138

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

[April 3, 1869.

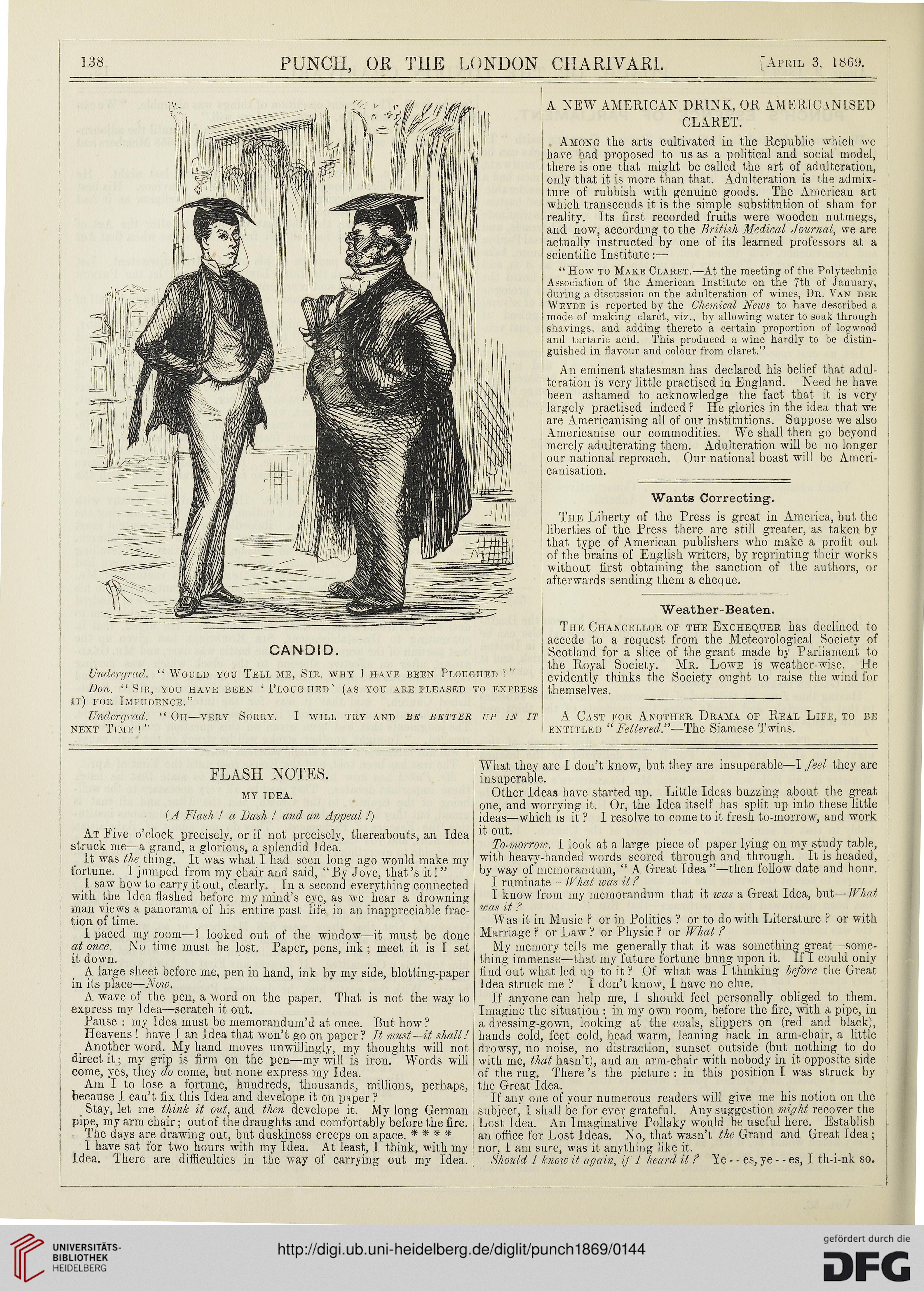

CANDID.

Undergrad. “ Would you Tell me, Sir, why I have been Ploughed ?”

