July 26, 1890.] punch, oe the london chaeivarl 37

MODERN TYPES.

{By Mr, Punch's own Type Writer.)

No. XYI.—THE HURLINGHAM GIRL.

It is not so easy as it might appear to define the Hurlingham Girl

with complete accuracy. To say of her that she is one whose spirits

are higher than her aspirations, would be true but inadequate. For,

at the best, aspirations are etherial things, and those of the Hurling-

ham Girl, if they ever existed, have been so recklessly puffed into

space as to vanish almost entirely from view. In any case they

afford a very unsubstantial basis of comparison to the student who

seeks to infer from them her general character. Yet it would be

wrong to assume that she has dispensed with the etherial on account

of her devotion to what is solid. Indeed nothing is more certain

about her than the contempt with which she has been willingly

taught to look upon all the attainments that are usually dignified

with this epithet. History and geography, classics and mathematics,

modern languages (her own and those of foreign nations), all these

she candidly despises. Let others make their nests upon the shady

branches of the tree of learning. For herself she is fain to soar into

the empyrean of society, and to gaze with undazzled eyes into the

sun of the smart set. She has of course had the advantage of

teachers of all sorts, but the claims made upon her time by thought-

less parents have usually been so great as to leave her at the end of

her school-room period with a few

brittle fragments of knowledge, which , x "s sufficient mental pabulum for a grown-

Bhift and change in her mind as the t/V f^i~ I x~r^~\ UP woman.

bits of glass might shift in a kaleido- C^^-IJl *s tumeoeBsary to describe further

scope from which the looking-glass /—n ,„ \ wSUPb^» W%"*f ty>&,<jk'l, jj the pursuits and occupations of the

