Kunst und Handwerk

A.D. 1851

Teil der ägyptischen und ostasiatischen Kunst, dann

aber in ihrem ganzen Umfang die vorderasiatische

Kunst und der allergrößte Teil der christlich-kirchlichen

Kunst des Mittelalters und des Barocks, und zwar

nicht nur die Kunst der katholischen Kirche, sondern

auch die von Byzanz und Rußland.

A Es kann hier nicht angeführt werden, worin der

Eigenwert und der Vorzug dieser beiden Richtungen

besteht. Es soll nur konstatiert werden, daß beide

Richtungen in der ganzen Weltgeschichte der Mensch-

heit immer wieder auftreten und daß beide gleich-

berechtigt vom künstlerischen Standpunkt sind, ja in

ihrer Polarität die immer wieder sich erneuernde

Spannung der Kunst, vor allem der Plastik bedingen.

A Die deutsche Kunst, wie überhaupt der größte Teil

der europäischen Kunst hat um die Wende zum zwan-

zigsten Jahrhundert die langsame Umkehr von einer

klassizistisch-naturalistischen Schönheitskunst zu einer

stilisierten'Ausdruckskunst vollzogen. Die ersten radi-

kalen Wellen sind inzwischen verebbt. Aber ohne

Zweifel hat die deutsche Bildhauerkunst damit eine

geistige Vertiefung erfahren, die ihr erlaubt, das See-

lische, das Religiöse, das kultisch Erhabene stärker zu

fassen und monumentaler zu formen.

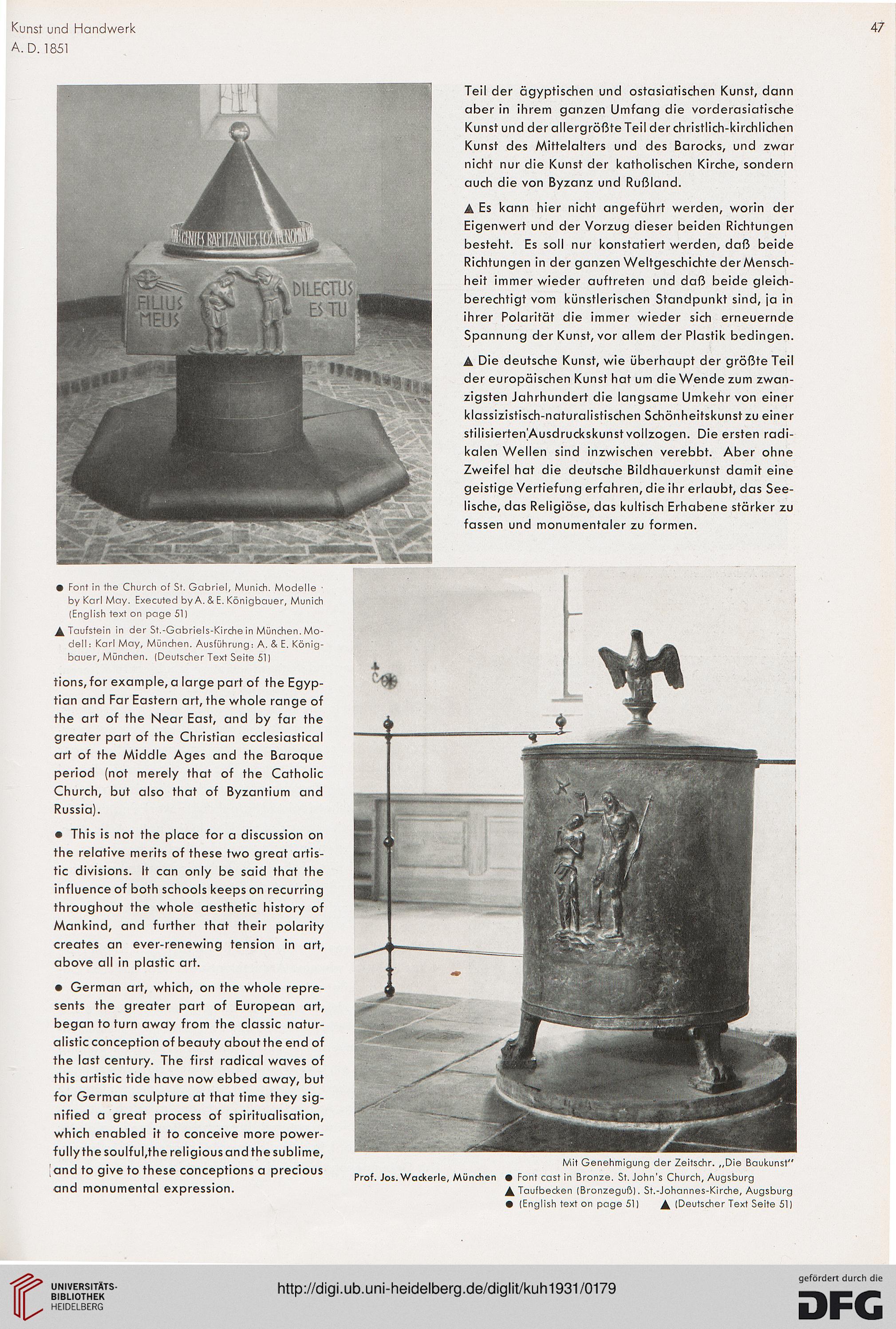

• Font in the Church of St. Gabriel, Munich. Modelle •

by Karl May. Executed by A. & E. Königbauer, Munich

(English text on page 511

A Taufstein in der St.-Gabriels-Kirche in München. Mo-

dell: Karl May, München. Ausführung: A. & E. König-

bauer, München. (Deutscher Text Seite 51)

