May 10, 1884.]

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

217

LETTERS TO SOME PEOPLE

About Other People’s Business.

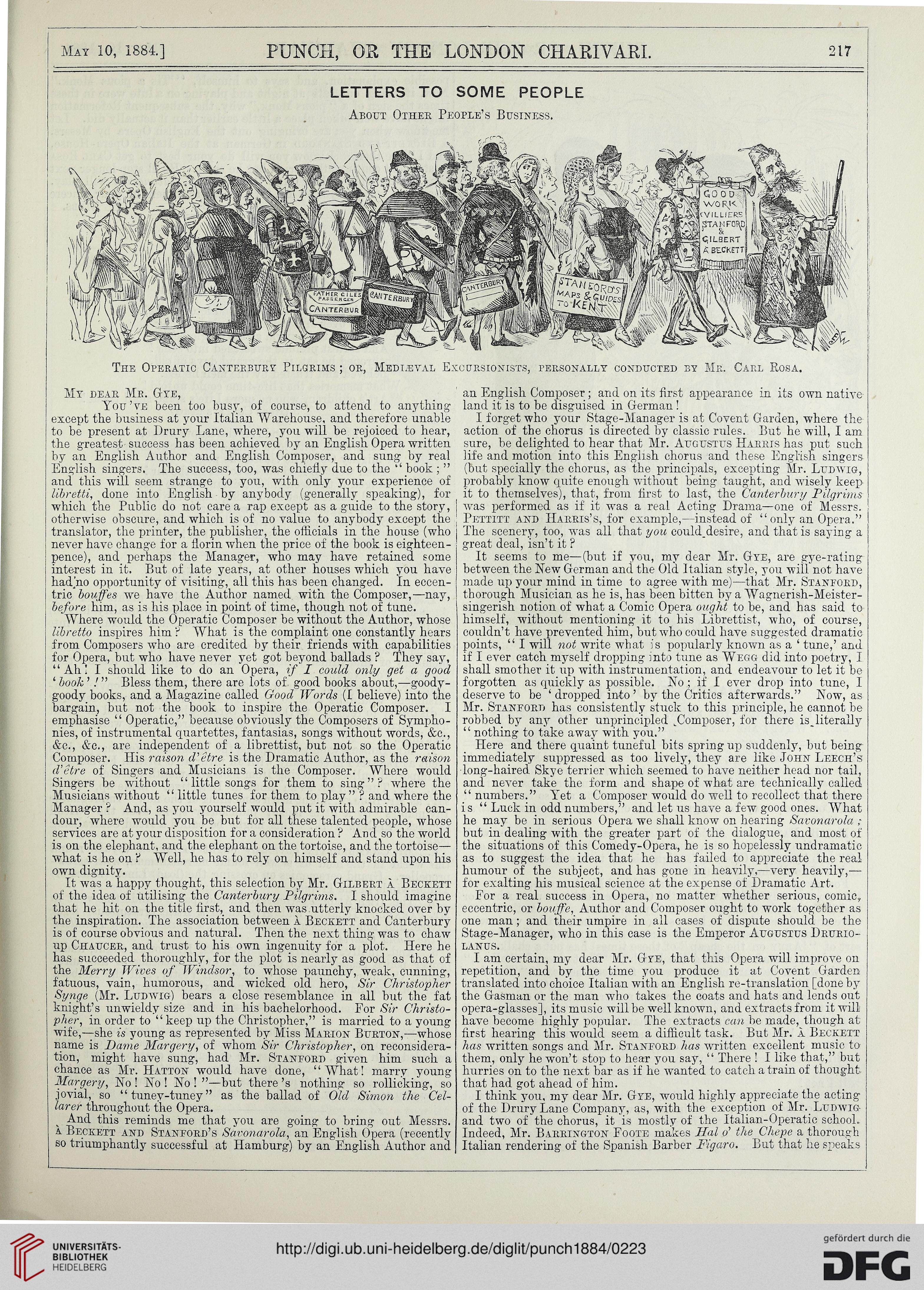

The Operatic Canterbury Pilgrims ; or, Medieval Excursionists, personally conducted by Mr. Carl Rosa.

My dear Mr. G-ye,

You’ve been too busy, of course, to attend to anything'

except the business at your Italian Warehouse, and therefore unable

to be present at Drury Lane, where, you will be rejoiced to hear,

the greatest-success has been achieved by an English Opera written

by au English Author and English Composer, and sung by real

English singers. The success, too, was chiefly due to the “ book ; ”

and this will seem strange to you, with only your experience of

libretti, done into English by anybody (generally speaking), for

which the Public do not care a rap except as a guide to the story,

otherwise obscure, and which is of no value to anybody except the

translator, the printer, the publisher, the officials in the house (who

never have change for a florin when the price of the book is eighteen-

pence), and perhaps the Manager, who may have retained some

interest in it. But of late years, at other houses which yon have

hadjio opportunity of visiting, all this has been changed. In eccen-

tric boujfes we have the Author named with the Composer,—nay,

before him, as is his place in point of time, though not of tune.