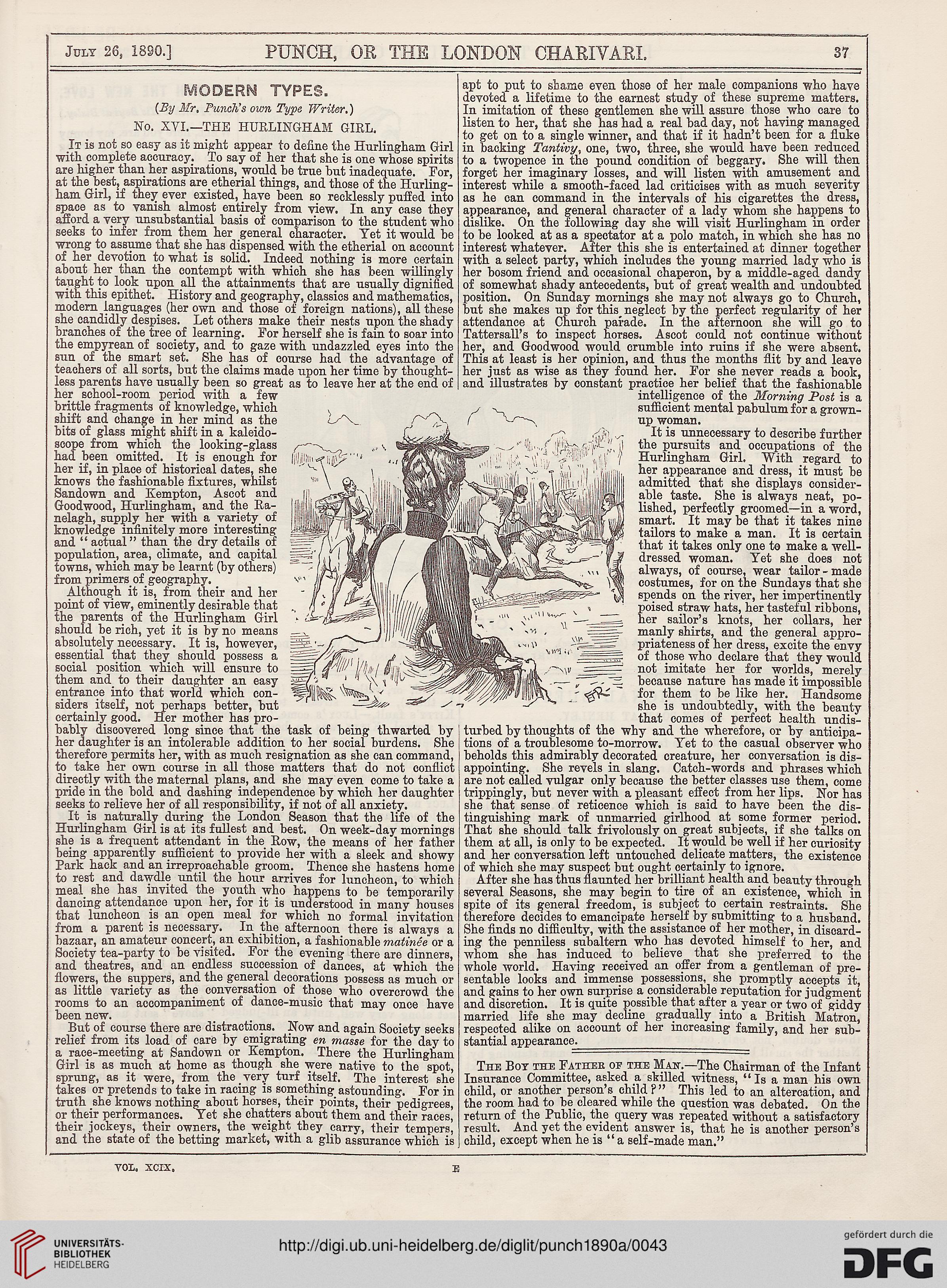

had been omitted. It is enough for ftjkurM??"'' ...TPaKTaWy**..! •• .'.*->^VV!fSi*'' '*',( ? Hurlingham Girl. "With regard to

her if, in place of historical dates, she ''v\'" i MOriSwH ** C' t L) "\\ ■' Liia. her appearance and dress, it must be

knows the fashionable fixtures, whilst \ Qi Ui» ' HwMp«^lilL!jj admitted that she displays consider-

Sandown and Kempton, Ascot and Jl. rf*^j*V P l''J I1i<HIb8B^' 'f^M^^S»^y \1 -K .tt^^ ; -' /NilJJ a^e taste. She is always neat, po-

Goodwood, Hurlingham, and the Ra- | •^teJjVAV, i |||. 1 - ,,, V 1 K/ "\ lished, perfectly groomed—in a word,

nelagh, supply, her with a variety, of ,hM^^\MA WKmb<mm3S^mm smart. It may be that it takes nine

knowledge infinitely more interesting IjM / \ fW^WK^SL Wm^^^mM tailors to make a man. It is certain

and " actual" than the dry details of fyfw lot / jflfflK^Pwi W^W^j that it takes only one to make a well-

population, area, climate, and capital is=z{t\ ' m§iW / JSSlIliS'i^T'X^ &e__<=^\3 dressed, woman. Yet she does not

towns, which may be learnt (by others) : W JB / .flPWllififi^b^ "< Ǥ. always, of course, wear tailor - made

from primers of geography. vlil P/^ \\\t / lIllH ^T^-^^*^ «8 costumes, for on the Sundays that she

Although it is, from their and her - f JJ 4.Mijj,,/ ■■.rtV^^^*" M spends on the river, her impertinently

point of view, eminently desirable that ., /( ' ft ^ =Mj\\\\ ///////^^^^^^^"^. s » poised straw hats, her tasteful ribbons,

the parents of the Hurlingham Girl ' //^^^M'^ -'''' —-==== ner sailor's knots, her collars, her

should be rich, yet it is by no means ^ JW * "M ' \ ^rrSr manly shirts, and the general appro-

absolutely necessary. It is, however, ^--- ~-^QkJHHH^^ .-»v> .... priatenessof her dress, excite the envy

essential that they should possess a ^===/y^T'; / ^M^^^^M^M/^^-^, "*"' - —: °f those who declare that they would

social position which will ensure to =^ a'"'' / ft\ 'J^^^^^^^B^r il - - ' not imitate her for worlds, merely

them and to their daughter an easy ' * S\ i r ^^^^K^MmSi--— 7~^-~%. because nature has made it impossible

entrance into that world which con- ^SJfe v»^v' " ' <%&~ ~ f°r them to be like her. Handsome

siders itself, not perhaps better, but ■—-» / she is undoubtedly, with the beauty

certainly good. Her mother has pro- that comes of perfect health undis,

apt to put to shame even those of her male companions who have

devoted a lifetime to the earnest study of these supreme matters.

In imitation of these gentlemen she will assure those who care to

listen to her, that she has had a real bad day, not having managed

to get on to a single winner, and that if it hadn't been for a fluke

in backing Tantivy, one, two, three, she would have been reduced

to a twopence in the pound condition of beggary. She will then

forget her imaginary losses, and will listen with amusement and

interest while a smooth-faced lad criticises with as much severity

as he can command in the intervals of his cigarettes the dress,

appearance, and general character of a lady whom she happens to

dislike. On the following day she will visit Hurlingham in order

to be looked at as a spectator at a polo match, in which she has no

interest whatever. After this she is entertained at dinner together

with a select party, which includes the young married lady who is

her bosom friend and occasional chaperon, by a middle-aged dandy

of somewhat shady antecedents, but of great wealth and undoubted

position. On Sunday mornings she may not always go to Church,

but she makes up for this_ neglect by the perfect regularity of her

attendance at Church parade. In the afternoon she will go to

Tattersall's to inspect horses. Ascot could not continue without

her, and Goodwood would crumble into ruins if she were absent.

This at least is her opinion, and thus the months flit by and leave

her just as wise as they found her. For she never reads a book,

and illustrates by constant practice her belief that the fashionable

intelligence of the Morning Post is a

bably discovered long since that the task of being thwarted by

her daughter is an intolerable addition to her social burdens. She

therefore permits her, with as much resignation as she can command,

to take her own course in all those matters that do not conflict

directly with the maternal plans, and she may even come to take a

pride in the bold and dashing independence by which her daughter

seeks to relieve her of all responsibility, if not of all anxiety.

It is naturally during the London Season that the life of the

Hurlingham Girl is at its fullest and best. On week-day mornings

she is a frequent attendant in the Row, the means of her father

being apparently sufficient to provide her with a sleek and showy

Park hack and an irreproachable groom. Thence she hastens home

to rest and dawdle until the hour arrives for luncheon, to which

meal she has invited the youth who happens to be temporarily

dancing attendance upon her, for it is understood in many houses

that luncheon is an open meal for which no formal invitation

from a parent is necessary. In the_ afternoon there is always a

bazaar, an amateur concert, an exhibition, a fashionable matinee or a

Society tea-party to be visited. For the evening there are dinners,

and. theatres, and an endless succession of_ dances, at which the

flowers, the suppers, and the general decorations possess as much or

as little variety as the conversation of those who overcrowd the

rooms to an accompaniment of dance-music that may once have

been new.

But of course there are distractions. Now and again Society seeks

relief from its load of care by emigrating en masse for the day to

a race-meeting at Sandown or Kempton. There the Hurlingham

Girl is as much at home as though she were native to the spot,

sprung, as it were, from the very turf itself. The interest she

takes or pretends to take in racing is something astounding. For in

truth she knows nothing about horses, their points, their pedigrees,

or their performances. Yet she chatters about them and their races,

their jockeys, their owners, the weight they carry, their tempers,

and the state of the betting market, with a glib assurance which is

turbed by thoughts of the why and the wherefore, or by anticipa-

tions of a troublesome to-morrow. Yet to the casual observer who

beholds this admirably decorated creature, her conversation is dis-

appointing. She revels in slang. Catch-words and phrases which

are not called vulgar only because the better classes use them, come

trippingly, but never with a pleasant effect from her lips. Nor has

she that sense of reticence which is said to have been the dis-

tinguishing mark of unmarried girlhood at some former period.

That she should talk frivolously on great subjects, if she talks on

them at all, is only to be expected. It would be well if her curiosity

and her conversation left untouched delicate matters, the existence

of which Bhe may suspect but ought certainly to ignore.

After she has thus flaunted her brilliant health and beauty through

several Seasons, she may begin to tire of an existence, which in

spite of its general freedom, is subject to certain restraints. She

therefore decides to emancipate herself by submitting to a husband.

She finds no difficulty, with the assistance of her mother, in discard-

ing the penniless subaltern who has devoted himself to her, and

whom she has induced to believe that she preferred to the

whole world. Having received an offer from a gentleman of pre-

sentable looks and immense possessions, she promptly accepts it,

and gains to her own surprise a considerable reputation for judgment

and. discretion. It is quite possible that after a year or two of giddy

married life she may decline gradually^ into a British Matron,

respected alike on account of her increasing family, and her sub-

stantial appearance_._

The Box the Fateee of the Mak.—The Chairman of the Infant

Insurance Committee, asked a skilled witness, "Is a man his own

child, or another person's child?" This led to an altercation, and

the room had to be cleared while the question was debated. On the

return of the Public, the query was repeated without a satisfactory

result. And yet the evident answer is, that he is another person's

child, except when he is "a self-made man."

vol,, xcrx.

E

MODERN TYPES.

{By Mr, Punch's own Type Writer.)

No. XYI.—THE HURLINGHAM GIRL.

It is not so easy as it might appear to define the Hurlingham Girl

with complete accuracy. To say of her that she is one whose spirits

are higher than her aspirations, would be true but inadequate. For,

at the best, aspirations are etherial things, and those of the Hurling-

ham Girl, if they ever existed, have been so recklessly puffed into

space as to vanish almost entirely from view. In any case they

afford a very unsubstantial basis of comparison to the student who

seeks to infer from them her general character. Yet it would be

wrong to assume that she has dispensed with the etherial on account

of her devotion to what is solid. Indeed nothing is more certain

about her than the contempt with which she has been willingly

taught to look upon all the attainments that are usually dignified

with this epithet. History and geography, classics and mathematics,

modern languages (her own and those of foreign nations), all these

she candidly despises. Let others make their nests upon the shady

branches of the tree of learning. For herself she is fain to soar into

the empyrean of society, and to gaze with undazzled eyes into the

sun of the smart set. She has of course had the advantage of

teachers of all sorts, but the claims made upon her time by thought-

less parents have usually been so great as to leave her at the end of

her school-room period with a few

brittle fragments of knowledge, which , x "s sufficient mental pabulum for a grown-

Bhift and change in her mind as the t/V f^i~ I x~r^~\ UP woman.

bits of glass might shift in a kaleido- C^^-IJl *s tumeoeBsary to describe further

scope from which the looking-glass /—n ,„ \ wSUPb^» W%"*f ty>&,<jk'l, jj the pursuits and occupations of the

had been omitted. It is enough for ftjkurM??"'' ...TPaKTaWy**..! •• .'.*->^VV!fSi*'' '*',( ? Hurlingham Girl. "With regard to

her if, in place of historical dates, she ''v\'" i MOriSwH ** C' t L) "\\ ■' Liia. her appearance and dress, it must be

knows the fashionable fixtures, whilst \ Qi Ui» ' HwMp«^lilL!jj admitted that she displays consider-

Sandown and Kempton, Ascot and Jl. rf*^j*V P l''J I1i<HIb8B^' 'f^M^^S»^y \1 -K .tt^^ ; -' /NilJJ a^e taste. She is always neat, po-