tions,for example, a large part of the Egyp-

tian and Far Eastern art, the whole ränge of

the art of the Near East, and by far the

greater part of the Christian ecclesiastical

art of the Middle Ages and the Baroque

period (not merely that of the Catholic

Church, but also that of Byzantium and ■——

Russia).

• This is not the place for a discussion on

the relative merits of these two great artis-

tic divisions. It can only be said that the

influence of both schools keeps on recurring

throughout the whole aesthetic history of

Mankind, and further that their polarity

creates an ever-renewing tension in art,

above all in plastic art.

• German art, which, on the whole repre-

sents the greater part of European art,

began to turn away frorn the classic natur- W^^^^BEXZ..„__^j3j(H

alistic conception of beauty about the end of jS^J^R. —^ JBj

the last Century. The first radical waves of SK;

this artistic tide have nowebbed away, but Jflp ^9

for German sculpture at that time they sig-

nified a great process of spiritualisation,

which enabled it to conceive more power- HflMP^jlfl

f ully the soulf ul,the religious and the sublime,

. . . Mit Genehmigung der Zeitschr. „Die Baukunst"

and to give to these conceptions a precious prof Jos Wacker,ei München # Font cast ,n Bronze. St. John.s church| Augsburg

and monumental expression. A Taufbecken (Bronzeguß). St.-Johannes-Kirche, Augsburg

• (English text on page 51) A (Deutscher Text Seite 51)

A.D. 1851

Teil der ägyptischen und ostasiatischen Kunst, dann

aber in ihrem ganzen Umfang die vorderasiatische

Kunst und der allergrößte Teil der christlich-kirchlichen

Kunst des Mittelalters und des Barocks, und zwar

nicht nur die Kunst der katholischen Kirche, sondern

auch die von Byzanz und Rußland.

A Es kann hier nicht angeführt werden, worin der

Eigenwert und der Vorzug dieser beiden Richtungen

besteht. Es soll nur konstatiert werden, daß beide

Richtungen in der ganzen Weltgeschichte der Mensch-

heit immer wieder auftreten und daß beide gleich-

berechtigt vom künstlerischen Standpunkt sind, ja in

ihrer Polarität die immer wieder sich erneuernde

Spannung der Kunst, vor allem der Plastik bedingen.

A Die deutsche Kunst, wie überhaupt der größte Teil

der europäischen Kunst hat um die Wende zum zwan-

zigsten Jahrhundert die langsame Umkehr von einer

klassizistisch-naturalistischen Schönheitskunst zu einer

stilisierten'Ausdruckskunst vollzogen. Die ersten radi-

kalen Wellen sind inzwischen verebbt. Aber ohne

Zweifel hat die deutsche Bildhauerkunst damit eine

geistige Vertiefung erfahren, die ihr erlaubt, das See-

lische, das Religiöse, das kultisch Erhabene stärker zu

fassen und monumentaler zu formen.

• Font in the Church of St. Gabriel, Munich. Modelle •

by Karl May. Executed by A. & E. Königbauer, Munich

(English text on page 511

A Taufstein in der St.-Gabriels-Kirche in München. Mo-

dell: Karl May, München. Ausführung: A. & E. König-

bauer, München. (Deutscher Text Seite 51)

tions,for example, a large part of the Egyp-

tian and Far Eastern art, the whole ränge of

the art of the Near East, and by far the

greater part of the Christian ecclesiastical

art of the Middle Ages and the Baroque

period (not merely that of the Catholic

Church, but also that of Byzantium and ■——

Russia).

• This is not the place for a discussion on

the relative merits of these two great artis-

tic divisions. It can only be said that the

influence of both schools keeps on recurring

throughout the whole aesthetic history of

Mankind, and further that their polarity

creates an ever-renewing tension in art,

above all in plastic art.

• German art, which, on the whole repre-

sents the greater part of European art,

began to turn away frorn the classic natur- W^^^^BEXZ..„__^j3j(H

alistic conception of beauty about the end of jS^J^R. —^ JBj

the last Century. The first radical waves of SK;

this artistic tide have nowebbed away, but Jflp ^9

for German sculpture at that time they sig-

nified a great process of spiritualisation,

which enabled it to conceive more power- HflMP^jlfl

f ully the soulf ul,the religious and the sublime,

. . . Mit Genehmigung der Zeitschr. „Die Baukunst"

and to give to these conceptions a precious prof Jos Wacker,ei München # Font cast ,n Bronze. St. John.s church| Augsburg

and monumental expression. A Taufbecken (Bronzeguß). St.-Johannes-Kirche, Augsburg

• (English text on page 51) A (Deutscher Text Seite 51)