Where would the Operatic Composer be without the Author, whose

libretto inspires him ? What is the complaint one constantly hears

from Composers who are credited by their friends with capabilities

for Opera, but who have never yet got beyond ballads ? They say,

“Ah! I should like to do an Opera, if I could only get a good

1 book ’ ! ” Bless them, there are lots of good hooks about,—goody-

goody books, and a Magazine called Good Words (I believe) into the

bargain, but not the book to inspire the Operatic Composer. I

emphasise “ Operatic,” because obviously the Composers of Sympho-

nies, of instrumental quartettes, fantasias, songs without words, &c.,

&c., &c., are independent of a librettist, but not so the Operatic

Composer. His raison d'etre is the Dramatic Author, as the raison

d’etre of Singers and Musicians is the Composer. Where would

Singers be without “little songs for them to sing”? where the

Musicians without “ little tunes for them to play ” ? and where the

Manager ? And, as yon yourself would put it with admirable can-

dour, where would you be but for all these talented people, whose

services are at your disposition for a consideration ? And so the world

is on the elephant, and the elephant on the tortoise, and the tortoise—

what is he on ? Well, he has to rely on himself and stand upon his

own dignity.

It was a happy thought, this selection by Mr. Gilbert a Beckett

of the idea of utilising the Canterbury Pilgrims. I should imagine

that he hit oil the title first, and then was utterly knocked over by

tbe inspiration. The association between a Beckett and Canterbury

is of course obvious and natural. Then the next thing was to chaw

up Chaucer, and trust to his own ingenuity for a plot. Here he

has succeeded thoroughly, for the plot is nearly as good as that of

the Merry Wives of Windsor, to whose paunchy, weak, cunning,

fatuous, vain, humorous, and wicked old hero, Sir Christopher

Synge (Mr. Ludwig) bears a close resemblance in all but the fat

knight’s unwieldy size and in his bachelorhood. For Sir Christo-

pher, in order to “keep up the Christopher,” is married to a young

wife,—she is young as represented by Miss Marion Burton,—whose

name is Dame Margery, of whom Sir Christopher, on reconsidera-

tion, might have sung, had Mr. Staneord given him such a

chance as Mr. Hatton would have done, “What! marry young

Margery, No ! No ! No ! ’’—but there’s nothing so rollicking, so

jovial, so “ tuney-tuney ” as the ballad of Old Simon the Cel-

larer throughout the Opera.

And this reminds me that you are going to bring out Messrs.

a Beckett and Stanford’s Savonarola, an English Opera (recently

so triumphantly successful at Hamburg) by an English Author and

an English Composer; and on its first appearance in its own native

land it is to be disguised in German !

I forget who your Stage-Manager is at Covent Garden, where the

action of the chorus is directed by classic rules. But he will, I am

sure, be delighted to hear that Mr. Augustus Harris has put such

life and motion into this English chorus and these English singers

(but specially the chorus, as the principals, excepting Mr. Ludwig,

probably know quite enough without being taught, and wisely keep

it to themselves), that, from first to last, the Canterbury Pilgrims

Avas performed as if it was a real Acting Drama—one of Messrs.

Pettitt and Harris’s, for example,—instead of “ only an Opera.”

The scenery, too, was all that you could.desire, and that is saying a

great deal, isn’t it ?

It seems to me—(but if you, my dear Mr. Gye, are gye-rating

between the New German and the Old Italian style, you will not have

made up your mind in time to agree with me)—that Mr. Stanford,

thorough Musician as he is, has been bitten by a Wagnerish-Meister-

singerish notion of what a Comic Opera ought to be, and has said to

himself, without mentioning it to his Librettist, who, of course,

couldn’t have prevented him, hut who could have suggested dramatic

points, “ I will not write what is popularly known as a ‘ tune,’ and

if I ever catch myself dropping into tune as Wegg did into poetry, I

shall smother it up with instrumentation, and endeavour to let it be

forgotten as quickly as possible. No ; if t ever drop into tune, 1

deserve to be ‘ dropped into ’ by the Critics afterwards.” Now, as

Mr. Stanford has consistently stuck to this principle, he cannot he

robbed by any other unprincipled tComposer, for there is_literally

“ nothing to take away with you.”