Goodwood, Hurlingham, and the Ra- | •^teJjVAV, i |||. 1 - ,,, V 1 K/ "\ lished, perfectly groomed—in a word,

nelagh, supply, her with a variety, of ,hM^^\MA WKmb<mm3S^mm smart. It may be that it takes nine

knowledge infinitely more interesting IjM / \ fW^WK^SL Wm^^^mM tailors to make a man. It is certain

and " actual" than the dry details of fyfw lot / jflfflK^Pwi W^W^j that it takes only one to make a well-

population, area, climate, and capital is=z{t\ ' m§iW / JSSlIliS'i^T'X^ &e__<=^\3 dressed, woman. Yet she does not

towns, which may be learnt (by others) : W JB / .flPWllififi^b^ "< Ǥ. always, of course, wear tailor - made

from primers of geography. vlil P/^ \\\t / lIllH ^T^-^^*^ «8 costumes, for on the Sundays that she

Although it is, from their and her - f JJ 4.Mijj,,/ ■■.rtV^^^*" M spends on the river, her impertinently

point of view, eminently desirable that ., /( ' ft ^ =Mj\\\\ ///////^^^^^^^"^. s » poised straw hats, her tasteful ribbons,

the parents of the Hurlingham Girl ' //^^^M'^ -'''' —-==== ner sailor's knots, her collars, her

should be rich, yet it is by no means ^ JW * "M ' \ ^rrSr manly shirts, and the general appro-

absolutely necessary. It is, however, ^--- ~-^QkJHHH^^ .-»v> .... priatenessof her dress, excite the envy

essential that they should possess a ^===/y^T'; / ^M^^^^M^M/^^-^, "*"' - —: °f those who declare that they would

social position which will ensure to =^ a'"'' / ft\ 'J^^^^^^^B^r il - - ' not imitate her for worlds, merely

them and to their daughter an easy ' * S\ i r ^^^^K^MmSi--— 7~^-~%. because nature has made it impossible

entrance into that world which con- ^SJfe v»^v' " ' <%&~ ~ f°r them to be like her. Handsome

siders itself, not perhaps better, but ■—-» / she is undoubtedly, with the beauty

certainly good. Her mother has pro- that comes of perfect health undis,

apt to put to shame even those of her male companions who have

devoted a lifetime to the earnest study of these supreme matters.

In imitation of these gentlemen she will assure those who care to

listen to her, that she has had a real bad day, not having managed

to get on to a single winner, and that if it hadn't been for a fluke

in backing Tantivy, one, two, three, she would have been reduced

to a twopence in the pound condition of beggary. She will then

forget her imaginary losses, and will listen with amusement and

interest while a smooth-faced lad criticises with as much severity

as he can command in the intervals of his cigarettes the dress,

appearance, and general character of a lady whom she happens to

dislike. On the following day she will visit Hurlingham in order

to be looked at as a spectator at a polo match, in which she has no

interest whatever. After this she is entertained at dinner together

with a select party, which includes the young married lady who is

her bosom friend and occasional chaperon, by a middle-aged dandy

of somewhat shady antecedents, but of great wealth and undoubted

position. On Sunday mornings she may not always go to Church,

but she makes up for this_ neglect by the perfect regularity of her

attendance at Church parade. In the afternoon she will go to

Tattersall's to inspect horses. Ascot could not continue without

her, and Goodwood would crumble into ruins if she were absent.

This at least is her opinion, and thus the months flit by and leave

her just as wise as they found her. For she never reads a book,

and illustrates by constant practice her belief that the fashionable

intelligence of the Morning Post is a

bably discovered long since that the task of being thwarted by

her daughter is an intolerable addition to her social burdens. She

therefore permits her, with as much resignation as she can command,

to take her own course in all those matters that do not conflict

directly with the maternal plans, and she may even come to take a

pride in the bold and dashing independence by which her daughter

seeks to relieve her of all responsibility, if not of all anxiety.

It is naturally during the London Season that the life of the

Hurlingham Girl is at its fullest and best. On week-day mornings

she is a frequent attendant in the Row, the means of her father

being apparently sufficient to provide her with a sleek and showy

Park hack and an irreproachable groom. Thence she hastens home

to rest and dawdle until the hour arrives for luncheon, to which

meal she has invited the youth who happens to be temporarily

dancing attendance upon her, for it is understood in many houses

that luncheon is an open meal for which no formal invitation

from a parent is necessary. In the_ afternoon there is always a

bazaar, an amateur concert, an exhibition, a fashionable matinee or a

Society tea-party to be visited. For the evening there are dinners,

and. theatres, and an endless succession of_ dances, at which the

flowers, the suppers, and the general decorations possess as much or

as little variety as the conversation of those who overcrowd the

rooms to an accompaniment of dance-music that may once have

been new.