Don. “ StR, you have been ‘Ploughed’ (as you are pleased to express

it) for Impudence.”

Undergrad. “ Oh—very Sorry. I will try and be better up in it

next Time ! ”

A NEW AMERICAN DRINK, OR AMERICANISED

CLARET.

Among the arts cultivated in the Republic which we

have had proposed to us as a political aud social model,

there is one that might be called the art of adulteration,

only that it is more than that. Adulteration is the admix-

ture of rubbish with genuine goods. The American art

which transcends it is the simple substitution of sham for

reality. Its first recorded fruits were wooden nutmegs,

and now, according to the British Medical Journal, we are

actually instructed by one of its learned professors at a

scientific Institute:—

“ How to Mare Claret.—At the meeting of the Polytechnic

Association of the American Institute on the 7th of January,

during a discussion on the adulteration of wines, Dr. Van dek

Weyde is reported by the Chemical News to have described a

mode of making claret, viz., by allowing water to soak through

shavings, and adding thereto a certain proportion of logwood

and tartaric acid. This produced a wine hardly to be distin-

guished in flavour and colour from claret.”

An eminent statesman has declared his belief that adul-

teration is very little practised in England. Need he have

been ashamed to acknowledge the fact that it is very

largely practised indeed ? He glories in the idea that we

are Americanising all of our institutions. Suppose we also

Americanise our commodities. We shall then go beyond

merely adulterating them. Adulteration will be no longer

our national reproach. Our national boast will be Ameri-

canisation.

Wants Correcting'.

The Liberty of the Press is great in America, but the

liberties of the Press there are still greater, as taken by

that type of American publishers who make a profit out

of the brains of English writers, by reprinting their works

without first obtaining the sanction of the authors, or

afterwards sending them a cheque.

Weather-Beaten.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer has declined to

accede to a request from the Meteorological Society of

Scotland for a slice of the grant made by Parliament to

the Royal Society. Mr. Lowe is weather-wise. He

evidently thinks the Society ought to raise the wind for

themselves.

A Cast for Another Drama of Real Life, to be

entitled “Fettered!’—The Siamese Twins.

FLASH NOTES.

MY IDEA.

(A Flash ! a Bash ! and an Appeal !)

At Five o’clock precisely, or if not precisely, thereabouts, an Idea

struck me—a grand, a glorious, a splendid Idea.

It was the thing. It was what I had seen long ago would make my

tortune. 1 jumped from my chair and said, “By Jove, that’s it! ”

l saw howto carry it out, clearly. In a second everything connected

with the Idea flashed before my mind’s eye, as we hear a drowning

man views a panorama of his entire past life in an inappreciable frac-

tion of time.

I paced my room—I looked out of the window—it must be done

at once. N o time must be lost. Paper, pens, ink ; meet it is I set

it down.

A large sheet before me, pen in hand, ink by my side, blotting-paper

in its place—Now.

A wave of the pen, a word on the paper. That is not the way to

express my Idea—scratch it out.

Pause : my Idea must be memorandum’d at once. But how?

Heavens ! have I an Idea that won’t go on paper? It must—it shall!

_ Another word. My hand moves unwillingly, my thoughts will not

direct it; my grip is firm on the pen—my will is iron. Words will

come, yes, they do come, but none express my Idea.

Am I to lose a fortune, hundreds, thousands, millions, perhaps,

because I can’t fix this Idea and develope it on paper ?

_ Stay, let me think it out, and then develope it. My long German

pipe, my arm chair; out of the draughts and comfortably before the fire.

The days are drawing out, but duskiness creeps on apace. * * * *

1 have sat for two hours with my Idea. At least, I think, with my

Idea. There are difficulties in the way of carrying out my Idea.

What they are I don’t know, but they are insuperable—I feel they are

insuperable.

Other Ideas have started up. Little Ideas buzzing about the great

one, and worrying it. Or, the Idea itself has split up into these little

ideas—which is it F I resolve to come to it fresh to-morrow, and work

it out.

To-morrow. I look at a large piece of paper lying on my study table,

with heavy-handed words scored through and through. It is headed,

by way of memorandum, “ A Great Idea”—then follow date and hour.