Here and there quaint tuneful bits spring up suddenly, but being

immediately suppressed as too lively, they are like John Leech’s1

long-haired Skye terrier which seemed to have neither head nor tail,

and neArer take the form and shape of what are technically called

“numbers.” Yet a Composer would do well to recollect that there

is “ Luck in odd numbers,” and let us have a few good ones. What

he may be in serious Opera we shall know on hearing Savonarola ;

but in dealing with the greater part of the dialogue, and most of

the situations of this Comedy-Opera, he is so hopelessly undramatic

as to suggest the idea that he has failed to appreciate the real

humour of the subject, and has gone in heavily,—very heavily,—

for exalting his musical science at the expense of Dramatic Art.

For a real success in Opera, no matter whether serious, comic,

eccentric, or bouffe, Author and Composer ought to work together as

one man; and their umpire in all cases of dispute should be the

Stage-Manager, who in this case is the Emperor Augustus Drurio-

lanus.

I am certain, my dear Mr. Gye, that this Opera will improve on

repetition, and by the time you produce it at Covent Garden

translated into choice Italian with an English re-translation [done by

the Gasman or the man who takes the coats and hats and lends out

opera-glasses], its music will be well known, and extracts from it 'will

have become highly popular. The extracts can be made, though at

first hearing this would seem a difficult task. But Mr. a Beckett

has written songs and Mr. Stanford has written excellent music to

them, only he won’t stop to hear yon say, “ There ! I like that,” but

hurries on to the next bar as if he wanted to catch a train of thought

that had got ahead of him.

I think you, my dear Mr. Gye, would highly appreciate the acting

of the Drury Lane Company, as, with the exception of Mr. Ludwig-

and two of the chorus, it is mostly of the Italian-Operatic school..

Indeed, Mr. Barrington Eoote makes Hal o’ the Cliepe a thorough

Italian rendering of the Spanish Barber Figaro. But that he speaks

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

217

LETTERS TO SOME PEOPLE

About Other People’s Business.

The Operatic Canterbury Pilgrims ; or, Medieval Excursionists, personally conducted by Mr. Carl Rosa.

My dear Mr. G-ye,

You’ve been too busy, of course, to attend to anything'

except the business at your Italian Warehouse, and therefore unable

to be present at Drury Lane, where, you will be rejoiced to hear,

the greatest-success has been achieved by an English Opera written

by au English Author and English Composer, and sung by real

English singers. The success, too, was chiefly due to the “ book ; ”

and this will seem strange to you, with only your experience of

libretti, done into English by anybody (generally speaking), for

which the Public do not care a rap except as a guide to the story,

otherwise obscure, and which is of no value to anybody except the

translator, the printer, the publisher, the officials in the house (who

never have change for a florin when the price of the book is eighteen-

pence), and perhaps the Manager, who may have retained some

interest in it. But of late years, at other houses which yon have

hadjio opportunity of visiting, all this has been changed. In eccen-

tric boujfes we have the Author named with the Composer,—nay,

before him, as is his place in point of time, though not of tune.

Where would the Operatic Composer be without the Author, whose

libretto inspires him ? What is the complaint one constantly hears

from Composers who are credited by their friends with capabilities

for Opera, but who have never yet got beyond ballads ? They say,

“Ah! I should like to do an Opera, if I could only get a good

1 book ’ ! ” Bless them, there are lots of good hooks about,—goody-

goody books, and a Magazine called Good Words (I believe) into the

bargain, but not the book to inspire the Operatic Composer. I

emphasise “ Operatic,” because obviously the Composers of Sympho-

nies, of instrumental quartettes, fantasias, songs without words, &c.,

&c., &c., are independent of a librettist, but not so the Operatic

Composer. His raison d'etre is the Dramatic Author, as the raison

d’etre of Singers and Musicians is the Composer. Where would

Singers be without “little songs for them to sing”? where the

Musicians without “ little tunes for them to play ” ? and where the

Manager ? And, as yon yourself would put it with admirable can-

dour, where would you be but for all these talented people, whose

services are at your disposition for a consideration ? And so the world

is on the elephant, and the elephant on the tortoise, and the tortoise—

what is he on ? Well, he has to rely on himself and stand upon his

own dignity.

It was a happy thought, this selection by Mr. Gilbert a Beckett

of the idea of utilising the Canterbury Pilgrims. I should imagine

that he hit oil the title first, and then was utterly knocked over by

tbe inspiration. The association between a Beckett and Canterbury

is of course obvious and natural. Then the next thing was to chaw

up Chaucer, and trust to his own ingenuity for a plot. Here he

has succeeded thoroughly, for the plot is nearly as good as that of

the Merry Wives of Windsor, to whose paunchy, weak, cunning,

fatuous, vain, humorous, and wicked old hero, Sir Christopher

Synge (Mr. Ludwig) bears a close resemblance in all but the fat

knight’s unwieldy size and in his bachelorhood. For Sir Christo-

pher, in order to “keep up the Christopher,” is married to a young

wife,—she is young as represented by Miss Marion Burton,—whose

name is Dame Margery, of whom Sir Christopher, on reconsidera-

tion, might have sung, had Mr. Staneord given him such a

chance as Mr. Hatton would have done, “What! marry young

Margery, No ! No ! No ! ’’—but there’s nothing so rollicking, so

jovial, so “ tuney-tuney ” as the ballad of Old Simon the Cel-

larer throughout the Opera.

And this reminds me that you are going to bring out Messrs.

a Beckett and Stanford’s Savonarola, an English Opera (recently

so triumphantly successful at Hamburg) by an English Author and

an English Composer; and on its first appearance in its own native

land it is to be disguised in German !

I forget who your Stage-Manager is at Covent Garden, where the

action of the chorus is directed by classic rules. But he will, I am

sure, be delighted to hear that Mr. Augustus Harris has put such

life and motion into this English chorus and these English singers

(but specially the chorus, as the principals, excepting Mr. Ludwig,

probably know quite enough without being taught, and wisely keep

it to themselves), that, from first to last, the Canterbury Pilgrims

Avas performed as if it was a real Acting Drama—one of Messrs.

Pettitt and Harris’s, for example,—instead of “ only an Opera.”

The scenery, too, was all that you could.desire, and that is saying a

great deal, isn’t it ?

It seems to me—(but if you, my dear Mr. Gye, are gye-rating

between the New German and the Old Italian style, you will not have

made up your mind in time to agree with me)—that Mr. Stanford,

thorough Musician as he is, has been bitten by a Wagnerish-Meister-

singerish notion of what a Comic Opera ought to be, and has said to

himself, without mentioning it to his Librettist, who, of course,

couldn’t have prevented him, hut who could have suggested dramatic

points, “ I will not write what is popularly known as a ‘ tune,’ and

if I ever catch myself dropping into tune as Wegg did into poetry, I

shall smother it up with instrumentation, and endeavour to let it be

forgotten as quickly as possible. No ; if t ever drop into tune, 1

deserve to be ‘ dropped into ’ by the Critics afterwards.” Now, as

Mr. Stanford has consistently stuck to this principle, he cannot he

robbed by any other unprincipled tComposer, for there is_literally

“ nothing to take away with you.”

Here and there quaint tuneful bits spring up suddenly, but being

immediately suppressed as too lively, they are like John Leech’s1

long-haired Skye terrier which seemed to have neither head nor tail,

and neArer take the form and shape of what are technically called

“numbers.” Yet a Composer would do well to recollect that there

is “ Luck in odd numbers,” and let us have a few good ones. What

he may be in serious Opera we shall know on hearing Savonarola ;

but in dealing with the greater part of the dialogue, and most of

the situations of this Comedy-Opera, he is so hopelessly undramatic

as to suggest the idea that he has failed to appreciate the real

humour of the subject, and has gone in heavily,—very heavily,—

for exalting his musical science at the expense of Dramatic Art.

For a real success in Opera, no matter whether serious, comic,

eccentric, or bouffe, Author and Composer ought to work together as

one man; and their umpire in all cases of dispute should be the

Stage-Manager, who in this case is the Emperor Augustus Drurio-

lanus.

I am certain, my dear Mr. Gye, that this Opera will improve on

repetition, and by the time you produce it at Covent Garden

translated into choice Italian with an English re-translation [done by

the Gasman or the man who takes the coats and hats and lends out

opera-glasses], its music will be well known, and extracts from it 'will

have become highly popular. The extracts can be made, though at

first hearing this would seem a difficult task. But Mr. a Beckett

has written songs and Mr. Stanford has written excellent music to

them, only he won’t stop to hear yon say, “ There ! I like that,” but

hurries on to the next bar as if he wanted to catch a train of thought

that had got ahead of him.

I think you, my dear Mr. Gye, would highly appreciate the acting

of the Drury Lane Company, as, with the exception of Mr. Ludwig-

and two of the chorus, it is mostly of the Italian-Operatic school..

Indeed, Mr. Barrington Eoote makes Hal o’ the Cliepe a thorough

Italian rendering of the Spanish Barber Figaro. But that he speaks