ sending in ” days

and all the worry of

exhibitions added to his

sense of freedom too.

Those dreadful days when

the final prints were

seldom quite ready (for

the occasions when he

was satisfied with a plate

were few and far between)

146

and when the troubles of frames and mounts, of

backs and glasses, had to be faced, followed by a

journey up to town with the bulky parcel—those

were black days for Synge which it was a joy

to leave behind. His health, too, improved like

magic away from English damp, in the mountain

air and bright sun of those wonderful little towns

of the Alpes Maritimes. How he loved the old

grey houses built out of the debris of the

mountain side and roofed with the pale sun-baked

tiles, their unhewn stone, covered here and there

with patches of coloured plaster, their buttressed

walls rising sheer from the edge of the precipice,

broken only by the line of their rocky mule

tracks, the whole set off so well by its back-

ground of olives and grey mountain—equally

beautiful in sunshine or on the rare grey days

of winter, and all so absolutely unchanged

BY E. M. SYNGE

relieved by one small splash of luminous scarlet in

the figures which is repeated faintly in a bit of

sail. It is perfect in its realisation of the working

life of Venice. Just ugly, dirty black boats, and

a stretch of sunlit pavement—Venice of the

Venetians—full of light and colour, but no gon-

dolas or palaces to spoil its simplicity.

The Bridge, Villeneuve-Loubet, an early autumn

sketch, shows the Riviera in the gorgeous and

beautiful dress it wears when few visitors are there

to admire. Like other places, “ the back of

beyond ” in the Riviera is at its best for painters

then. After the torrents of rain that fall at the

Equinox there comes a spell of perfect painting

weather, while the trailing vines are slowly turning

to vivid reds and yellows. There is then generally

but little wind—that curse of Provence—so the

glory of autumn lingers long on the trees and the

vine terraces. The poplar

trees of Villeneuve mixed

with giant planes are a

dream of colour. Synge

loved the graceful branch-

ing of poplars, and he

rarely passed a group of

them without stopping to

make a note of their

possibilities.

The hill villages of

Provence were Synge’s

hunting ground during

the last years of his life,

and furnished more sub-

jects for his brush than

for his etching needle.

The first few weeks of

every tour abroad were

always given up to paint-

ing, and after months of

work on plates and at the

printing press, he just

revelled in the freedom of

brush work and the joy

of colour. To be away

from “ sending in ” days

and all the worry of

exhibitions added to his

sense of freedom too.

Those dreadful days when

the final prints were

seldom quite ready (for

the occasions when he

was satisfied with a plate

were few and far between)

146

and when the troubles of frames and mounts, of

backs and glasses, had to be faced, followed by a

journey up to town with the bulky parcel—those

were black days for Synge which it was a joy

to leave behind. His health, too, improved like

magic away from English damp, in the mountain

air and bright sun of those wonderful little towns

of the Alpes Maritimes. How he loved the old

grey houses built out of the debris of the

mountain side and roofed with the pale sun-baked

tiles, their unhewn stone, covered here and there

with patches of coloured plaster, their buttressed

walls rising sheer from the edge of the precipice,

broken only by the line of their rocky mule

tracks, the whole set off so well by its back-

ground of olives and grey mountain—equally

beautiful in sunshine or on the rare grey days

of winter, and all so absolutely unchanged

BY E. M. SYNGE