I ruminate - What was it I

I know from my memorandum that it was a Great Idea, but—What

was it ?

Was it in Music ? or in Politics ? or to do with Literature ? or with

Marriage ? or Law ? or Physic ? or What ?

My memory tells me generally that it was something great—some-

thing immense—that my future fortune hung upon it. If I could only i

find out what led up to it ? Of what was I thinking before the Great

Idea struck me ? I don’t know, I have no clue.

If anyone can help me, 1 should feel personally obliged to them.

Imagine the situation : in my own room, before the fire, with a pipe, in

a dressing-gown, looking at the coals, slippers on (red and black),

hands cold, feet cold, head warm, leaning back in arm-chair, a little

drowsy, no noise, no distraction, sunset outside (but nothing to do

with me, that hasn’t), and an arm-chair with nobody in it opposite side

of the rug. There’s the picture : in this position I was struck by

the Great Idea.

If any one of your numerous readers will give me his notion on the

subject, 1 shall be for ever grateful. Any suggestion might recover the

Lost Idea. An Imaginative Pollaky would be useful here. Establish j.

an office for Lost Ideas. No, that wasn’t the Grand and Great Idea ;

nor, I am sure, was it anything like it.

Should 1 know it again, if I heard it ? Ye - - es, ye - - es, I th-i-nk so.

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

[April 3, 1869.

CANDID.

Undergrad. “ Would you Tell me, Sir, why I have been Ploughed ?”

Don. “ StR, you have been ‘Ploughed’ (as you are pleased to express

it) for Impudence.”

Undergrad. “ Oh—very Sorry. I will try and be better up in it

next Time ! ”

A NEW AMERICAN DRINK, OR AMERICANISED

CLARET.

Among the arts cultivated in the Republic which we

have had proposed to us as a political aud social model,

there is one that might be called the art of adulteration,

only that it is more than that. Adulteration is the admix-

ture of rubbish with genuine goods. The American art

which transcends it is the simple substitution of sham for

reality. Its first recorded fruits were wooden nutmegs,

and now, according to the British Medical Journal, we are

actually instructed by one of its learned professors at a

scientific Institute:—

“ How to Mare Claret.—At the meeting of the Polytechnic

Association of the American Institute on the 7th of January,

during a discussion on the adulteration of wines, Dr. Van dek

Weyde is reported by the Chemical News to have described a

mode of making claret, viz., by allowing water to soak through

shavings, and adding thereto a certain proportion of logwood

and tartaric acid. This produced a wine hardly to be distin-

guished in flavour and colour from claret.”

An eminent statesman has declared his belief that adul-

teration is very little practised in England. Need he have

been ashamed to acknowledge the fact that it is very

largely practised indeed ? He glories in the idea that we

are Americanising all of our institutions. Suppose we also

Americanise our commodities. We shall then go beyond

merely adulterating them. Adulteration will be no longer

our national reproach. Our national boast will be Ameri-

canisation.

Wants Correcting'.

The Liberty of the Press is great in America, but the

liberties of the Press there are still greater, as taken by

that type of American publishers who make a profit out

of the brains of English writers, by reprinting their works

without first obtaining the sanction of the authors, or

afterwards sending them a cheque.

Weather-Beaten.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer has declined to

accede to a request from the Meteorological Society of

Scotland for a slice of the grant made by Parliament to

the Royal Society. Mr. Lowe is weather-wise. He

evidently thinks the Society ought to raise the wind for

themselves.

A Cast for Another Drama of Real Life, to be

entitled “Fettered!’—The Siamese Twins.

FLASH NOTES.

MY IDEA.

(A Flash ! a Bash ! and an Appeal !)

At Five o’clock precisely, or if not precisely, thereabouts, an Idea

struck me—a grand, a glorious, a splendid Idea.

It was the thing. It was what I had seen long ago would make my

tortune. 1 jumped from my chair and said, “By Jove, that’s it! ”

l saw howto carry it out, clearly. In a second everything connected

with the Idea flashed before my mind’s eye, as we hear a drowning

man views a panorama of his entire past life in an inappreciable frac-

tion of time.

I paced my room—I looked out of the window—it must be done

at once. N o time must be lost. Paper, pens, ink ; meet it is I set

it down.

A large sheet before me, pen in hand, ink by my side, blotting-paper

in its place—Now.

A wave of the pen, a word on the paper. That is not the way to

express my Idea—scratch it out.

Pause : my Idea must be memorandum’d at once. But how?

Heavens ! have I an Idea that won’t go on paper? It must—it shall!

_ Another word. My hand moves unwillingly, my thoughts will not

direct it; my grip is firm on the pen—my will is iron. Words will

come, yes, they do come, but none express my Idea.

Am I to lose a fortune, hundreds, thousands, millions, perhaps,

because I can’t fix this Idea and develope it on paper ?

_ Stay, let me think it out, and then develope it. My long German

pipe, my arm chair; out of the draughts and comfortably before the fire.

The days are drawing out, but duskiness creeps on apace. * * * *

1 have sat for two hours with my Idea. At least, I think, with my

Idea. There are difficulties in the way of carrying out my Idea.

What they are I don’t know, but they are insuperable—I feel they are

insuperable.

Other Ideas have started up. Little Ideas buzzing about the great

one, and worrying it. Or, the Idea itself has split up into these little

ideas—which is it F I resolve to come to it fresh to-morrow, and work

it out.

To-morrow. I look at a large piece of paper lying on my study table,

with heavy-handed words scored through and through. It is headed,

by way of memorandum, “ A Great Idea”—then follow date and hour.

I ruminate - What was it I

I know from my memorandum that it was a Great Idea, but—What

was it ?

Was it in Music ? or in Politics ? or to do with Literature ? or with

Marriage ? or Law ? or Physic ? or What ?

My memory tells me generally that it was something great—some-

thing immense—that my future fortune hung upon it. If I could only i

find out what led up to it ? Of what was I thinking before the Great

Idea struck me ? I don’t know, I have no clue.

If anyone can help me, 1 should feel personally obliged to them.

Imagine the situation : in my own room, before the fire, with a pipe, in

a dressing-gown, looking at the coals, slippers on (red and black),

hands cold, feet cold, head warm, leaning back in arm-chair, a little

drowsy, no noise, no distraction, sunset outside (but nothing to do

with me, that hasn’t), and an arm-chair with nobody in it opposite side

of the rug. There’s the picture : in this position I was struck by

the Great Idea.

If any one of your numerous readers will give me his notion on the

subject, 1 shall be for ever grateful. Any suggestion might recover the

Lost Idea. An Imaginative Pollaky would be useful here. Establish j.

an office for Lost Ideas. No, that wasn’t the Grand and Great Idea ;

nor, I am sure, was it anything like it.

Should 1 know it again, if I heard it ? Ye - - es, ye - - es, I th-i-nk so.

Werk/Gegenstand/Objekt

Titel

Titel/Objekt

Candid

Weitere Titel/Paralleltitel

Serientitel

Punch

Sachbegriff/Objekttyp

Inschrift/Wasserzeichen

Aufbewahrung/Standort

Aufbewahrungsort/Standort (GND)

Inv. Nr./Signatur

H 634-3 Folio

Objektbeschreibung

Maß-/Formatangaben

Auflage/Druckzustand

Werktitel/Werkverzeichnis

Herstellung/Entstehung

Künstler/Urheber/Hersteller (GND)

Entstehungsdatum

um 1869

Entstehungsdatum (normiert)

1864 - 1874

Entstehungsort (GND)

Auftrag

Publikation

Fund/Ausgrabung

Provenienz

Restaurierung

Sammlung Eingang

Ausstellung

Bearbeitung/Umgestaltung

Thema/Bildinhalt

Thema/Bildinhalt (GND)

Literaturangabe

Rechte am Objekt

Aufnahmen/Reproduktionen

Künstler/Urheber (GND)

Reproduktionstyp

Digitales Bild

Rechtsstatus

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Creditline

Punch, 56.1869, April 3, 1869, S. 138

Beziehungen

Erschließung

Lizenz

CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication

Rechteinhaber

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg