James McNeill Whistler

ling or vision proceeded from traditional ground, proceed less experimentally and in the dark,

He used paint not in order to produce a beautiful he dismiss the immediate pre-occupation of nature

surface characteristic of oil paint, nor as if it were and paint from sketches, his touch loses the

an otherwise negligible means of representation: nerve which, under the stimulus of observation,

in the pursuit of the one aim he achieved the found an interesting notation—even if it seem

other, and in his work we have at once the only reasonable to imitate in cool blood the unconscious

beautiful painting, and well-nigh all that a whole felicities of the sketch, his hand will scarcely

generation of painting in England, from i860 to attain them. Modern painting seems to demand

1890, has had to tell us of the aspect of things. the constant inspiration of nature, and the clean

So it is that when one sees again a landscape of sacrifice every time of the painting that has not

Whistler's, a Thames nocturne, or the old Battersea completely achieved its aim. Even were there no

Bridge, pictures which have discovered for us those tradition of many sittings, the portrait of Miss

appearances of the town which our eyes now most Alexander is too full of invention, the grey, the

welcome, one wavers for an explanation of its green, the white, the black are too exquisitely

exquisite dignity. Does this sense of a repose that sought, the surface is too inexplicable and various

reaches behind the flight of time, and beyond the in its fitness, to have come into existence without

distraction of circumstances, lie in the precious elaboration upon elaboration. But the labour is

vision discovered in the life that is most

familiar to us, or is it an effect of the just-

ness with which the brash has touched

the canvas ? It is as if the touches had

been long prepared, had waited ready, one

might almost fancy from the beginning of

time, for the eye that should one day see

the river and its buildings so shape them-

selves and take on such colours. The paint

slips into its place, it is there inevitably as

the evening upon the water, no longer the

pigment, as it was upon the palette, but a

surface of subtle texture, airy, living with

the life of the hand that created it.

The portrait of Miss Alexander shows

that Whistler was able to win what much

labour and research only could yield him,

without losing from his brush its acute

economy, without disturbance to the un-

troubled charm of surface. The modern

painter—whose inclination it is to aim,

with his first touch, at a nearer realisation

of values observed than ancient painting,

perhaps, cared to reach even in its final

operations—encounters difficulties when-

ever for any reason he feels called upon to

prolong his labour beyond the point to

which the first inspiration of his subject

has directly led him. If he continues to

paint on with his solid mixtures he troubles

his colour and his surface; the paint that

is already on the canvas is of no service

to him, for it was not put there with the

intention and knowledge that it was to be

the preliminary stage to the achievement of

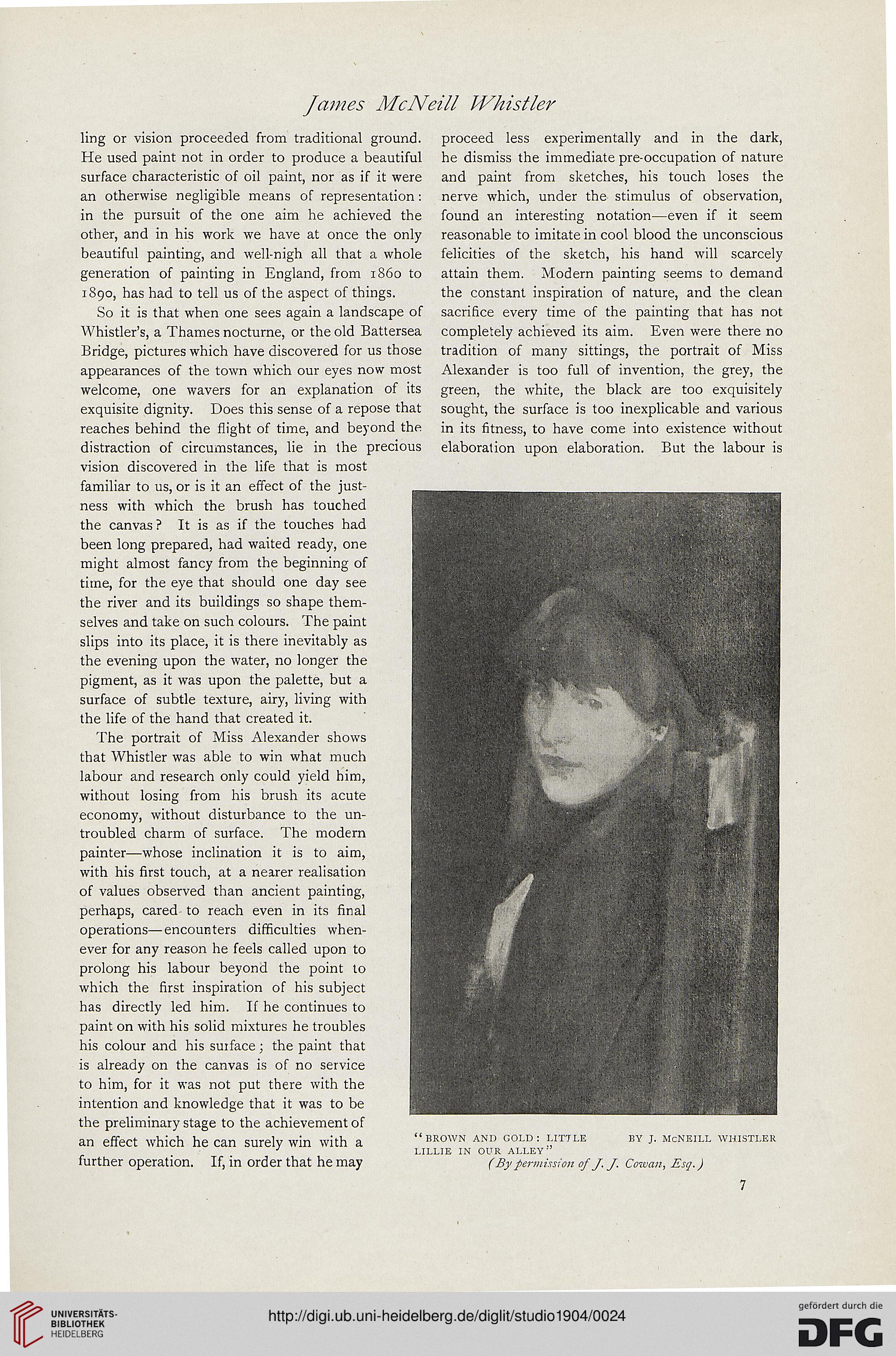

an effect which he can surely win with a "brown and gold: little by j. mcneill whistler

' lillie in our alley''

further operation. If, in order that he may (By permission of J. J. Cowan, Esq.)

ling or vision proceeded from traditional ground, proceed less experimentally and in the dark,

He used paint not in order to produce a beautiful he dismiss the immediate pre-occupation of nature

surface characteristic of oil paint, nor as if it were and paint from sketches, his touch loses the

an otherwise negligible means of representation: nerve which, under the stimulus of observation,

in the pursuit of the one aim he achieved the found an interesting notation—even if it seem

other, and in his work we have at once the only reasonable to imitate in cool blood the unconscious

beautiful painting, and well-nigh all that a whole felicities of the sketch, his hand will scarcely

generation of painting in England, from i860 to attain them. Modern painting seems to demand

1890, has had to tell us of the aspect of things. the constant inspiration of nature, and the clean

So it is that when one sees again a landscape of sacrifice every time of the painting that has not

Whistler's, a Thames nocturne, or the old Battersea completely achieved its aim. Even were there no

Bridge, pictures which have discovered for us those tradition of many sittings, the portrait of Miss

appearances of the town which our eyes now most Alexander is too full of invention, the grey, the

welcome, one wavers for an explanation of its green, the white, the black are too exquisitely

exquisite dignity. Does this sense of a repose that sought, the surface is too inexplicable and various

reaches behind the flight of time, and beyond the in its fitness, to have come into existence without

distraction of circumstances, lie in the precious elaboration upon elaboration. But the labour is

vision discovered in the life that is most

familiar to us, or is it an effect of the just-

ness with which the brash has touched

the canvas ? It is as if the touches had

been long prepared, had waited ready, one

might almost fancy from the beginning of

time, for the eye that should one day see

the river and its buildings so shape them-

selves and take on such colours. The paint

slips into its place, it is there inevitably as

the evening upon the water, no longer the

pigment, as it was upon the palette, but a

surface of subtle texture, airy, living with

the life of the hand that created it.

The portrait of Miss Alexander shows

that Whistler was able to win what much

labour and research only could yield him,

without losing from his brush its acute

economy, without disturbance to the un-

troubled charm of surface. The modern

painter—whose inclination it is to aim,

with his first touch, at a nearer realisation

of values observed than ancient painting,

perhaps, cared to reach even in its final

operations—encounters difficulties when-

ever for any reason he feels called upon to

prolong his labour beyond the point to

which the first inspiration of his subject

has directly led him. If he continues to

paint on with his solid mixtures he troubles

his colour and his surface; the paint that

is already on the canvas is of no service

to him, for it was not put there with the

intention and knowledge that it was to be

the preliminary stage to the achievement of

an effect which he can surely win with a "brown and gold: little by j. mcneill whistler

' lillie in our alley''

further operation. If, in order that he may (By permission of J. J. Cowan, Esq.)