The Two Paynes,

by Austin Dobson

A foot-note to this reference—one of those pro-

fuse annotations which, it is shrewdly suspected,

furnished the real pretext of the poem—describes

Payne as a " Trypho Emeritus." He is also de-

clared to have been " one of the best and honestest

men living," " to whom, as a bookseller, learning

is under considerable obligations."

Not the least of these obligations is his protec-

tion and encouragement of his exceedingly eccen-

tric and even disreputable namesake, Roger Payne

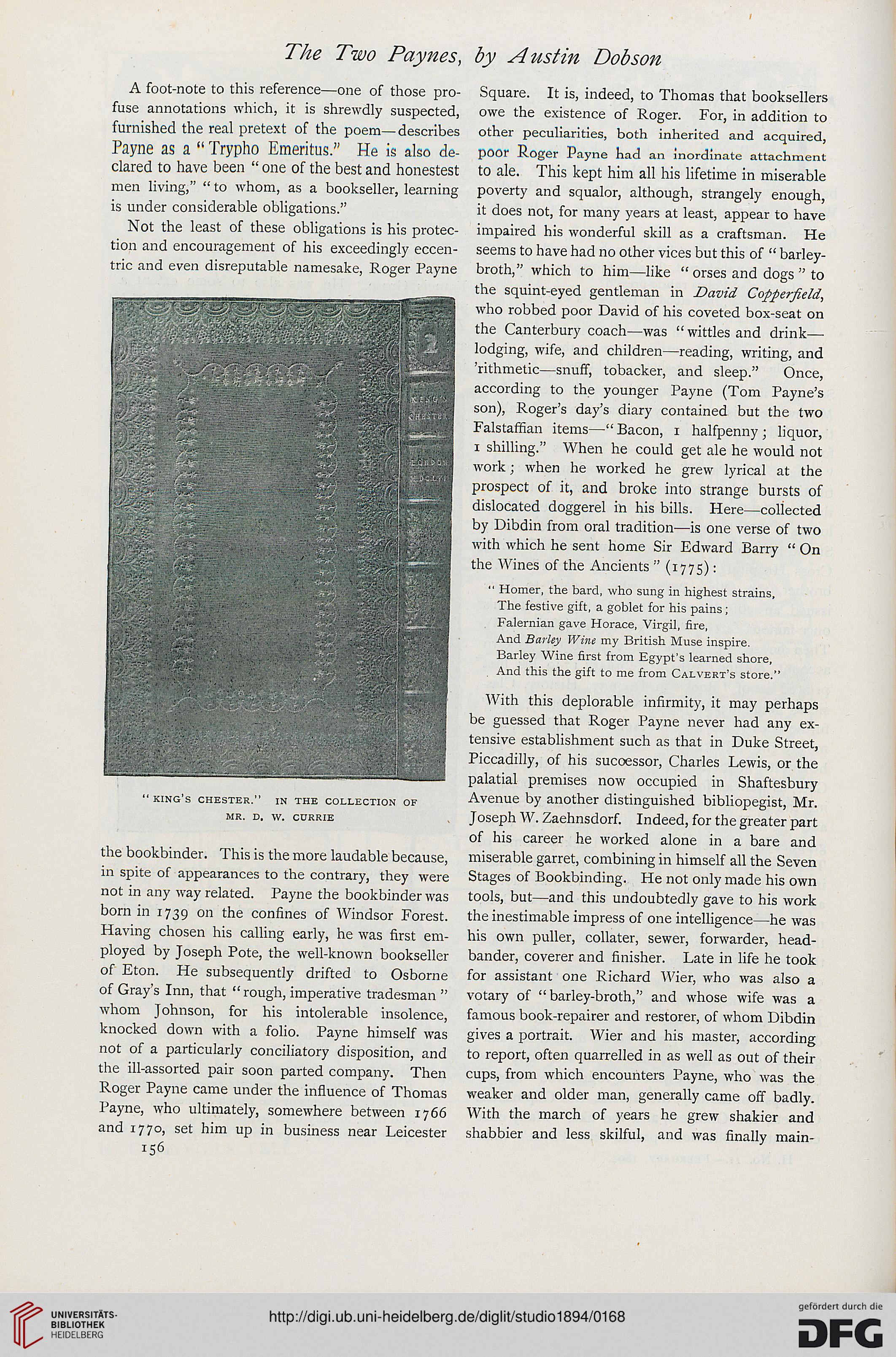

" king's chester." in the collection of

mr. d, w. currie

the bookbinder. This is the more laudable because,

in spite of appearances to the contrary, they were

not in any way related. Payne the bookbinder was

born in 1739 on the confines of Windsor Forest.

Having chosen his calling early, he was first em-

ployed by Joseph Pote, the well-known bookseller

of Eton. He subsequently drifted to Osborne

of Gray's Inn, that "rough, imperative tradesman "

whom Johnson, for his intolerable insolence,

knocked down with a folio. Payne himself was

not of a particularly conciliatory disposition, and

the ill-assorted pair soon parted company. Then

Roger Payne came under the influence of Thomas

Payne, who ultimately, somewhere between 1766

and 1770, set him up in business near Leicester

1S6

Square. It is, indeed, to Thomas that booksellers

owe the existence of Roger. For, in addition to

other peculiarities, both inherited and acquired,

poor Roger Payne had an inordinate attachment

to ale. This kept him all his lifetime in miserable

poverty and squalor, although, strangely enough,

it does not, for many years at least, appear to have

impaired his wonderful skill as a craftsman. He

seems to have had no other vices but this of " barley-

broth," which to him—like " orses and dogs " to

the squint-eyed gentleman in David Coppe7-field,

who robbed poor David of his coveted box-seat on

the Canterbury coach—was "wittlesand drink—

lodging, wife, and children—reading, writing, and

'rithmetic—snuff, tobacker, and sleep." Once,

according to the younger Payne (Tom Payne's

son), Roger's day's diary contained but the two

Falstaffian items—" Bacon, 1 halfpenny ; liquor,

1 shilling." When he could get ale he would not

work; when he worked he grew lyrical at the

prospect of it, and broke into strange bursts of

dislocated doggerel in his bills. Here—collected

by Dibdin from oral tradition—is one verse of two

with which he sent home Sir Edward Barry " On

the Wines of the Ancients " (1775):

" Homer, the bard, who sung in highest strains,

The festive gift, a goblet for his pains ;

Falernian gave Horace, Virgil, fire,

And Barley Wine my British Muse inspire.

Barley Wine first from Egypt's learned shore,

And this the gift to me from Calvert's store."

With this deplorable infirmity, it may perhaps

be guessed that Roger Payne never had any ex-

tensive establishment such as that in Duke Street,

Piccadilly, of his successor, Charles Lewis, or the

palatial premises now occupied in Shaftesbury

Avenue by another distinguished bibliopegist, Mr.

Joseph W. Zaehnsdorf. Indeed, for the greater part

of his career he worked alone in a bare and

miserable garret, combining in himself all the Seven

Stages of Bookbinding. He not only made his own

tools, but—and this undoubtedly gave to his work

the inestimable impress of one intelligence—he was

his own puller, collater, sewer, forwarder, head-

bander, coverer and finisher. Late in life he took

for assistant one Richard Wier, who was also a

votary of " barley-broth," and whose wife was a

famous book-repairer and restorer, of whom Dibdin

gives a portrait. Wier and his master, according

to report, often quarrelled in as well as out of their

cups, from which encounters Payne, who was the

weaker and older man, generally came off badly.

With the march of years he grew shakier and

shabbier and less skilful, and was finally main-

by Austin Dobson

A foot-note to this reference—one of those pro-

fuse annotations which, it is shrewdly suspected,

furnished the real pretext of the poem—describes

Payne as a " Trypho Emeritus." He is also de-

clared to have been " one of the best and honestest

men living," " to whom, as a bookseller, learning

is under considerable obligations."

Not the least of these obligations is his protec-

tion and encouragement of his exceedingly eccen-

tric and even disreputable namesake, Roger Payne

" king's chester." in the collection of

mr. d, w. currie

the bookbinder. This is the more laudable because,

in spite of appearances to the contrary, they were

not in any way related. Payne the bookbinder was

born in 1739 on the confines of Windsor Forest.

Having chosen his calling early, he was first em-

ployed by Joseph Pote, the well-known bookseller

of Eton. He subsequently drifted to Osborne

of Gray's Inn, that "rough, imperative tradesman "

whom Johnson, for his intolerable insolence,

knocked down with a folio. Payne himself was

not of a particularly conciliatory disposition, and

the ill-assorted pair soon parted company. Then

Roger Payne came under the influence of Thomas

Payne, who ultimately, somewhere between 1766

and 1770, set him up in business near Leicester

1S6

Square. It is, indeed, to Thomas that booksellers

owe the existence of Roger. For, in addition to

other peculiarities, both inherited and acquired,

poor Roger Payne had an inordinate attachment

to ale. This kept him all his lifetime in miserable

poverty and squalor, although, strangely enough,

it does not, for many years at least, appear to have

impaired his wonderful skill as a craftsman. He

seems to have had no other vices but this of " barley-

broth," which to him—like " orses and dogs " to

the squint-eyed gentleman in David Coppe7-field,

who robbed poor David of his coveted box-seat on

the Canterbury coach—was "wittlesand drink—

lodging, wife, and children—reading, writing, and

'rithmetic—snuff, tobacker, and sleep." Once,

according to the younger Payne (Tom Payne's

son), Roger's day's diary contained but the two

Falstaffian items—" Bacon, 1 halfpenny ; liquor,

1 shilling." When he could get ale he would not

work; when he worked he grew lyrical at the

prospect of it, and broke into strange bursts of

dislocated doggerel in his bills. Here—collected

by Dibdin from oral tradition—is one verse of two

with which he sent home Sir Edward Barry " On

the Wines of the Ancients " (1775):

" Homer, the bard, who sung in highest strains,

The festive gift, a goblet for his pains ;

Falernian gave Horace, Virgil, fire,

And Barley Wine my British Muse inspire.

Barley Wine first from Egypt's learned shore,

And this the gift to me from Calvert's store."

With this deplorable infirmity, it may perhaps

be guessed that Roger Payne never had any ex-

tensive establishment such as that in Duke Street,

Piccadilly, of his successor, Charles Lewis, or the

palatial premises now occupied in Shaftesbury

Avenue by another distinguished bibliopegist, Mr.

Joseph W. Zaehnsdorf. Indeed, for the greater part

of his career he worked alone in a bare and

miserable garret, combining in himself all the Seven

Stages of Bookbinding. He not only made his own

tools, but—and this undoubtedly gave to his work

the inestimable impress of one intelligence—he was

his own puller, collater, sewer, forwarder, head-

bander, coverer and finisher. Late in life he took

for assistant one Richard Wier, who was also a

votary of " barley-broth," and whose wife was a

famous book-repairer and restorer, of whom Dibdin

gives a portrait. Wier and his master, according

to report, often quarrelled in as well as out of their

cups, from which encounters Payne, who was the

weaker and older man, generally came off badly.

With the march of years he grew shakier and

shabbier and less skilful, and was finally main-