But of course there are distractions. Now and again Society seeks

relief from its load of care by emigrating en masse for the day to

a race-meeting at Sandown or Kempton. There the Hurlingham

Girl is as much at home as though she were native to the spot,

sprung, as it were, from the very turf itself. The interest she

takes or pretends to take in racing is something astounding. For in

truth she knows nothing about horses, their points, their pedigrees,

or their performances. Yet she chatters about them and their races,

their jockeys, their owners, the weight they carry, their tempers,

and the state of the betting market, with a glib assurance which is

turbed by thoughts of the why and the wherefore, or by anticipa-

tions of a troublesome to-morrow. Yet to the casual observer who

beholds this admirably decorated creature, her conversation is dis-

appointing. She revels in slang. Catch-words and phrases which

are not called vulgar only because the better classes use them, come

trippingly, but never with a pleasant effect from her lips. Nor has

she that sense of reticence which is said to have been the dis-

tinguishing mark of unmarried girlhood at some former period.

That she should talk frivolously on great subjects, if she talks on

them at all, is only to be expected. It would be well if her curiosity

and her conversation left untouched delicate matters, the existence

of which Bhe may suspect but ought certainly to ignore.

After she has thus flaunted her brilliant health and beauty through

several Seasons, she may begin to tire of an existence, which in

spite of its general freedom, is subject to certain restraints. She

therefore decides to emancipate herself by submitting to a husband.

She finds no difficulty, with the assistance of her mother, in discard-

ing the penniless subaltern who has devoted himself to her, and

whom she has induced to believe that she preferred to the

whole world. Having received an offer from a gentleman of pre-

sentable looks and immense possessions, she promptly accepts it,

and gains to her own surprise a considerable reputation for judgment

and. discretion. It is quite possible that after a year or two of giddy

married life she may decline gradually^ into a British Matron,

respected alike on account of her increasing family, and her sub-

stantial appearance_._

The Box the Fateee of the Mak.—The Chairman of the Infant

Insurance Committee, asked a skilled witness, "Is a man his own

child, or another person's child?" This led to an altercation, and

the room had to be cleared while the question was debated. On the

return of the Public, the query was repeated without a satisfactory

result. And yet the evident answer is, that he is another person's

child, except when he is "a self-made man."

vol,, xcrx.

E

Werk/Gegenstand/Objekt

Titel

Titel/Objekt

Punch

Weitere Titel/Paralleltitel

Serientitel

Punch

Sachbegriff/Objekttyp

Inschrift/Wasserzeichen

Aufbewahrung/Standort

Aufbewahrungsort/Standort (GND)

Inv. Nr./Signatur

H 634-3 Folio

Objektbeschreibung

Maß-/Formatangaben

Auflage/Druckzustand

Werktitel/Werkverzeichnis

Herstellung/Entstehung

Künstler/Urheber/Hersteller (GND)

Entstehungsdatum

um 1890

Entstehungsdatum (normiert)

1880 - 1900

Entstehungsort (GND)

Auftrag

Publikation

Fund/Ausgrabung

Provenienz

Restaurierung

Sammlung Eingang

Ausstellung

Bearbeitung/Umgestaltung

Thema/Bildinhalt

Thema/Bildinhalt (GND)

Literaturangabe

Rechte am Objekt

Aufnahmen/Reproduktionen

Künstler/Urheber (GND)

Reproduktionstyp

Digitales Bild

Rechtsstatus

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Creditline

Punch, 99.1890, July 26, 1890, S. 37

Beziehungen

Erschließung

Lizenz

CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication

Rechteinhaber

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg