Awards in " The Studio" Prize Competitions

, volume of duets be placed upon it; while the

lighting is, as a rule, so awkwardly contrived that

the light is either too far off to afford half the illu-

mination it should yield, or else so dazzling to the

eyes of the player that the printed pages between

seem comparatively obscure.

Yet some of the early pianofortes—the old

square, the cottage, and even the grand—survive

to show that it has been done well. If space per-

mitted one might illustrate some really beautiful

Wornum and early Broadwood pianos, or, going

farther back, many an old harpischord and spinnet.

But in early pianos no massive iron framing like

that required to-day hampered the designer, who

was free to adopt graceful proportions, which

would be inadequate for the structure we now know.

Therefore to attempt to design cases on these

models were obviously futile, and the artist who

shall succeed in making the pianoforte a thing of

beauty, has a superlatively difficult task before

him.

Some practical reasons for the poor average

observable in the designs of modern pianos are

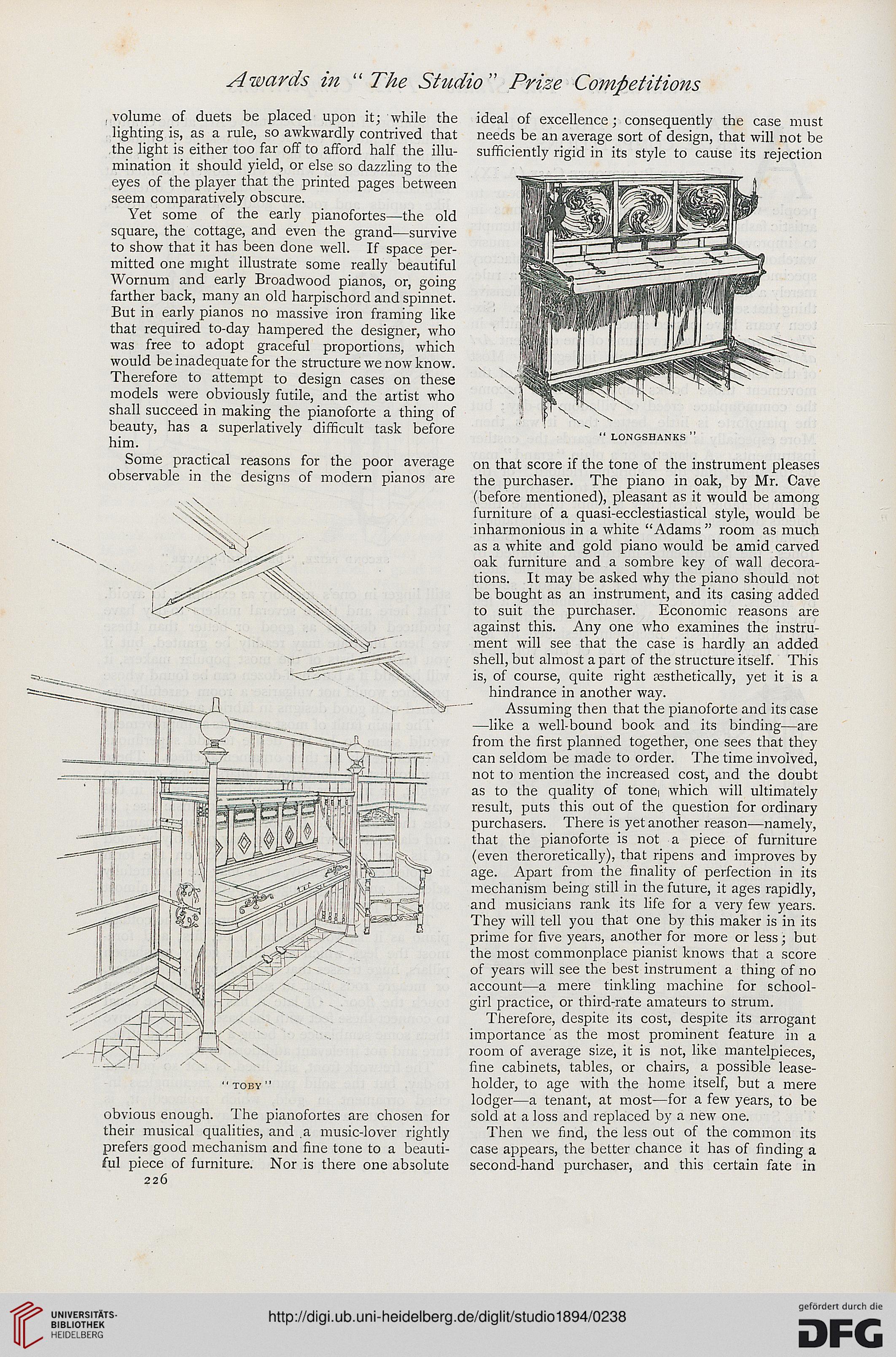

" toby "

obvious enough. The pianofortes are chosen for

their musical qualities, and a music-lover rightly

prefers good mechanism and fine tone to a beauti-

ful piece of furniture. Nor is there one absolute

226

ideal of excellence; consequently the case must

needs be an average sort of design, that will not be

sufficiently rigid in its style to cause its rejection

" LONGSHANKS "

on that score if the tone of the instrument pleases

the purchaser. The piano in oak, by Mr. Cave

(before mentioned), pleasant as it would be among

furniture of a quasi-ecclestiastical style, would be

inharmonious in a white "Adams" room as much

as a white and gold piano would be amid carved

oak furniture and a sombre key of wall decora-

tions. It may be asked why the piano should not

be bought as an instrument, and its casing added

to suit the purchaser. Economic reasons are

against this. Any one who examines the instru-

ment will see that the case is hardly an added

shell, but almost a part of the structure itself. This

is, of course, quite right aesthetically, yet it is a

hindrance in another way.

Assuming then that the pianoforte and its case

—like a well-bound book and its binding—are

from the first planned together, one sees that they

can seldom be made to order. The time involved,

not to mention the increased cost, and the doubt

as to the quality of tonei which will ultimately

result, puts this out of the question for ordinary

purchasers. There is yet another reason—namely,

that the pianoforte is not a piece of furniture

(even theroretically), that ripens and improves by

age. Apart from the finality of perfection in its

mechanism being still in the future, it ages rapidly,

and musicians rank its life for a very few years.

They will tell you that one by this maker is in its

prime for five years, another for more or less; but

the most commonplace pianist knows that a score

of years will see the best instrument a thing of no

account—a mere tinkling machine for school-

girl practice, or third-rate amateurs to strum.

Therefore, despite its cost, despite its arrogant

importance as the most prominent feature in a

room of average size, it is not, like mantelpieces,

fine cabinets, tables, or chairs, a possible lease-

holder, to age with the home itself, but a mere

lodger—a tenant, at most—for a few years, to be

sold at a loss and replaced by a new one.

Then we find, the less out of the common its

case appears, the better chance it has of finding a

second-hand purchaser, and this certain fate in

, volume of duets be placed upon it; while the

lighting is, as a rule, so awkwardly contrived that

the light is either too far off to afford half the illu-

mination it should yield, or else so dazzling to the

eyes of the player that the printed pages between

seem comparatively obscure.

Yet some of the early pianofortes—the old

square, the cottage, and even the grand—survive

to show that it has been done well. If space per-

mitted one might illustrate some really beautiful

Wornum and early Broadwood pianos, or, going

farther back, many an old harpischord and spinnet.

But in early pianos no massive iron framing like

that required to-day hampered the designer, who

was free to adopt graceful proportions, which

would be inadequate for the structure we now know.

Therefore to attempt to design cases on these

models were obviously futile, and the artist who

shall succeed in making the pianoforte a thing of

beauty, has a superlatively difficult task before

him.

Some practical reasons for the poor average

observable in the designs of modern pianos are

" toby "

obvious enough. The pianofortes are chosen for

their musical qualities, and a music-lover rightly

prefers good mechanism and fine tone to a beauti-

ful piece of furniture. Nor is there one absolute

226

ideal of excellence; consequently the case must

needs be an average sort of design, that will not be

sufficiently rigid in its style to cause its rejection

" LONGSHANKS "

on that score if the tone of the instrument pleases

the purchaser. The piano in oak, by Mr. Cave

(before mentioned), pleasant as it would be among

furniture of a quasi-ecclestiastical style, would be

inharmonious in a white "Adams" room as much

as a white and gold piano would be amid carved

oak furniture and a sombre key of wall decora-

tions. It may be asked why the piano should not

be bought as an instrument, and its casing added

to suit the purchaser. Economic reasons are

against this. Any one who examines the instru-

ment will see that the case is hardly an added

shell, but almost a part of the structure itself. This

is, of course, quite right aesthetically, yet it is a

hindrance in another way.

Assuming then that the pianoforte and its case

—like a well-bound book and its binding—are

from the first planned together, one sees that they

can seldom be made to order. The time involved,

not to mention the increased cost, and the doubt

as to the quality of tonei which will ultimately

result, puts this out of the question for ordinary

purchasers. There is yet another reason—namely,

that the pianoforte is not a piece of furniture

(even theroretically), that ripens and improves by

age. Apart from the finality of perfection in its

mechanism being still in the future, it ages rapidly,

and musicians rank its life for a very few years.

They will tell you that one by this maker is in its

prime for five years, another for more or less; but

the most commonplace pianist knows that a score

of years will see the best instrument a thing of no

account—a mere tinkling machine for school-

girl practice, or third-rate amateurs to strum.

Therefore, despite its cost, despite its arrogant

importance as the most prominent feature in a

room of average size, it is not, like mantelpieces,

fine cabinets, tables, or chairs, a possible lease-

holder, to age with the home itself, but a mere

lodger—a tenant, at most—for a few years, to be

sold at a loss and replaced by a new one.

Then we find, the less out of the common its

case appears, the better chance it has of finding a

second-hand purchaser, and this certain fate in